Attempting to reconcile the Red and the Green

Published in 20th-century / Contemporary History, Features, Issue 6 (November/December 2017), Volume 25Dr Patrick McCartan’s mission to Moscow, spring 1921.

By Michael Quinn

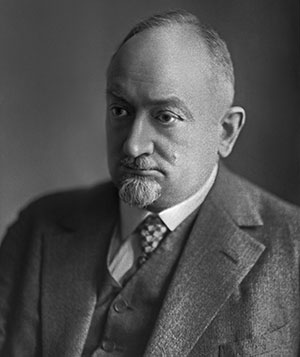

When Éamon de Valera, president of the First Dáil Éireann, boarded the SS Celtic bound for New York out of Liverpool in June 1919, his mission to the USA was twofold: to seek recognition for the Irish Republic from the US government and to raise a ‘war chest’ for the independence struggle. Already in America were Harry Boland, ‘Dev’s valet, shepherd, and manager’; Dr Patrick McCartan, the IRB’s clandestine envoy to Soviet Russia; and Liam Mellows, who would soon declare at an Irish Women’s Council meeting in New York that ‘[Soviet] Russia has given more encouragement to the Irish Republic than America had’.

Above (left to right): Harry Boland, Liam Mellows, Éamon de Valera, John Devoy (seated), Dr Patrick McCartan and Diarmuid Lynch on the roof of the Waldorf Hotel on 23 June 1919 shortly after de Valera’s arrival in the United States. Liam Mellows would soon declare that ‘[Soviet] Russia has given more encouragement to the Irish Republic than America had’. McCartan had already established a close relationship with Ludwig Martens of the US Soviet bureau. (UCD Archives)

But de Valera’s mission took on an added dimension when it became clear that in the American Zeitgeist the cause of Soviet Russia commanded considerable support. Soviet envoys were also in America seeking recognition, as well as trade connections. An informal embassy/Soviet bureau had been established in New York in early 1919 with a staff of 35. It was led by the German-Russian Ludwig Martens, who had been acquainted with Lenin since 1893 in the St Petersburg State Institute for Technology. With Martens was Santeri Nuorteva, a Finnish schoolteacher. Under threat of imprisonment for criticising the Czarist government, Nuorteva had been forced to leave for the US with his family in 1911. In spite of being formally illegal (the US had already enacted a boycott against Soviet Russia), the Soviet bureau established commercial contacts with more than a thousand American firms. Industry had been decimated in the Russian Civil War and the Soviets urgently sought machinery and railway stock. In exchange they offered gold and raw materials.

Above: Leader of the informal US Soviet bureau Ludwig Martens (right) and his assistant, Santeri Nuorteva. Nuorteva got out before the bureau was shut down in late 1920 and first received McCartan in Moscow in February 1921. Martens was deported on 22 January 1921. (Alamy)

Martens and Dr McCartan, in particular, formed a close collaboration that McCartan later described as being based upon ‘that sense of brotherhood which a common experience endured for a common purpose can alone induce’. By May 1920 a level of trust had been established between the Irish and the Soviets to the point where de Valera approved not only a loan of $20,000 to support the cash-strapped Soviet bureau (secured by some Czarist jewels) but also a draft treaty between the two embryonic states. The proposed treaty’s fifteen clauses incorporated pledges of mutual recognition before the nations of the world; active opposition to imperialistic exploitation and wars; pledges of religious tolerance and—remarkably—that the Irish Republic would be the accredited representative of the Roman Catholic Church within Soviet Russia; and mutual privileges for Irish–Soviet trade.

When de Valera finally accepted that official US recognition of the Irish Republic was not going to be granted by President Woodrow Wilson, he issued McCartan with the credentials to travel to Moscow to have the treaty ratified. He proposed that McCartan’s mission to Moscow should be expanded, and that formal Dáil Éireann procedures should be enacted to legitimise the initiative. He wrote to Arthur Griffith, the acting president of the Dáil during his absence in America:

‘Dr McCartan might be considered by you as a delegate from our government to Russia to ask for official recognition … I think he should be accompanied by at least two others—one representative of organised labour, for example [Cathal] O’Shannon, [Tom] Johnson, or [William] O’Brien, and one representative of industry and trade.’

With these recommendations to the Dáil it can be seen that de Valera was thinking ahead on Irish–Soviet trade relations, but also, as the leader of a nationalist movement, Sinn Féin, he recognised that the presence of additional delegates with left-wing convictions would strengthen Dr McCartan’s revolutionary credentials in the Soviet capital. In June 1920 the Dáil ratified the mission to Moscow by its adoption, on the proposal of Arthur Griffith, of the following motion: ‘That the ministry be authorised to dispatch a diplomatic mission to the government of the Russian Socialist Federal Soviet Republic with a view to establishing diplomatic relations’.

McCartan in Moscow

Above: People’s Commissar of Foreign Affairs Georgy Chicherin—in a meeting with McCartan on 17 February 1921 he quizzed him closely on reports that Irish republicans were hostile to communism. (ITAR-TASS/Alamy)

When McCartan reached Moscow he was soon informed that Soviet state officials were having second thoughts about ratifying the draft Irish–Soviet treaty. Following the defeat of British interventionist forces on the side of the White Russians, official Soviet government attitudes towards Britain had pragmatically changed. Anxious to normalise relations with industrialised powers to gain access to industrial goods for their war-torn economy, they were in the process of negotiating an Anglo-Soviet trade agreement. Santeri Nuorteva, with whom he had drawn up the draft treaty in the US less than a year previously, first received McCartan. Nuorteva, now a senior official with the Commissariat of Foreign Affairs (Narkomindel), confirmed that negotiations were under way with the British and that the Irish–Soviet position would have to ‘begin in the new and not on the basis of the proposed treaty’.

