Ailtirí na hAiséirghe: Ireland’s fascist New Order

Published in 20th Century Social Perspectives, 20th-century / Contemporary History, Features, General, Issue 5 (Sep/Oct 2009), Volume 17

Gearóid Ó Cuinneagáin (left) leading a Craobh na hAiséirghe parade. While ostensibly a branch of Conradh na Gaeilge, Ó Cuinneagáin intended Craobh na hAiséirghe to be ‘a Hitler Youth Movement’. (Military Archives)

If anyone in Ireland is asked which side the country favoured in World War II, ‘The Allies, of course!’ will be the almost invariable reply. Ireland, after all, was Britain’s nearest neighbour. Tens of thousands served in the British armed forces; an even larger number earned their living in Britain’s war industries. The Irish government took a pro-Allied stance throughout the conflict, covertly assisting Britain and the United States in a variety of distinctly un-neutral ways. And the taoiseach of the day, Éamon de Valera, famously protested against the ‘cruel wrong’ done to Ireland’s fellow neutrals when they were invaded by Nazi Germany in 1940—even if, still more famously, he was to blot his copybook by condoling with Dublin’s German minister over the death of Adolf Hitler five years later.

Irish public opinion pro-Axis

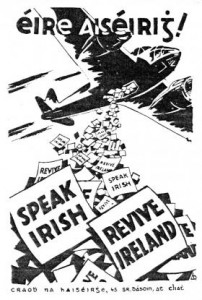

Craobh na hAiséirghe poster. (Military Archives)

When one asks with which of the two sides ordinary Irish people identified, however, the picture instantly becomes far murkier. Opinion-polling had yet to make its appearance on Irish shores, and censorship prevented expressions of support for either belligerent from appearing in the media. Yet at the time, a wide variety of well-informed observers placed on record their conviction that if the Irish people were forced to choose which camp to support in the war, the majority would have opted for the Axis rather than the Allies.

De Valera himself confided to an American journalist in July 1940 that ‘the people were pro-German’. The leader of the opposition, Richard Mulcahy, received a number of reports indicating that ‘mass opinion [is] setting pro-German’ the following year. American military intelligence was told the same thing by a ‘highly reliable’ member of the Oireachtas—most probably James Dillon—who lamented that ‘there was no anti-Nazism in Éire’. Looking north of the border, Freddie Boland of the Department of External Affairs found that ‘the vast majority of nationalists in the six-county area are absolutely pro-German’. And foreign diplomats, journalists and visitors were often startled by the evidence they found across Ireland of widespread pro-Axis sympathy, with ‘huge swastikas and anti-British symbols’ chalked or painted on walls and hoardings.

Considered in retrospect, though, this ought not to come as a surprise. Many people during the Emergency thought that Ireland owed Germany a debt for her support of the Easter Rising in 1916. Irish commentators often drew parallels between Germany’s ‘partition’ at Britain’s hands in the Treaty of Versailles and the division of their own country—Maud Gonne McBride was only one of a large number who regarded the Sudetenland as a Central European equivalent of the Six Counties. If the Axis won the war, many believed, Irish unity would soon follow. But over and above these considerations was a current of genuine enthusiasm for the achievements of the fascist states. In contrast to the depression-ridden, backward-looking democracies, Germany and Italy within a few years had revived their national cultures, recovered their ‘lost territories’ and put their millions of unemployed back to work. The lessons for Ireland seemed obvious. In a Europe in which, after the fall of France, democracy appeared fated to disappear, the Irish people needed to abandon their failed experiment with ‘nineteenth-century’ Westminster-style parliamentary government and look to the systems that seemed so successful on the Continent.

