Almirante William Brown

Published in 18th–19th - Century History, Features, Issue 3 (Autumn 2001), Volume 9It is generally accepted throughout Argentina that that nation had two founding fathers: General San Martin, who led an army in an epic crossing of the Andes in 1817 to strike at the economic and political heart of Spanish colonial power in South America; and William Brown, a hitherto obscure Irish merchant sea captain. Brown’s improvised navy at Buenos Aires broke the Spanish blockade of the River Plate which threatened to strangle the newly founded rebel state, soon to call itself Argentina. Almost every town in Argentina, however small, has its statue of Almirante Brown, and a square, a street or an official building (sometimes all three) called after the Irishman.

Very little is known of the origins or the early years of this notable man. In Argentina he barely ever referred to them, and never in detail. It has been generally believed, both in Argentina and Ireland, that Brown was the son of a poor Irish peasant. This is highly unlikely. According to his own testimony, Brown was born in Foxford, County Mayo, in 1777. In the archives of the Genealogical Society at the Irish Club in London a George Browne is listed as a resident of the town in the same year. No other Browne or Brown, resident in Foxford in the 1770s, is recorded in any extant document. George Browne, a revenue collector, was related to the Westport Brownes, Marquesses of Sligo and Lords Altamont.

William Brown in admiral’s uniform.

Midshipman Brown

It seems likely, but cannot be proved, that George Browne had an illegitimate family in Foxford of which William was one. Admiral Lord Howe of the British navy, whose daughter became Lady Altamont, took an interest in young William and secured him a place in the British navy as a midshipman. That he was for a short time in that service is clear from family papers, and it is impossible to believe that William could have organised a successful navy out of a heterogeneous collection of ships and men without some kind of naval training.

At some stage in the 1790s William left the navy for the merchant service. It is fairly certain that he was mate on a British merchant ship, William, captured by the French corvette, Presidente, in 1801 and exchanged in 1802 for Lieutenant Crampon of the French frigate Resolue. (Crampon had been captured in Bantry Bay in December 1796 in Resolue’s longboat, now one of the exhibits at the National Maritime Museum, Dún Laoghaire.) On returning from France William resumed his career in the British merchant fleet, voyaging chiefly to the West Indies and eventually becoming master of a ship. He had in the meantime become intimate with the Chittys, a family of Channel pilots, master mariners and privateers in the Kentish port of Deal. In 1809 William married Eliza Chitty, and it was agreed that any daughters of the marriage would be brought up in Eliza’s religion (Anglican) and sons in William’s (Catholic). The pair were to undergo many hardships but their marriage seems to have been a close union.

William visited the River Plate region at least once before arriving to settle in 1811. He was probably attracted by reports of the region’s riches. Such riches had been brought to England by Rear Admiral Home-Popham in 1806.

On his own initiative he had sailed his Cape Town squadron across the South Atlantic on a virtually piratical expedition and seized Buenos Aires from Spain. In spite of the absence of help from Spain, the intruders were expelled by the local population, thus gaining the confidence to renounce Spanish rule in 1811.

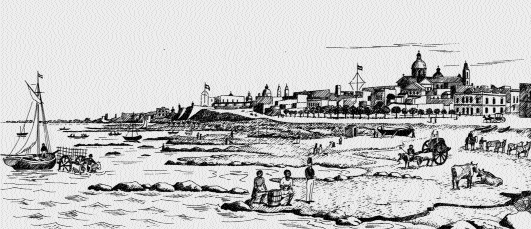

Hercules, a converted Russian merchant ship-flagship of Brown’s improvised navy in 1814.

Reluctant revolutionary

William arrived in his new homeland in 1811 in a captured French privateer Grand Napoleon renamed Eliza. His wife was to follow. His intention was to make a living trading out of Buenos Aires to Spanish and Portuguese colonial ports. William was a superb seaman, who quickly mastered the difficulties of navigating in the Plate with its innumerable treacherous shifting sand banks and its sudden perilous bursts of fierce winds, pamperos, off the interior of the South American continent. He developed regular sailings for the first time with Colonia on the Plate’s north bank, opposite Buenos Aires. (Now in Uruguay, Colonia was originally built by the Portuguese as an outlet from Brazil to the Plate.)

By the time of William’s arrival off Buenos Aires (where the Eliza was wrecked, but cargo saved, the proceeds of its sale enabling him to buy another ship) the people of the city and its hinterland had declared their independence. By now Spain had quite a strong naval squadron at Montevideo at the mouth of the Plate with a detachment based on Martin Garcia isle controlling the mouths of the Parana and Uruguay rivers. The maritime trade by which Buenos Aires lived was strangled at both ends of the Plate estuary. Brown continued to trade but was constantly harassed. He won a reputation as a formidable blockade runner. After the annihilation of a courageous but ramshackle first naval force assembled by the insurgents, Brown, already a hero to the populace of Buenos Aires, was asked to improvise a more effective insurgent navy and use his own naval experience to lead it in a decisive campaign to smash the blockade.

