Alexius Stafford

Published in Early Modern History (1500–1700), Features, Issue 3 (Autumn 2000), Volume 8

James II-with his succession to the throne in 1685, the expectations of Catholics in Ireland rose considerably. (National Portrait Gallery)

The Ireland in which Alexius Stafford was born and reared, in the mid-1600s, was a troubled land. The great rebellion of 1641 had been followed by the advent of Oliver Cromwell and his subsequent land confiscations and plantations in the early 1650s. Battles, sieges, despoliation and depression had ravaged town and country. By 1688-89, there had been some recovery and many Catholic families like Stafford’s—probably of south Wexford Norman ancestry and possibly a dispossessed one—had survived through those turbulent times and re-emerged to renew the struggle for their rights.

Stafford’s background

Although one historian has said Alexius Stafford was a native of Bannow, County Wexford, it is more likely that he was a member of a branch of the Ballymacane Stafford family which, when their lands were confiscated, went into commerce in Wexford town. At any rate his family was apparently wealthy enough to send him abroad for his education as a priest.

Catholic church records show that he was a student at St Patrick’s Irish College in Lisbon and received first tonsure and minor orders on 29 June 1671. He was raised to the sub-deaconate on 26 July 1675, the deaconate on 4 August and ordained to the priesthood on 10 August of the same year. On his return to Ireland he lived in Wexford town where he ministered under Luke Wadding, then parish priest (not to be confused with the Franciscan Luke Wadding [1588-1657] from Waterford). Passing references in Wadding’s ‘Notebook’ indicate a close personal relationship between the two. Wadding was also of Old English stock dispossessed by Cromwell, and possibly a neighbour in Forth and Bargy.

The ‘Notebook’ reveals that Wadding, later bishop of Ferns (1683-1691) left Stafford ‘a silver pyx gilt with gold’ and that Stafford in turn, in June 1683, sent Wadding, via one Thomas Esmonde in Bristol, ‘a pendula or cloke’. There is another reference to Stafford’s receiving in 1686 a gift of £5 from Bishop Wadding, per Luke Hore. The circumstances outlined suggest that at this time Stafford may have been in Dublin and that the exchange of gifts—or payment—was facilitated by friendly Wexford merchants or mariners. Indeed Stafford may well have been Wadding’s eyes and ears in the newly emergent Jacobite environment of Dublin from 1685 onwards.

Catholic revival

By this time the political situation in Ireland and England had changed utterly. With the succession of the Catholic James Stuart, Duke of York, to the English throne in 1685, the expectations of Catholics in Ireland of some improvement in their lot rose considerably. James intimated that he planned some ameliorative measures, including the placing of Catholics on a footing of, at least, equality with members of the established church, in both England and Ireland.

In line with this policy James began to put Catholics in positions of power in Ireland. He appointed Richard Talbot, younger brother of Peter Talbot, Archbishop of Dublin, who had died in prison, as lieutenant general of the Irish army, later conferred on him the title of Earl of Tyrconnell and (in 1687) appointed him Lord Lieutenant. Catholic officers were promoted in the army and, generally, there was a Catholic revival throughout the country at the time.

During James’s short reign the Catholic church in Ireland, which had operated clandestinely since the time of Cromwell, came into the open again. Churches were taken over—by 1690 twenty in the archdiocese of Dublin alone—and appointments made to deaneries and other positions. Roman records show that Alexius Stafford was appointed dean of Christ Church in August 1686, though he was not then in actual possession. Cathedral accounts reveal that the reformed church dean and chapter were still in occupation and would remain so until 1689.

The Glorious Revolution

In England events moved quickly. The question of an heir to the throne was the catalyst. James’s second wife, Mary of Modena, also a Catholic, bore him a son. The likelihood that the infant would be brought up a Catholic sealed James’s fate. A Protestant Convention appealed to James’s son-in-law, William of Orange, who arrived in England in November 1688. James fled to France. Back in Ireland Tyrconnell and the Catholic party invited James to come to Ireland from which, they pointed out, he could launch an expedition to Scotland and then England to regain his thrones. James eventually complied and arrived in Ireland on 12 March 1689, the first English king to visit Ireland for nearly three centuries. He reached Dublin on Palm Sunday, 24 March, and was received with pomp and ceremony. It was probably at this stage that he appointed Stafford, already rising in Jacobite ranks, as a chaplain to the Royal Regiment, the king’s own personal bodyguard.

This surely must be taken as another indication of Stafford’s standing in Jacobite circles in Dublin and of James’s high opinion of him. There were other indicators of Stafford’s pre-eminence in religious and civil circles. Described in a contemporary account as ‘the celebrated Doctor Alexius Stafford’, he held doctorates in civil and canon law and was a preacher to the King’s Inns. James not only made him a master in chancery but also ‘intruded’ him into the deanery of Christ Church. His impeccable credentials as a member of the Wexford Old English gentry undoubtedly helped when Tyrconnell cast around for candidates for his remodelled corporations and proposed new parliament.

Richard Talbot, Earl of Tyrconnel-promoted Catholic officers in the army. (National Portrait Gallery, London)

Christ Church’s silver gilt plate was hidden by Chancellor Michael Jephson and his vergers in the crypt to deny Catholics its use

The Patriot Parliament

Following his arrival in Dublin, James promptly convened this parliament on 7 May 1689. It met in the old Four Courts, once a priory, adjacent to Christ Church Cathedral. Among the 232 members of the House of Commons was Dr Stafford, one of two MPs for the borough of Bannow, County Wexford. The other was Francis Plowden, commissioner for the revenue, described as ‘an Englishman’, and later one of the three lord justices appointed by James to administer civil government in Ireland after the death of Tyrconnell in August 1691.

