ARTEFACTS: ‘Strongbow’s tomb’—nothing to deClare

Published in Artefacts, Issue 3 (May/June 2019), Volume 27By Stuart Kinsella

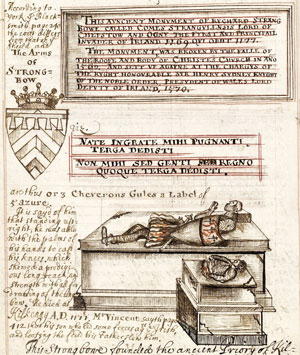

Above: Thomas Dingley’s c. 1680 drawing of the monument from his ‘Observations in a Voyage through the Kingdom of Ireland’. (NLI)

Strongbow, or Richard fitz Gilbert de Clare, was buried in 1176 in Christ Church Cathedral in Dublin ‘within sight of the hallowed cross’. So said Gerald of Wales, yet nothing is known of Strongbow’s tomb before it was damaged by the collapse of the cathedral’s south wall in 1562.

A nearby mural tablet recounts how Strongbow’s distant successor, Lord Deputy Sir Henry Sidney, had the monument ‘SET: VP: AGAYNE’ in 1570 (see p. ??). This was probably also when a smaller, half-sized monument was placed beside it, which Stanihurst identified, in a fantastical story, as that of Strongbow’s son, whom his father had cleft in twain for cowardice in battle. A Latin poem in brass affixed to the demi-figure lent some support. One translation ran:

‘O graceless son, who left thy sire

Amid the battle’s din;

And the same moment, turned thy back

On Country, Kith and Kin.’

Tellingly, Strongbow’s contemporary, Gerald, made no mention of this memorable tale, and the two recumbent effigies are unrelated. The larger figure dates from c. 1330, while the smaller—closer in style to a canopied female figure in the cathedral’s chapel of St Laurence O’Toole in the south transept—is probably late thirteenth- or early fourteenth-century. How the restoration took place is unclear, but in 1576 Sidney did pay £4 to ‘Sir Peter Lewys for Stranbowes tomb’. Lewis was not only steward of the lord deputy’s household but also a priest and precentor of Christ Church, where he supervised the cathedral’s rebuilding after the 1562 collapse. Around 1570 Lewis worked in Drogheda, which may corroborate Dudley Loftus’s (c. 1675) claim in his annals of Ireland that the tomb was removed from St Peter’s Church there, though the statement that it represents the earl of Desmond, beheaded in 1467, can hardly be true.

What is clear is that the present tomb replaced the original. The tomb’s shield is not that of the de Clare family and today remains unidentified. Sidney’s reputation as ‘skilled in antiquities’ endured, despite the assiduous, albeit misguided, researches of antiquaries and heralds in subsequent centuries.

Thomas Dingley on his 1680–1 visit to Ireland was one of the first to notice the inconsistency (pictured), but commentary on the monumental assemblage surrounding the tomb, even from James Ware, remained confused. It was probably Lyttleton in his 1767 study of Henry II who first brought some sobriety to the story of the slain son, observing that it was ‘hardly possible’ that no contemporary authors should have mentioned it.

As regards decoration, the mural tablet recording Sidney’s work was gilded for the arrival of a new lord lieutenant in 1697, while in the eighteenth century the tombs received such regular coats of whitewash that they appeared almost blue. Socially, the location was a focus for feeding the poor, witnessing legal and financial agreements and even bloodying the noses of new choristers. The last word, however, might go to Marc de Bombelles. In 1784 he described Strongbow’s tomb astutely as ‘the least authentic and the most remarkable’.

Stuart Kinsella’s doctoral thesis, from Trinity College Dublin, is on the architectural history of Christ Church Cathedral.