After the Flight: the Plantation of Ulster

Published in Early Modern History (1500–1700), Features, Issue 4 (Jul/Aug 2007), Plantation of Ireland, Volume 15

When the principal Ulster lords, together with almost 100 of their followers, fled the province in September 1607 they left behind a situation of some confusion. Among their own followers the removal of the focus of local loyalties and the administrators of everyday life created a sense of despondency, and even of betrayal. Some of the poets, such as Fear Flatha Ó Gnímh, saw the flight and its consequences as a punishment of God for the sins of the earls. As late as the 1630s, when the chronicler Mícheál Ó Cléirigh wrote an account of the flight in the Annals of the Four Masters, ambivalent feelings existed about the events of September 1607. Ó Cléirigh lamented the departure of the lords and their followers but blamed those who had conceived and executed the scheme (the earls themselves, presumably). In an echo of the arguments of the poets, Ó Cléirigh also claimed that it was God who had not permitted the lords to remain on their lands.

Dublin administration caught unawares

The native Irish were not the only ones thrown into confusion by the flight of the earls. The Dublin administration too was caught unawares. In the years after the surrender of O’Neill at Mellifont in 1603 it had evolved a strategy for the government of Ulster that depended on the cooperation of O’Neill and O’Donnell. What had been agreed at Mellifont was extraordinary. Two years earlier, in 1601, the earl of Essex had been executed for plotting against the queen, yet O’Neill and O’Donnell, who had been in actual rebellion, were pardoned, restored to their lands and, in the case of O’Donnell, elevated to the peerage. The government hoped that they could transform the Ulster lords from powerful local chiefs into English-style landlords who would undertake the duties of representatives of the Dublin government in the localities, as had happened with their counterparts elsewhere. In this they failed. O’Neill, in particular, became increasingly restive with the restrictions being placed on his local authority by the appointment of Church of Ireland bishops within his jurisdiction and the efforts of former sub-lords to break free from his control using the mechanisms of the newly established common law courts.

As a result of the flight of the earls the Dublin administration, and King James I in London, faced the unexpected problem of how to govern Ulster at minimal cost. There was no shortage of advice. Those who had fought in the Elizabethan army during the Nine Years’ War had fully expected that the lands of the rebels would be confiscated and parcelled out among the victors.

![‘A project for the division and plantation of the escheated lands in six severall Counties of Ulster; Namelie Tirone, Colraine, Donnegall, Fermanagh, Ardmagh & Cavan: Concluded by his Ma[jes]ties Commissioners the 23rd of January 1608'. (Lambeth Palace Library)](/wp-content/uploads/2013/03/booktop.jpg)

‘A project for the division and plantation of the escheated lands in six severall Counties of Ulster; Namelie Tirone, Colraine, Donnegall, Fermanagh, Ardmagh & Cavan: Concluded by his Ma[jes]ties Commissioners the 23rd of January 1608′. (Lambeth Palace Library)

A project for the division…

‘A project for the division and plantation of the escheated lands in six severall Counties of Ulster; Namelie Tirone, Colraine, Donnegall, Fermanagh, Ardmagh & Cavan: Concluded by his Ma[jes]ties Commissioners the 23rd of January 1608′. (Lambeth Palace Library)

A tract of 1599 laid out a detailed plan to develop Ireland by colonisation following confiscation at the end of the war. In east Ulster, where Con O’Neill’s financial situation had forced him to sell much of his land to two speculators, James Hamilton and Hugh Montgomery, such colonisation was well under way by the time the earls left Ireland. The failure to confiscate the west Ulster land had caused considerable resentment among those who had fought in the war. One of these soldiers, Sir John Harrington, had ruefully written after the war that ‘I have lived to see that damnable rebel Tyrone brought to England, courteously received and well liked. O my lord, what is there doth not prove inconstancy of worldly matters’. By the time of the flight one of the most important of these former soldiers, Sir Arthur Chichester, had attained the most senior position in the government of Ireland, the lord deputyship, and his advice was clearly influential. He had acquired extensive lands in County Antrim and had established colonies of former soldiers there. Others had followed his example, and in Derry Sir Thomas Phillips had created a similar colony at Limavady. This idea of establishing colonies of former soldiers with some new settlers, the soldiers getting priority in the allocation of confiscated property, lay at the core of Chichester’s plan for Ulster in the wake of the flight.