Gearóid Ó Cuinneagáin and Craobh na hAiséirghe

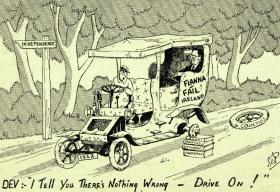

Aiséirghe cartoonist Seán Ó Riain comments on Irish democracy’s achievements. (Military Archives)

A young Belfast-born ex-civil servant, Gearóid Ó Cuinneagáin, had already arrived at this conclusion well before the war. In 1937 he published his first call for an alliance between Ireland and Mussolini’s Italy against their common enemy, Great Britain. During the first year of the Emergency he was a leading member of Ireland’s pro-Axis underground, working through a number of secretive subversive movements like Clann na Saoirse and the Irish Friends of Germany/Cumann Náisiúnta to prepare the ground for a German invasion. After most of his colleagues were interned in 1940, he struck out on his own and formed a branch of Conradh na Gaeilge to which he gave the name Craobh na hAiséirghe (‘Branch of the Resurrection’). Shielded by its association with the eminently respectable Gaelic League, Craobh na hAiséirghe was intended to be a ‘Hitler Youth Movement’ that would eventually take over Conradh itself and use it—as the Irish Republican Brotherhood had successfully done in the years before the Easter Rising—as a springboard to achieve its larger political objectives.

Craobh na hAiséirghe thrived during the early years of the Emergency, building up a network of sub-branches on both sides of the border and recruiting a nationwide membership of between 1,200 and 1,500. By no means were all of them fascist enthusiasts. Many would go on to highly prominent careers, including the future chief justice of the Supreme Court, Séamus Henchy; Liam Ó Laoghaire, head of the Irish Film Institute; and Pádraig Ó hUiginn, secretary of the Department of An Taoiseach and head of Bord Fáilte. Shortly after he joined Craobh na hAiséirghe, Ó hUiginn recalls having been carpeted by de Valera, ‘who asked me bluntly, “Is this a political organisation?” I assured him that it wasn’t.’

As time would show, Ó hUiginn’s initial estimation was far from accurate. Ó Cuinneagáin revealed his hand publicly in a speech early in 1942, when he denied that Craobh na hAiséirghe was trying merely

‘to gain the upper hand over Conradh na Gaeilge. We are sweating to gain the upper hand indeed, and soon—but the upper hand over all of Ireland! . . . Adolf Hitler said that he aimed to arrange the history of Europe for 1,000 years. But we Irish, it is fated for us to co-operate with arranging the affairs of the world for all eternity!’

This was not mere braggadocio. Ó Cuinneagáin truly did have global ambitions. Though he respected what Germany and Italy had achieved, he had no wish to become the local Irish representative of ‘the Hitler fan club’. On the contrary, he genuinely believed that a fascist Ireland could become more influential than its Continental counterparts—not militarily but ideologically. By narrowly basing their respective versions of fascism on ‘blood and soil’ and imperial conquest, Hitler and Mussolini could never hope to spread their systems to countries other than those they directly controlled. Ireland’s ‘twentieth-century destiny’, Ó Cuinneagáin maintained, was instead to become a model of the politics of the future for others to follow. By combining totalitarian efficiency with the universal values of Christianity, Ireland would be a laboratory for a wholly new ideology: a fascism designed for export. As a ‘missionary-ideological state’, spreading its doctrines overseas, Ireland could look forward to becoming ‘mistress of the Atlantic as it is the wish of Japan to become mistress of the Pacific. With the difference that we shall be masters in the Pacific Ocean also . . . Should we play our cards carefully and cleverly it will be possible for us from the capital of Ireland to dictate to the dictators themselves.’

Architects of the Resurrection

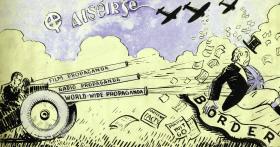

Aiséirghe proposed to build a massive conscript army to reconquer Northern Ireland. (Military Archives)

To this end—abandoning his effort to take over Conradh na Gaeilge from within, which turned out to be a harder nut to crack than he had imagined—Ó Cuinneagáin launched a new political party, Ailtirí na hAiséirghe (‘Architects of the Resurrection’), in June 1942. Its manifesto called for ‘the establishment of a state which, in the Christian perfection of its social and economic systems, will be a model for the whole world’. This was to be accomplished by the creation of a one-party system, with all power in the hands of a Ceannaire, or ‘Leader’, for a period of seven years in the first instance. Aiséirghe promised full employment to all citizens; an end to emigration (by the straightforward if draconian means of making it a criminal offence to leave the country); a massive state-directed economic expansion scheme; discrimination against Jews and freemasons; and the reconquest of Northern Ireland by the massive conscript army Ó Cuinneagáin proposed to build. Lastly, Irish would be restored as the national vernacular. Five years after the accession to power of an Aiséirghe régime, the use of the English language in public was to become unlawful.

