Bantry Bay in the First World War

Published in Features, Issue 6 (November/December 2015), Volume 23, World War IBEREHAVEN, CO. CORK—PERHAPS NOT THE KEY TO THE ATLANTIC NOR AN ‘IRISH GIBRALTAR’, BUT NOT A BACKWATER EITHER

By John Ware

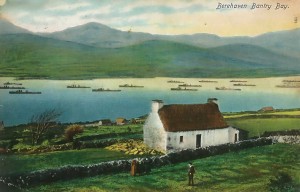

There is much about this picture that is typical of the Irish postcard. Even today, a century after this photograph was taken and coloured, you would not have to search long for a similar scene of a whitewashed thatched cottage with deep blue water behind it and the green hills rising in the background. The destroyer flotilla in the middle ground isn’t quite so typical these days, but in the early years of the twentieth century the might of the Royal Navy was something commonly seen in Irish waters. In the case of Berehaven, it was not just the odd destroyer force that briefly dropped anchor in Bantry Bay:

battleships, and indeed whole battle squadrons, were regular visitors, for these were home waters to the British Home Fleet, and the Atlantic was the exercise ground and playground of all the terrible great ships of which HMS Dreadnought was only the most famous. (Fergus O’Connor/Adrian Healy

The Royal Navy first moved into the waters of west Cork in 1797. The west coast of Ireland is, in sailorly terms, ‘iron-bound’, and the prevailing westerlies obliged ships to be wary of it. After all, the unhappy combination of rocks and the strong winds to drive ships onto those rocks had done for the Spanish Armada. But in 1796 the French had attempted to invade Ireland by way of Bantry Bay, and so the British were obliged to establish a base there in case they tried again. Here a naval base was little more than an anchorage with a modest shore establishment, all protected by some useful if unimposing fortification—in this case four Martello towers. With a large and expanding empire to police, Britain had naval bases all over the world, and Berehaven was thus in no way remarkable. Special or not, however, the base was modernised and strengthened at the end of the nineteenth century, as was the fleet, in response to the rising power of the French—and more particularly the German—navy. With the modern fortifications almost complete in September 1902, the Daily Mail (by way of the Kildare Observer) boasted about an ‘Irish Gibraltar’ and ‘the key of the Atlantic’; hyperbole aside, these were the glory days of Britain’s battle were the glory days of Britain’s battle fleets, and the west of Ireland was regularly dazzled by that glory.

The fleet

The Southern Star of 27 March 1909 reported that:

‘For eight days past, the mammoth battle ships Bellerophon, Lord Nelson, and Agamemnon have been manoeuvring in Bantry Bay, between the Roancarrig Light and Whiddy Island. The thunder of the big 12-inch guns can be heard at immense distances, and electric and searchlight displays may be witnessed at night from places far inland.’

Electric light? In Bantry Bay? And this 40 or 50 years before the ESB strung their power lines out this way? Magnificent!

A correspondent for the Galway Independent reflected in 1913, when the fleet dropped anchor in Galway Bay, that ‘it is curious to think that they carry more souls than the entire of our city holds’. Think, then, how Castletownbere, with a population of less than a thousand in 1914, would have faced the influx of such a fleet, given that the peacetime complement of one of the smaller, older battleships was somewhere in the region of 600 men. Well, what with sailors ashore being almost proverbially free with their money, there was much to be made for anyone selling anything, from bottled beer to rides in a jaunting car. For the quality, there was also the pleasant prospect of entertaining visitors from a higher and more Protestant society, with perhaps the further prospect of finding an eligible young lieutenant for a daughter to marry. The relatively isolated community of the Church of Ireland, after all, relied on regular infusions of new blood, which came most dependably from the armed forces, and west Cork—unlike, say, Cork City—was not army country.

British Navy warships at anchor in Berehaven, Co. Cork, c. 1914. (NLI)

The war

So the visitations of the fleet brought the wonders of electricity and the open hearts and pockets of a multitude of sailors to Bantry Bay. The fleet in its turn benefited from having a sheltered anchorage opening onto the North Atlantic which, in peacetime, provided both an ample training field and, as the Southern Star indicates, an extensive firing range. Ships like Agamemnon were already out of date when that 1909 article was written, and ships like the dreadnought Bellerophon were already being superseded, but when war broke out in August 1914 the battlecruiser HMS Tiger was at Berehaven undergoing gunnery trials in the open waters of the Atlantic. Had this newest and most fearsome vessel in the fleet been testing her guns in the English Channel it would not only have been a danger to the busy shipping lanes but might also, given the guns’ range of nearly fourteen miles, have constituted an act of war against France. Hence the utility of Berehaven.