‘One king, one allegiance and one law’

Chichester’s plan was not the only advice that the king was offered, however. Some who had been involved in previous plantations, such as Richard Spert, who had been a Munster settler in the 1580s, drew up proposals that they sent to the king. John Bell, the vicar of Christ Church in London, drew up a scheme to solve both the problem of governing Ulster and that of the poor in England by proposing that English vagrants be transported to Ireland. Neither of these schemes had much effect on decision-making. More important was the advice offered by the Irish attorney-general, Sir John Davies, who set out his analysis of the Irish situation in a book published in 1612 entitled A discovery of the true causes why Ireland was never entirely subdued until the beginning of his majesty’s happy reign. Unlike some contemporaries, Davies took the view that the native Irish world could be reformed and that the Nine Years’ War had laid the groundwork for this process. He argued that the Anglo-Norman settlement had failed because of the mistakes of government in not extending the full rights of the common law to the Irish and allowing the settlers to build up palatinate lordships outside royal control. These problems could now be solved by learning from the mistakes of the past. Thus war would never be at an end until there was ‘one king, one allegiance and one law’. A new society could only be built in Ulster within a common law framework. Davies optimistically predicted that the settlement of Ulster would be ‘a mixt plantation of British and Irish, that they might grow up together in one nation . . . with the blessing of God…. it will secure the peace of Ireland, assure it to the crown of England forever and finally make it a civil, and rich, a mighty and a flourishing kingdom’.

Events moved quickly amid all this theorising. The crown escheated, or confiscated, the lands of the earls, declaring them to have laid down their loyalty to the king by leaving the kingdom without his permission. In 1608 the local rising of Sir Cahir O’Doherty in Derry allowed the crown to extend the amount of land that it brought under its control. As a result, six of the nine counties of the historic province of Ulster—Armagh, Cavan, Coleraine (later renamed Londonderry), Donegal, Fermanagh and Tyrone—passed into crown hands. Through 1608 the newly acquired lands were surveyed in preparation for a settlement, but as yet the form that settlement would take was vague.

How the settlement was to work became clear in early 1609 with the publication of the project and the orders and conditions of the plantation scheme. While these were revised slightly in the following year, the broad scheme remained the same. Most of the work was done in London by the Irish committee of the privy council, and the loss of their records for these years means that we can never be sure about the detail of the process. Based on the outcome, however, it seems that Davies rather than Chichester became the driving force behind the scheme. Chichester’s constituency, the former soldiers, or ‘servitors’, did not fare well in the final distribution of land, achieving only 13% of the allocated land, almost the smallest proportion of any group in the scheme. The publication of the plantation scheme provided fresh impetus to the project, and through 1609 a new mapped survey of Ulster was made by Sir Josias Bodley in preparation for the division of lands.

A ‘British’ project

The ‘undertakers’ became the mainstay of the plantation scheme. Equal numbers of Scottish and English gentry received lands on which they would plant settlers. It is difficult not to see the hand of the king in this decision. Henceforth the Scots and English were referred to in official documentation as ‘British’.

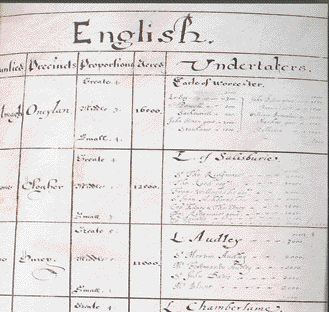

List of English undertakers. For example, in County (1st column) Fermanagh (5th row), in the precinct (2nd column) of Cloneally, land was divided in the proportion (3rd column) of 2 ‘great’ estates, 0 ‘middle’, and 1 ‘small’, totalling 5,000 acres (4th column). The undertaker (5th column) was the earl of Shrewsbury and land was held by Sir Edmund Bleuerhaseett (2,000 acres), Thomas Bleuerhaseett (2,000 acres) and Sir Hugh Woorrall (1,000 acres). (Lambeth Palace Library)