On 17 February 1921 McCartan had a second meeting, this time with Commissar G.V. Chicherin. Chicherin received McCartan politely but quizzed him closely on the possibility that President de Valera would accept Home Rule status for Ireland, on the Ulster question and on reports that Irish republicans were hostile to communism. He also enquired after the current status of the Irish Citizen Army. Chicherin invited McCartan to remain in Moscow, pending the outcome of the discussions with the British. It also seems that in his capacity as a representative of the IRB McCartan requested, in addition to the ratification of the treaty, the sale of munitions to the IRA. Such a request was not likely to impress Chicherin, who was hostile to Russian involvement with illegal political operations abroad. Accordingly, it came as no great surprise when an Anglo-Soviet trade agreement was signed in March 1921.

McCartan’s impressions of the Soviet state

McCartan discharged his final duty as the Irish representative to Russia with the submission of a memorandum on his impressions of the nascent Soviet state to the First Dáil. Displaying a strong sense of political scepticism and ideological opposition, the following extract best sums up his attitude to the new Soviet order:

‘Though it is claimed that the present government is dictatorship of the proletariat it is nothing of the kind. It is a dictatorship of the Communist Party, which represents less than one per cent of the population of Russia; and dictatorship of the Communist Party means in reality dictatorship of about half a dozen leaders of the Communist Party.’

And for McCartan’s interpretation of early Soviet attitudes towards Ireland:

‘There is some interest in Ireland on the part of those one meets, but the revolution in Ireland [was seen as] a national one and hence it was concluded had little or nothing in common with communism or the “world revolution” … There was some admiration for the fighting qualities of Irishmen but they were not communists and Irishmen everywhere are reactionaries, that is, they are not usually socialists … As a rule they [the Irish] are Catholics, and God and the churches are the opponents of communists. “Religion is the opiate of the workers” … the government of Russia would recognise the Republic of Ireland any day if they could do so without injuring Russia itself.’

With those words from a disappointed emissary the first period of Irish–Soviet diplomatic contacts was brought to an end. Dr McCartan arrived home from Moscow in late 1921 and, alone among those representatives who had served with de Valera in the US, gave his support to the Anglo-Irish Treaty. Despite this stance, he refused to take any kind of a job with the Free State government and tried to mediate between the two sides in the Civil War.

Yet there was one final gesture of generosity that Irish authorities extended to the Russian people in the revolutionary period, to alleviate the effects of famine and displacement that had arisen from the First World War and the Russian Civil War. The details were succinctly recorded in a Dáil report, signed by S. Ghabháin Uí Dhubhthaigh (George Gavan Duffy) and dated April 1922, just two months before the outbreak of the Civil War in Ireland:

‘A sum of £1,000 has been contributed, through the Saor an Leanbh [Save the Children] committee, towards the Irish effort for relief of the famine victims in Russia; this effort is attached to Dr Nansen’s admirable organisation in South Russia; unfortunately upwards of six million lives were lost before help arrived.’

What is noteworthy here is that the money was not sent directly to the Soviet government but rather through the offices of Fridtjof Nansen, the League of Nations’ first High Commissioner for Refugees. The decision to route the money through the League indicated the desire of the emerging Irish Free State government to be associated with the world body, as well as to distance itself from Soviet Russia and the emerging Soviet Union.

Conclusion

Above: Starving Russian children in October 1921. In April 1922 Dáil Éireann contributed £1,000 towards Russian famine relief—significantly not through the Soviet government but through the League of Nations Commission for Refugees. (Getty Images)

In spite of the unhappy outcome of McCartan’s mission to Moscow, relations between the Irish Republic and the Russian Soviet Federal Socialist Republic had began warmly in the revolutionary years of 1919–21, as is best demonstrated by the draft treaty of recognition. Yet even as the two sides united in a sense of anti-imperialism, constraining factors on the Irish side were evident. In the first instance de Valera and his delegation represented an emerging national democratic republic, in contrast to the Bolsheviks, who represented a state attempting to create the world’s first socialist entity. With the exception of the left-leaning Liam Mellows, the Irish were not drawn from or supportive of the labour or socialist movements. Nevertheless, de Valera did recognise the potential of the Russian revolution’s promise for self-determination for small nations, and the prospect that Soviet Russia might in the future influence developments throughout Europe along those lines. While McCartan expressed his unhappiness with de Valera’s cautious handling of the pursuit of an agreement with the Soviets in his publication With de Valera in America (1932), these complaints must also be seen in the light of McCartan’s subsequent distancing of himself from de Valera, commencing with his support for the Anglo-Irish Treaty.

Michael Quinn is the author of Irish–Soviet diplomatic and friendship relations, 1917–1991—special Russian Revolution centenary edition (Iontas Press, 2017).

FURTHER READING

D. Ferriter, Judging Dev: a reassessment of the life and legacy of Eamon de Valera (Dublin, 2007).

C. Desmond Greaves, Liam Mellows and the Irish Revolution (London, 1971).

P. McCartan, With de Valera in America (New York, 1932).

E. O’Connor, Reds and the Green: Ireland, Russia and the Communist Internationals (Dublin, 2004).

Read More:

The fates of Ludwig Martens and Santeri Nuorteva