The extremism of this programme by no means set Ailtirí na hAiséirghe outside the political pale. Attacks within ‘respectable’ circles on democracy as an ‘obsolete’ and ‘inefficient’ system were commonplace in 1930s Ireland; six months after Aiséirghe’s launch, a publication entitled National Action calling for the establishment of a Vichy-style authoritarian system in Ireland would sell well over 100,000 copies. Nor were Aiséirghe’s increasingly strident anti-Semitic diatribes unusual in a political atmosphere in which the leader of Clann na Talmhan, Michael Donnellan, boasted of the similarities between his political mission and that of Adolf Hitler, and in which the 1944 Fine Gael party congress listened to speeches describing Jewish refugees as ‘aliens fleeing from justice in Central Europe’ and complaining that it was ‘impossible to get Jews convicted in court’.

Influential patrons

A mass grave in Bergen-Belsen concentration camp shortly after liberation in April 1945. Aiséirghe had its greatest electoral success at the precise moment when such newsreel footage was being displayed on cinema screens across Ireland. In July 1945 Aiséirghe’s film-critic, described such footage as ‘hate-mongering’ fabrication. (wikimedia)

In such an environment Aiséirghe was able to make a level of progress that caused serious alarm to the British and US intelligence services. By 1945 it had approximately 60 branches on both sides of the border. It could also count on the assistance of several influential patrons. J. J. Walsh, a wealthy pro-Nazi who had been minister of posts and telegraphs in W. T. Cosgrave’s Cumann na nGaedheal administration in the 1920s, provided it with money and material support. Walsh’s ministerial colleague, Ernest Blythe, formerly a leading Blueshirt, joined Craobh na hAiséirghe, advised Ó Cuinneagáin on the drafting of Ailtirí na hAiséirghe’s constitution and gave the new party steadfast if occasionally critical backing in his widely circulated weekly journal, The Leader. The newly elected Oliver J. Flanagan declined an invitation to become Aiséirghe’s first TD but served the party as assiduously as though he were, providing Ó Cuinneagáin with an unlimited supply of blank parliamentary question forms to enable Aiséirghe to quiz the government in Flanagan’s name and intervening with ministers to secure permission for the launch of the party newspaper. And talented young people like Seán Treacy, who would end his career as Ceann Comhairle of Dáil Éireann, took their first steps in Irish politics as members and officials of the party.

It is significant that Aiséirghe had its greatest success shortly after the end of the war in Europe, at the precise moment when newsreel footage of the Nazi concentration camps were being displayed on cinema screens across Ireland. Aiséirghe had made no headway in the 1943 and 1944 general elections, partly because of Ó Cuinneagáin’s ambivalence over whether an anti-democratic party ought to participate at all in electoral politics. But in the local government elections of June 1945, the first to be held after the lifting of censorship, Aiséirghe took nine of the 26 seats it contested, topping the poll in two constituencies and gaining more than 11,000 first-preference votes. Its visibility may have been boosted by the lead it took in orchestrating the V-E Day riots in Dublin, which—contrary to popular legend—owed little or nothing to whatever minor part a youthful Charles J. Haughey may or may not have played in them. But the fact that so many Irish people had supported such a radical party, and that so many more would have done likewise if given the opportunity to vote for an Aiséirghe candidate in their area, excited much comment in Irish political circles.