List of English undertakers…

List of English undertakers. For example, in County (1st column) Fermanagh (5th row), in the precinct (2nd column) of Cloneally, land was divided in the proportion (3rd column) of 2 ‘great’ estates, 0 ‘middle’, and 1 ‘small’, totalling 5,000 acres (4th column). The undertaker (5th column) was the earl of Shrewsbury and land was held by Sir Edmund Bleuerhaseett (2,000 acres), Thomas Bleuerhaseett (2,000 acres) and Sir Hugh Woorrall (1,000 acres). (Lambeth Palace Library)

This echoed the creation of Great Britain as a result of the union of the English and Scottish crowns in 1603 with the accession of James VI of Scotland to the English throne. It also provides the first hint that the Ulster plantation was not simply an exercise in land redistribution but an attempt to blend together different ethnic groups in Ulster to create a new society, as envisaged by Sir John Davies.

The government laid aside 40% of the land for these undertakers. It was divided into precincts, each one under the control of a chief undertaker. Each precinct was assigned to either English or Scots undertakers, many of whom harboured deep suspicions of the other. Estates were divided into three classes: 2,000 acres, 1,500 acres and 1,000 acres. These allocations were much smaller than those provided for in the sixteenth-century Munster plantation, reflecting the concern of the crown that undertakers should not become too powerful. As a result, much of Ulster became a land of small estates, contrasting sharply with the large estates of Hamilton, Montgomery and the earl of Antrim in east Ulster and the massive land banks of the earls of Clanricard, Cork and Ormond in other parts of the country. The scheme required undertakers to remove native Irish and introduce settlers onto their lands within two years, and to erect a castle on their holding before 1613. They were also enjoined to live together in villages, town creation being an important element of the scheme.

Four other groups also received land in the plantation scheme. Some 208 native freeholders acquired 14% of the escheated counties. Included here were some men who had remained loyal to the crown during the Nine Years’ War, but the majority were minor figures who had risen to prominence following the removal of the top social layer of Gaelic Ulster with the flight of the earls and their followers. Secondly, 57 precincts were allocated to servitors who were government officials or former soldiers. These men, unlike the undertakers, could employ native Irish as tenants. Thirdly, the established church acquired 18% of the confiscated land to support a Church of Ireland ministry that had barely been visible in Ulster before the plantation. Provision for clergy was one of the major challenges that the church faced in seventeenth-century Ireland since outside Ulster much of the church land and the right to present to livings had fallen into the hands of lay people, many of whom were Catholic. The provision of land for the church in Ulster under the plantation scheme provided a practical solution to a real problem. It was also a response to the problem of governing the province for, as one tract of 1599 noted, ‘a strange people governed by true religion and justice (the fruits of which are obedience and increase of wealth and prosperity) shall be evermore assured unto the prince’. Finally, as part of the reformation of Ulster 1% of land was assigned to support schools that would not only educate the sons of settlers but also inculcate the rudiments of civility into the sons of the surviving native élite. The provision for these ‘royal’ schools, although small, hinted at the planners’ concern to build shared social norms through education. A similar strategy of reform through education encouraged the sons of Old English and Irish lords to attend Trinity College, Dublin, as well as the University of Oxford.

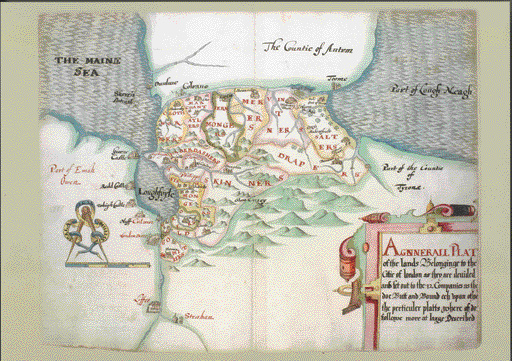

The crown excepted the county of Coleraine from these arrangements, assigning it to the city of London under the management of a new body called the Irish Society. This, like the Virginia Company established at the same time to settle parts of North America, was a joint stock company intended to attract London’s merchant wealth into the plantation scheme.

‘A General Plat of the Lands Belonging to the City of London as they are divided and set out . . .’ (Lambeth Palace Library)

Area Map…

‘A General Plat of the Lands Belonging to the City of London as they are divided and set out . . .’ (Lambeth Palace Library)

In 1613 the county, renamed Londonderry to reflect its new connection, was parcelled up into estates of about 3,000 acres each, divided among the twelve groups of London trade guilds. The Irish Society held the rebuilt ports of Derry and Coleraine, the main outlets for the economic products of the plantation and the main points of entry for settlers. These two towns were the economic successes of the plantation scheme, with populations of about 1,000 by 1630, making them about the same size as English market towns with a similar range of trades.