At first William refused, saying he had come to Buenos Aires to make a living as a peaceful mariner and trader and had been joined by his wife. In the end, however, his very sincere sympathy for the painfully suffering people of Buenos Aires (Portenos) and his own harsh treatment by the Spanish naval authorities led him to change his mind.

Early in 1814 William improvised a navy, with a big converted Russian merchant ship, renamed Hercules, as his flagship, and seamen from more than a dozen nations, a number of them Irish, to man it. In March he destroyed the Spaniards’ Martín García force and captured the strategic island. A few months later, in an action in which he displayed extraordinary tactical ability, he totally defeated the main Spanish squadron off Montevideo. A reinforcing army had already embarked in Spain but before it arrived this key to Spanish rule in south-east South America fell.

A new Drake?

Like Drake before him, William then went on a commerce-raiding expedition against the Spanish colonies on the Pacific coast. Rebellion was already rife but Spain’s naval power and wealth of merchant shipping seemed likely to maintain its rule there indefinitely. After a horrendous voyage down the coast of Tierra del Fuego and round Cape Horn, William played havoc with Spanish shipping, captured at different times Guayaquil and the strategic Galapagos Islands, and landed supplies and propaganda for the rebels against Spain, paving the way for their ultimate victory under San Martin in the south and Bolivar in the north. William had now become a legend, even capable of being in several places at the same time! Between September 1815 and January 1820, fourteen confident sightings of him are recorded in places hundreds of miles from where he actually was and arrangements for defences against him were made in places where he never proposed to go!

It was a battered Hercules with a weary crew that was nearing Montevideo early in 1816 when a ship warned him (falsely as it happened) that a powerful Portuguese squadron from Brazil was closing off Montevideo which a Portuguese army was besieging; he also believed Spanish ships were in the vicinity searching for Argentine privateers. He sailed on northward to seek surer information and Spanish shipping in the West Indies. After embarking essential supplies at Pernambuco, a centre of anti-Portuguese activity in northern Brazil, he fell in with a British warship, Brazen, which ordered him, a British subject commanding a privateer of a state not yet recognised by Britain, into Bridgetown, Barbados. William was hauled before a corrupt colonial court and Hercules, along with her valuable spoils from her many Spanish prizes, was seized. Eventually he made his way to London, and with the Chittys’ help appealed his Bridgetown sentence. In a long and complicated legal hearing he regained a portion of his prize but not his ship. Eliza joined him in London, having slipped out of Buenos Aires, in spite of a ban on her departure, thanks to the commander of the British frigate Amphion.

William now returned to Argentina to face another trial. He had sailed in 1815 for the Pacific in spite of a message from his political superiors forbidding him from doing so. William maintained that as commander of the Argentine navy he had the right to disregard it. The prosecution demanded a sentence of death, in vain, but the court decreed the confiscation of the remains of his Pacific campaign prize money (which ruined him), and his dismissal from the navy. William was so depressed at the outcome that he attempted suicide. But before long he was back in favour. He was still a popular hero in Buenos Aires and many leading public figures had stood by him. He regained his house, on the site of which today stands the Instituto Browniano on the Avenida Almirante Brown in the heart of Buenos Aires. He and his brother Michael quickly built up a thriving shipping business, exporting mules to the West Indies and returning with sugar, rum and other Antillean products. He also resuming his regular sailing to Colonia.

War with Brazil

Early in 1826 Argentina (as it began officially to call itself from 1825) got embroiled in a costly thirty-three-month war with the Empire of Brazil, now separated from Portugal and inheritor of a considerable portion of the very efficient Portuguese navy that had refused to return to Europe when Brazil became independent. In contrast Argentina’s navy had been reduced to a few gunboats. Reinstated in this hour of need, William had to improvise a real navy all over again.

He was up against far superior forces which had the advantage of bases in Uruguay (claimed by Brazil and by a strong political faction in Argentina). William managed to drive off a determined effort by the Brazilians to destroy the Argentine naval base at Los Pozos on the Plate in the western suburbs of Buenos Aires, a victory witnessed by great numbers of Portenos; he made a famous night raid on the Brazilian base at Montevideo; he evaded the Brazilian blockade and captured numerous Brazilian merchant ships, freeing all black slaves on board (Brazil did not abolish black slavery for another sixty years) and distributing republican propaganda all along the coast of Brazil from just south of Rio de Janeiro itself, the Brazilian capital, to Rio Grande do Sul. He won the most decisive victory of his career in February 1827 far up the Uruguay river off Juncal Island where the whole Brazilian river fleet was destroyed. On other occasions he tricked the Brazilians into grounding their vessels by his perfect knowledge of all the channels between the Plate’s intricate maze of sand banks. He constantly challenged the numerically far superior and very well commanded Brazilian squadron that kept as rigorous a blockade as possible at the mouth of the Plate. Eventually a peace was agreed in September 1828 by which both Brazil and Argentina recognised the independence of Uruguay.

