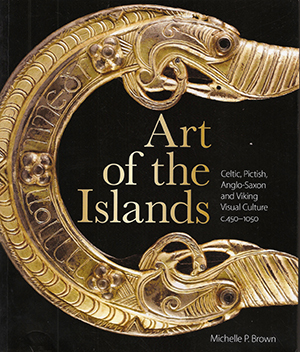

Art of the islands: Celtic, Pictish, Anglo-Saxon and Viking visual culture c. 450–1050

Published in Book Reviews, Book Reviews, Issue 6 (November/December 2016), Reviews, Volume 24MICHELLE P. BROWN

Bodleian Library

£25

ISBN 9781851244461

Reviewed by: Peter Harbison

The very first page of the Introduction of this book points out rightly that this is the first work to deal with the artistic development and cultural milieu of the whole ‘archipelago of islands’ comprising Britain and Ireland from the end of the Roman Empire to the Norman Conquest, and giving separate treatment to Ireland as well as to constituent parts of Britain—England, Scotland, Wales, Cornwall and the Isle of Man. The author admits that the vast amount of material to be discussed cannot all be treated in equal depth, but that does not prevent her from covering an incredible amount of ground at a very fast pace, as if bursting to share her huge enthusiasm and vast range of knowledge with an audience avid to read and listen. Celts, Picts, Britons, Anglo-Saxons and Vikings all make their appearance as contributing to the art of the period as practised in a variety of materials.

The very first page of the Introduction of this book points out rightly that this is the first work to deal with the artistic development and cultural milieu of the whole ‘archipelago of islands’ comprising Britain and Ireland from the end of the Roman Empire to the Norman Conquest, and giving separate treatment to Ireland as well as to constituent parts of Britain—England, Scotland, Wales, Cornwall and the Isle of Man. The author admits that the vast amount of material to be discussed cannot all be treated in equal depth, but that does not prevent her from covering an incredible amount of ground at a very fast pace, as if bursting to share her huge enthusiasm and vast range of knowledge with an audience avid to read and listen. Celts, Picts, Britons, Anglo-Saxons and Vikings all make their appearance as contributing to the art of the period as practised in a variety of materials.

Michelle P. Brown is arguably the most published expert on early medieval manuscripts, and her bibliography suggests that there is a lot more to come! It is not surprising, therefore, that she devotes more time to their ornamentation than to any other medium. But that is to the great advantage of the reader, who can learn so much about the latest thinking on manuscripts, their production and interaction with one another—and that is where Ireland gets its most extensive treatment for the Early Christian period, which Brown describes as ‘one of the most vibrant, innovative and intriguing phases of artistic development in Britain and Ireland’.

The Books of Durrow and Kells come in for particular attention, where she sees influences from the eastern Mediterranean and further afield—possible Armenian models for the St Matthew figure in Durrow, and the Coptic pose of the Virgin and Child in the Book of Kells. She writes imaginatively about Durrow, seeing its animal ornament as resembling ‘an elephant or a vacuum cleaner’! The Book of Kells she envisages as having been written on the Hebridean island of Iona, though with the possibility that it was completed at Kells, where it was stored for hundreds of years, though stolen and recovered not, as she thought, in the twelfth but in the eleventh century. In the Kells Codex she finds evidence of the disputed notion of multivalence—a variety of depths of meaning—in its various miniatures, including what she, and many others, call ‘The Arrest of Christ’ but which some scholars believe is ‘Christ on the Mount of Olives’, which is, as it were, what it says on the tin! The same identification she gives to the lowermost panel on the west face of Muiredach’s Cross at Monasterboice, which, however, is rather better explained as Roman soldiers mocking Christ as King of the Jews. More controversial is Brown’s suggestion that the Book of Kells was written by just one person—a fantastic achievement if true! The hand of Ferdomnach she sees around 807 not only in the Book of Armagh (which tells us so much about St Patrick) but also in the Book of MacDurnan, normally ascribed to an abbot of Armagh of that name who reigned in the late ninth/early tenth century. Much attention is devoted to English manuscripts, with the artistry of those from South Umbria getting special treatment, as does the Winchester School grouping, and Brown was cleverly able to discover the hands of two English scribes at work in St Catherine’s monastery on Mount Sinai.

In comparison to the manuscripts, metalwork and stonework are more summarily treated, with all of Ireland’s most famous first-millennium metalwork being dated to the eighth century, though a case could be made for placing at least some of them in the ninth. High crosses are mentioned too, and these she understands as developing in Northumbria and derived from those on Iona, which she sees as having been abandoned in 849. She suggests curiously that the Irish crosses received a new injection of inspiration from, among other things, ‘a Viking impetus towards renewed evangelism’, without much thought being given to any Carolingian contribution to the iconography.

For readers of History Ireland I have, perhaps unfairly, been concentrating on Ireland hitherto, but Brown’s coverage of British art of the first millennium and even beyond is much more extensive and thorough, though it must be said that she fortunately goes beyond her self-imposed end date of the Norman Conquest (of England) to include twelfth-century material from Ireland, while illustrating the White Island figures instead of the Dysert O’Dea Cross as fig. 96. Many items mentioned in the text are understandably not illustrated in a book of this size, and it may be noted that the quality of the pictures of stonework lags far behind those superb colour photos of manuscripts and metalwork—one of the finest of the latter being the silver-gilt piece in the St Ninian’s Isle hoard from Shetland adorning the front of the dust-jacket.

Any mild quibbles here are not designed to detract from the remarkable achievement of this book in covering mainly church but also lay artistic material of the period from 400 to almost 1200, which the author does in a remarkably fascinating style and depth, in a text which will best be understood by the knowledgeable expert and advanced student but which will also be of great benefit to the interested amateur.

Peter Harbison is Honorary Academic Editor with the Royal Irish Academy.