A coherent view of a new society

It is tempting to see the Ulster arrangements as simply part of a wider plantation policy being pursued in Ireland in the early seventeenth century. Plantations had already been initiated in Wicklow, Longford, Leitrim and west Offaly before the 1630s. Yet the Ulster scheme differed greatly to those implemented in other regions, involving more than simply landowning rearrangements, although that remained an integral part of the scheme. The Ulster scheme presented a unique, coherent blueprint for an evolving Ulster society. Thus it not only specified that settlers were to be introduced but also laid down the numbers of settlers who were to hold lands by particular types of tenure, stipulating the numbers of freeholders, leaseholders and tenants-at-will to be created on each estate. Thus the settlement set out an entirely new social structure, detailing the differing relationships of settlers to their landlord and, ultimately, the king. To draw a contemporary Scottish analogy, which may well have been in the mind of the king, the Ulster settlement was more like the arrangements for Highland society set out in the 1608 Statutes of Iona, which regulated social relationships, than the plantations of Lewis in 1597, 1605 and 1607, which did not.

The Ulster settlement went even further than this since it did not simply create new social relationships but also established a framework within which they would work. Estates were erected into manors with their own courts to resolve local disputes, market courts facilitated the growth of trade, and the structures of parish government, especially the vestry, provided a local government network. In addition, the normal machinery of common law, with its quarter sessions and assizes, provided places where people would meet and see the authority of the king manifest in legal proceedings. In this way local identities, in time, might overcome religious and ethnic animosities. Such courts and markets, in Sir John Davies’s vision, provided forums where the Scottish, English and Irish might grow into one nation through trade and law. There are even hints that by 1640 this might have been taking place. Ulster Catholics served as churchwardens in Church of Ireland parishes and they interacted with settlers at the various legal courts. The fact that Sir Phelim O’Neill forged a royal commission in 1641 suggests that many of the Ulster Irish were well acquainted with the trappings of royal government, such as seals and charters, by that date. The Ulster plantation scheme was as much about social engineering as it was about the redistribution of land.

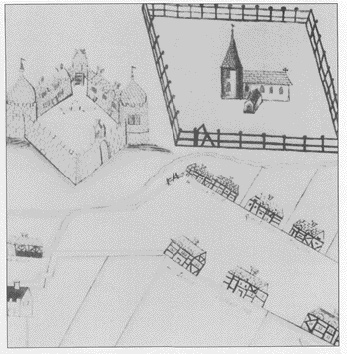

The Ulster plantation involved the foundation of new planned towns such as this one at Bellaghy, Co. Londonderry. (PRONI)

The Ulster plantation…

The Ulster plantation involved the foundation of new planned towns such as this one at Bellaghy, Co. Londonderry. (PRONI)

Sir Arthur Chichester…

Sir Arthur Chichester-acquired extensive lands in County Antrim and established colonies of former soldiers there in advance of the ‘official’ plantation.

Short-term failures

Yet for all these hints of the Ulster scheme’s progression, more substantial evidence exists that questions its effectiveness. Surveys of the plantation scheme in 1611, 1615, 1619 and 1622 brought reports of short-term failure and discontent among the settlers. The planners had left the implementation of their carefully articulated scheme in the hands of local landlords, who were presumed to have an interest in settling their estates. Most of those who were concerned to become undertakers were the least suited to carrying out the scheme, however. Some had fled from Scotland or England encumbered with debts. A few had religious reasons for going to Ireland, such as the Scottish Catholic earls of Abercorn and their followers in Strabane barony. Others sought rapid social advancement and hence did not have the required capital to invest in their lands. As Lord Deputy Chichester observed of the settlers, ‘those from England are, for the most part, plain country gentlemen . . . if they have any money they keep it close for hitherto they have disbursed little . . . The Scots come with greater part and better accompanied but it may be with less money in their purses’.