Dictatorship

On 15 December 1828 William was appointed governor of Buenos Aires, the principal province in the Argentine republic. He immediately introduced a series of enlightened measures concerning public health, education and finance, but resigned in May 1829 when civil war broke out and the ambitious generals who provoked it refused his urgent plea to let the people themselves choose whom they wanted to govern them.

By the end of 1829 there emerged the notorious dictatorship of General Rosas, an arrogant, aggressive and cruel politician but a competent military man and, evidently in William’s eyes as well as those of many Argentinians, the only person capable of preventing the recently created Argentine republic from splitting up into a series of petty statelets.

Garibaldi

In the early years of Rosas’s rule William lived quietly in his Casa Amarilla, retaining his shipping interests and helping the highly practical Eliza who had established a small farm in the grounds round the house. By the late 1830s, however, Britain (which had already seized the Malvinas Islands in 1833), France and the United States, claiming that their interests in the River Plate area were threatened, sent warships there and in early 1841, after a number of provocative actions by all sides, Britain and France blockaded Argentina, based in ports in Uruguay, which also felt threatened by the Rosas regime. Uruguay, which had a small navy established by an Irish deserter from Popham’s expedition called Campbell, put the celebrated Italian seaman and patriot Garibaldi in charge of it and William, back in service for the third time, found himself at war with a formidable foe. Early in the conflict, before the British and French had begun to blockade the River Plate, Garibaldi sailed a squadron up the River Parana to cut off trade between Buenos Aires and the interior and to incite the inhabitants of the up-river provinces to revolt against Rosas. Off a small town called Costa Brava William defeated and largely destroyed Garibaldi’s squadron, though Garibaldi himself escaped (with William’s connivance, according to legend).

When the British and French navies intervened in force in the Plate estuary, Rosas ordered William to give up his blockade of Montevideo, which the Europeans began to use as a base. The Argentine squadron was on its way back to Buenos Aires on 22 July 1845 when the British and French admirals signalled to William that it was ‘detained’. William saw that resistance against two large segments of the two largest navies in the world would be suicidal, and anyway Rosas had sent strict orders to avoid any incident with the two big powers, so he reluctantly hauled down on each of his ships the flag ‘which during thirty-three years of continuing victories [he] had held high in full dignity in the waters of the Plate’.

Last years

William went home after this disaster and was not employed by Rosas again. He had been following with enthusiasm O’Connell’s agitation in Ireland for repeal of the Act of Union and had sent him financial support. When he heard of the horrors of the Famine he decided to visit his native land (he never, incidentally, took Argentine citizenship) and bring to Foxford what financial relief he could. He sailed from Buenos Aires in July 1847 but apart from that fact no record survives of this journey, save that he stayed at Liverpool with Rose Brennan, great-grand daughter of his sister Mary.

Guiseppe Garibaldi-Brown’s old enemy considered him to be the greatest naval leader of his time.

William Brown in his twilight years.

Rose had married a Protestant pastor called Leonard who put advertisements in Liverpool newspapers seeking other descendants of Mary; one or two turned up at Rose’s house but by then William had gone.

On the return voyage to Buenos Aires William disembarked at Montevideo and went to see his old enemy Garibaldi who is on record as considering him one of the greatest naval leaders of his time. The two became close friends. Back in Buenos Aires, William lived quietly, mixing chiefly with English residents in the Argentine capital and English seamen, naval as well as merchant, who put in there. In spite of his political differences with the Britain of the time, William was clearly no chauvinist.

William’s last known voyage was when the body of a General Alvear, another exile who had been prominent in the struggle against Spain, was brought home to be buried. William demanded and obtained the right to command the ship in which the remains of his old friend were being transported on the last stage of their voyage, which was from Montevideo to Buenos Aires through the great waterway which he knew so well and where he had achieved so much.

William died in 1857, aged eighty, when Buenos Aires was temporarily separated politically, in consequence of the long Rosas civil war, from the rest of Argentina. Both areas of divided Argentina went into mourning and Buenos Aires gave him a magnificent funeral, though Eliza, who survived him by some years, had to pay for his grave, which immediately became, and ever since has remained, a place of pilgrimage.

John de Courcy Ireland is a maritime historian and Honorary Research Officer of the Maritime Institute of Ireland.

Further reading:

J. de Courcy Ireland, The Admiral from Mayo: a life of Almirante William Brown of Foxford, father of the Argentine navy (Dublin 1995).