Tyrconnell’s remodelling of the charters of the corporations enabled Catholics to secure places in town councils and be selected as members of parliament. The Jacobite parliament, therefore, was overwhelmingly Catholic and Old English in its membership. This ‘Patriot Parliament’ (as Thomas Davis later described it) proceeded to enact the repeal of the acts of settlement and explanation, with the objective of restoring estates to their pre-1641 owners, both Irish and Old English. A bill of attainder (targeting Williamite supporters) was also passed but the parliament was prorogued on 20 July 1689 and never met again.

Alexius Stafford’s remains may be either in a mass grave on Aughrim’s field or in any one of several local graveyards.

During the Jacobite supremacy in Dublin, many Protestant churches were seized by Catholics and returned to use as their chapels. These included the Royal Hospital, Kilmainham and Dublin Castle. James, ever conscious of Protestant claims on his strict adherence to the rule of law, tried to prevent such seizures, but was often unsuccessful. In September 1689, while he was out of Dublin, Christ Church was taken over and consecrated to Catholic use, apparently on the grounds that it was traditionally the Chapel Royal, and James himself later attended Mass there.

Christ Church plate hidden

But before it was taken over, there occurred a strange sequence of events aimed at denying Catholics use of the church plate consisting of silver gilt chalices, patens, candlesticks, flagons and alms dishes. The chancellor of Christ Church, Michael Jephson, and his vergers concealed the plate in two chests and hid them in the crypt, beneath the coffin of a Jacobite prelate, Bishop Cartwright of Chester, who had accompanied King James to Ireland but who had died in April 1689. Some days later, on Saturday 26 October, Dean Alexius Stafford took over the cathedral and next day celebrated Mass there, using a wooden tabernacle and two iron candlesticks (still in the possession of the cathedral authorities). It was a noteworthy occasion, with a great procession from Dublin Castle and soldiers lining the streets.

For the next eight months Dean Stafford officiated at Christ Church. Other chapter posts were also filled and the names of Fathers Maguire, Leary, D’Arcy, Mahony, Grace, Reilly and Dr Pierce are found among clergy ministering there. Mass was celebrated regularly and the king himself sometimes attended, most notably ten days after the cathedral’s repossession, on his return from his abortive northern expeditions. During this period, the former chancellor Jephson attempted to oust Dean Stafford through a law suit. But James ‘refused to hear so much as a demurrer in the Popish Dean of Christ’s Church, Mr Stafford’s case’. (Archbishop King’s account).

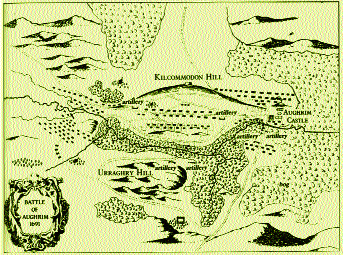

The Jacobite—and Catholic—resurgence in Dublin ended abruptly with the battle of the Boyne on 1 July 1690. James fled—as did his spiritual allies in Christ Church. His army made another stand at Aughrim on 12 July 1691 and it was there that the name of Alexius Stafford again entered the history books. Where he was and what he was doing in the interim is not known, though it is possible that he was with the Jacobite army as it fought at Limerick and Athlone.

He was certainly at Aughrim and it is a measure of his distinction that he is mentioned, by name and title, in at least two of the major Jacobite accounts of the battle—The Jacobite Narrative, originally entitled A light to the blind, and probably written by a Nicholas Plunkett of Fingal, and Poema de Hibernia, a contemporary poem in Latin about the event. Only the chief men on both sides are mentioned in these works.

Aughrim was fought on a Sunday and the many priests accompanying the Jacobite army celebrated Masses for the troops. They exhorted the men to give no quarter and assured them of a glorious victory. St Ruth, the Jacobite commander-in-chief, also addressed the army. When the battle commenced, the Royal Regiment was among the first units to charge the Williamites and at the head was Alexius Stafford. According to Poema de Hibernia, ‘He fell in front of the Royal Regiment as he was encouraging them upon the first charge’. James’s Regiment of Guards fought courageously and was even praised by a Williamite commander. The Jacobite Narrative, listing the Irish casualties, confirmed Stafford’s role and fate in the battle, calling him ‘an undaunted zealot, and a most pious churchman’. He was in there among the ‘flower of the Irish Army’ and aristocracy who included Lord Bourke, Viscount of Galway, and son of the Earl of Clanrickard, Brigadier Connell, Brigadier William Mansfield Barker, Brigadier Henry MacJohn O’Neill, Colonel Charles Moore, Colonel David Bourke, Colonel Ulick Bourke, Colonel Constantine MacGuire, Colonel James Talbot, Colonel Arthur, Colonel Mahony, Lieut.-Col. Morgan, Major Purcell, Sir John Everard and Colonel Felix O’Neill, all notables of Irish or English lineage.

Obviously Dr Alexius Stafford was no ordinary priest to be included in such distinguished company. He was, incidentally, but one of eighty priests killed at Aughrim, crucifixes in their hands, according to the Catholic Bishop of Cork. The day after the battle, the Williamites buried their own and some of the Irish dead on the battlefield itself; the rest they left unburied. It is recorded that many of these bodies were later buried in local graveyards. Thus, Alexius Stafford’s remains may be either in a mass grave on Aughrim’s field or in any one of several local graveyards.

Richard Roche is a local historian and writer.

Further reading:

J.G. Simms, Jacobite Ireland 1685-91 (London & Toronto 1969).

J.T. Gilbert, A Jacobite Narrative of the War in Ireland 1688-1691 (Dublin 1971).

T. Davis (ed. C. Gavan Duffy), The Patriot Parliament of 1689 (London 1893).

J.G. Simms, The Jacobite Parliament of 1689 (Dundalk 1966).