Splits

Anti-semitism was a constant theme in Aiséirghe propaganda but was not a vote-loser in 1940s Ireland. (Military Archives)

Aiséirghe’s advance, however, was immediately to be followed by an even more striking reverse. Ó Cuinneagáin’s autocratic and abrasive leadership style produced conflicts with many of his subordinates—especially those, like the Aiséirghe national organiser, Tomás Ó Dochartaigh (a nephew of Cathal Brugha), who wanted to forge tactical alliances with sympathetic figures in the mainstream parties. Aiséirghe activists in Cork, where the movement was strongest, also were highly critical of what they saw as the Ceannaire’s incurable rhetorical incontinence and political immaturity. Fearing an attempt to ‘kick him upstairs’ to a figurehead position—something his erstwhile supporter Ernest Blythe was openly advocating in The Leader—Ó Cuinneagáin decided to get his retaliation in first. In September 1945 he suspended his leading critics, including Ó Dochartaigh, and succeeded in driving them out of the party the following month. The split had a devastating impact on Ailtirí na hAiséirghe, decimating its organisation and depriving it of its most talented officials. Ó Cuinneagáin’s Pyrrhic victory reversed the party’s fortunes at a stroke. Its momentum halted, Aiséirghe could afford no more self-inflicted wounds if it was to survive.

Ó Cuinneagáin proceeded to perpetrate one. Clann na Poblachta, a new republican party headed by the former IRA chief-of-staff Seán MacBride, was founded in July 1946. Aggrieved Aiséirghe officials protested that its radical economic and cultural programme borrowed freely from their own, discarding only the anti-democratic and anti-Semitic elements. Regardless of how much truth there may have been in these claims, Ó Cuinneagáin’s decision to dismiss Clann na Poblachta as a derivative ‘copycat’ movement unworthy of his attention was a disastrous one. Confronted with two overlapping parties, one of which was floundering under an incompetent leader and the other filled with dynamism and enthusiasm, Aiséirghe members and supporters defected to MacBride’s banner in large numbers. By 1950, when Ó Cuinneagáin expelled Aiséirghe’s last remaining elected representative for insubordination, MacBride had risen to become Ireland’s most high-profile politician. It is perhaps not too much to say that it was Aiséirghe’s failure to consolidate its position in 1945 as the radical alternative to the mainstream parties that made it possible for him to do so.

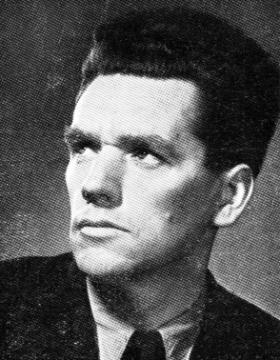

Tomás Ó Dochartaigh, Aiséirghe’s national organiser, who wanted to forge tactical alliances with sympathetic figures in the mainstream parties, was expelled from the party in October 1945. (Military Archives)

Even under the best possible circumstances, Ailtirí na hAiséirghe could never have achieved its goal of securing a monopoly of political power in Ireland. Had the Nazis won the war, they would have found little use for so prickly and intractable a personality as Gearóid Ó Cuinneagáin. But under a more flexible and pragmatic leader, Aiséirghe might well have evolved into a radical-right party like the Alleanza Nazionale, and played as important a role in Irish political life as Gianfranco Fini’s movement has done in Italy. That an openly pro-Axis, racist and totalitarian party could not only have made the progress it did but attract so much support from supposedly ‘respectable’ allies, however, says a good deal about the degree of alienation from which the independent Irish state continued to suffer more than two decades after the Civil War came to an end. It also suggests that many of the comforting myths with which the Emergency continues to be surrounded in Irish popular memory are long overdue for re-evaluation. HI

R. M. Douglas is Associate Professor of History at Colgate University, New York.

Further reading:

R. M. Douglas, ‘The pro-Axis underground in Ireland, 1939–42’, Historical Journal 49 (4) (Winter, 2006).

R. M. Douglas, Architects of the Resurrection: Ailtirí na hAiséirghe and the Fascist ‘New Order’ in Ireland (Manchester, 2009).

P. Mac an Bheatha, Téid Focal le Gaoith (Dublin, 1967).