Her gunnery trials hastily completed, Tiger left Bantry Bay for Scapa Flow in the Orkney Islands, where Britain’s battle fleet was concentrated for the war. Indeed, a survey of the provincial newspapers of the time time would seem to suggest that the Royal Navy departed from Irish waters for good, bag and baggage, but this turns out to be just a case of censorship at work. The navy had many more ships than were mustered at Scapa Flow, but of course none of them could be named in the papers, nor could their movements be reported. Yet the papers do provide clues to the continued naval presence in Berehaven, if in a rather less direct fashion. The Skibbereen Eagle of 15 January 1916 reported on a case brought before petty sessions, in which some local men were accused of ‘feloniously stealing and receiving quantities of coal and other articles the property of the government’. A ship like Tiger burned through something like 2,000 tons of coal in a busy week and, to accommodate such ships, the modernisation of the Bere Island facilities at the turn of the century had included the provision of a fuel dump with a capacity of half a million tons. When the war came, and shortages with it, 500,000 tons of His Majesty’s finest Welsh coal must have seemed a very tempting alternative to the damp turf that was all that was otherwise available.

A view of British Navy warships in Bantry Bay from St Michael’s Church, Bere Island. (NLI)

American sailors on shore leave in Berehaven in the winter of 1917. They have beer and female company, but it doesn’t quite match up to Havana or Manila! (Ralph Gifford)

The USS Utah in flames in the wake of the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbour in 1941. Also destroyed were the Oklahoma and Nevada. All three were stationed in Bantry Bay towards the end of the First World War.

The Americans

But besides these hints of the fleet’s presence and various mentions of U-boat activity in the area, the Berehaven base gets little enough notice in the records of the United Kingdom. The sea lanes to the south of Ireland were anything but quiet, being part of the western approaches to Britain and thus a vital conduit of war material, but it was Queenstown in Cork Harbour rather than the outlying Berehaven that provided the centre from which the British fought to keep these waters free of German submarines, and even then the more glamorous war, evidently more deserving of publicity, was being fought in the North Sea.

Berehaven looms large, however, in American accounts because it was in Irish waters that the United States were first committed to a European war. Within weeks of Woodrow Wilson’s declaration of war against Germany, a squadron of US destroyers steamed into Cork Harbour to take up the fight. Operating under overall British command, the American ships patrolled between Queenstown and Berehaven, and those first six destroyers were joined over the next year by many more, until there was a substantial fleet of destroyers, submarines, submarine chasers and even naval aircraft operating out of Cork Harbour and Bantry Bay, keeping the U-boats submerged and cautious, and ensuring that not a single US troop ship was lost on the transatlantic run.

The rapid build-up both of force and of naval infrastructure (in a short time they built not only a sizeable air base on Whiddy Island but also a baseball field at Castletownbere) was a bravura demonstration of American might and good old American know-how, but for the many thousands of US naval personnel south-west Ireland was hardly a dream posting. After one too many confrontations between moneyed sailors and jealous Corkmen, Cork City was declared out of bounds to the lower deck (even though the officers were pleased to enjoy the hospitality of Cork Yacht Club). That left for recreation the environs of Bantry Bay, but in the winter of 1917 the delights there were limited. Look at the picture of American sailors ashore. They have beer and female company, but the look on their faces shows that this place doesn’t quite match up to Havana or Manila.

It is quite possible that some of the sailors pictured came not from the destroyers or the little patrol boats but from the rather more substantial elements of the fleet. The United States committed no fewer than eight battleships to this war, and while five of them joined the Grand Fleet in Orkney, the other three—Utah, Oklahoma and Nevada—were assigned to Bantry Bay, in case elements of the German High Seas Fleet somehow broke out of the North Sea. Three ships might not seem like much, but battleships were the super-weapons of their time and the naval history of both world wars is filled with the alarms caused by the smallest numbers of enemy capital ships appearing where they were least wanted. Utah, Oklahoma and Nevada were major strategic assets. A generation after their stay in Ireland, these three battleships, along with the five others of the Pacific Fleet, were operating out of the Hawaiian base at Pearl Harbour, and when the Japanese thought to challenge the United States for mastery of the Pacific it was these ships that were targeted. It was that attack that spurred the Americans to fight their way across half of creation and to reduce much of Japan to ash when they got there. And here were some of those same ships at anchor in Bantry Bay, where the largest town in the vicinity isn’t even on a railway line any more.

John Ware is a part-time lecturer in military history in Adult Continuing Education, University College Cork.

Further reading

J.L. Leighton, Simsadus London: the American Navy in Europe (New York, 1920).

W.N. Still (ed.), The Queenstown Patrol: the diary of Commander Joseph Knefler Taussig, US Navy (Newport, 1996).