These financial difficulties meant that many undertakers failed to fulfil the terms of their grants. The 1619 plantation survey noted that 38 of the 164 estates had no castle, the best-endowed undertakers being the greatest offenders. Migration to Ulster fell far short of the intended level, and distant North America attracted many more settlers than Ireland did. By 1630 there may only have been about 16,000 Scottish settlers in Ulster, and rather fewer of English origin. Scottish migration to Ulster, mainly from western Scotland, was less than that to Poland and Scandinavia, the normal destination for those from the east coast of the kingdom. Many of those Ulster settlers clustered near ports, failing to venture far from their point of entry and leaving the remoter areas of the plantation almost untouched by settlement. As a result, Ulster undertakers kept native Irish tenants on their land, often paying substantial rents. This left newcomers open to the confiscation of their estates by the crown for breach of the conditions of the plantation. Hence a number of Ulster landowners associated themselves with the mainly Old English attempt to secure land tenure in the Graces of the late 1620s. Attempts to regulate the social structure of Ulster in the plantation scheme fell victim to the undertakers’ drive to optimise profit rather than to create social order.

The story is not an entirely negative one. By 1620 most of the major participants in the reorganisation of Ulster after the flight of the earls had departed the political stage. Hugh O’Neill, earl of Tyrone, died in Rome in 1616, Arthur Chichester left the Irish political stage in 1615, and Sir John Davies returned to England in 1619, dying shortly after. Yet the Ulster plantation scheme outlasted their deaths by over twenty years. What is remarkable is how little overt antagonism it created. By the 1630s settlers felt themselves sufficiently secure to begin building undefended houses with large windows. Arms and munitions were less common in the Ulster of the 1630s than they had been fifteen years earlier. What is perhaps most telling is that many of the organisers of the 1641 rising, including Sir Phelim O’Neill, Lord Maguire and various of the O’Reillys, had not lost land during the plantation scheme but instead benefited from plantation land grants.

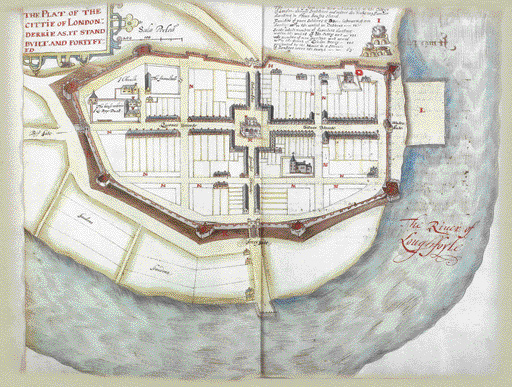

‘The Platt of the cittie of London Derrie as it stands built and fortyfyed’-one of the main outlets for the economic products of the plantation and the main points of entrance for settlers. (Lambeth Palace Library)

The Platt of the cittie of London Derrie…

‘The Platt of the cittie of London Derrie as it stands built and fortyfyed’-one of the main outlets for the economic products of the plantation and the main points of entrance for settlers. (Lambeth Palace Library)

All this points to the complex and contingent nature of the settlement of Ulster as it emerged in the decades after the flight of the earls. The distinctiveness of that scheme was born out of a desire on the part of the king and his councillors not simply to plant Ulster but to use the unique opportunity presented by the flight to establish social norms that might be emulated across the whole island. It was not simply about land redistribution, although a great deal of energy went into drafting plans for that. It aimed at creating a social framework, using the law, markets, schools and the church to establish an infrastructure for what can only be described as a significant piece of social engineering. While much of the settlement collapsed under the stresses of economic recession and war in the 1640s and had to be rebuilt in the 1660s, there were enduring features. The structure of estates and the peculiarity of the landholding features on those estates would contribute to the longer evolution of Ulster society. Again, the problems created by shortage of landlord capital and the long leases that resulted would not finally be resolved until the nineteenth century. All in all, the creation of a new society after the flight of the Ulster lords was a remarkable achievement, although one that failed to satisfy many contemporaries.

Raymond Gillespie is a professor of Irish history at NUI, Maynooth.

Further reading:

J.S. Curl, The Londonderry Plantation, 1609–1914 (Chichester, 1986).

R. Gillespie, Seventeenth-century Ireland (Dublin, 2006).

M. Perceval-Maxwell, The Scottish migration to Ulster in the reign of James I (London, 1973).

P. Robinson, The plantation of Ulster (Dublin, 1984).