(Ad)dressing Our Hidden Truths

Published in Issue 6 (November/December 2019), Reviews, Volume 27National Museum of Ireland, Collins Barracks (until May 2020)

By Brandi Goddard

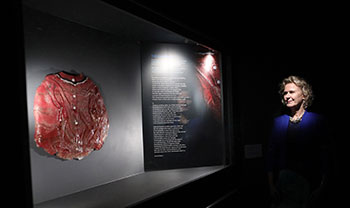

Above: Artist Alison Lowry explores issues of gender, institutional abuse and domestic violence—here with an installation of glass scissors and human hair.

In this striking exhibition, Alison Lowry, a Northern Irish artist, explores issues of gender, institutional abuse and domestic violence through the medium of glass objects and video. Lowry is clearly inspired and enraged by Ireland’s history of Magdalene laundries, industrial schools and mother-and-baby homes, and she masterfully crafts objects that are both beautiful and haunting and that reflect the widespread history of mistreatment and neglect of Irish women and children.

The exhibition space itself is darkened, winding and at times claustrophobic, all contributing to the solemn and contemplative atmosphere required of such a heavy subject. Relatively small in relation to the museum’s larger permanent exhibits, Lowry’s installation marks a departure from the standard museological pairing of physical artefact with historical narrative. As an undertaking of contemporary art, this exhibition would seem to fit more comfortably into one of the high-profile art galleries in Dublin, such as the Hugh Lane or IMMA. This choice of venue draws attention, however, to the history of museums as a colonial project, and more specifically the institutional linkages between Victorian-era centres of containment (laundries, schools and homes) and museological collecting practices. This museum, as a site for the decorative arts, invites comparisons with the history of women’s creative production, traditionally relegated to the meagre category of craft rather than perceived as equivalent to the ‘high arts’ of painting and sculpture. Lowry draws attention to this gendered division by elevating textiles to the level of sculpture through the manufacture of sartorial objects such as gowns and sweaters in the medium of glass. More importantly, the focus on textiles provides a formal allusion to the forced and unpaid work of women who laboured in the laundries and who created craft objects and embroideries that could be sold for profit by the institutions in which they were housed.

Above: Industrial school survivor and award-winning poet Connie Roberts, one of several women with whom Lowry collaborated.

Many of the delicate objects on display are beautifully crafted using the pâte de verre technique. Lowry has created a woman’s apron (the uniform of the women interned within the laundries) and several christening gowns (symbolic of the 796 babies fatally neglected at the Tuam mother-and-baby home) using a lost-wax method, which involves firing glass powders to create a lustrous and textured final product. The aforementioned christening gowns form the nucleus of the exhibition, both spatially and intellectually. Suspended from the ceiling in two separate rooms, nine glass gowns halt the viewer with a haunting sense of absence and mourning for the babies lost at Tuam, the names of whom are read aloud on an audio recording played on a loop in the space.

The shocking statistics of decades of female incarceration and infant deaths, along with the harrowing details of institutional abuse and neglect, are now within the public record and should be common knowledge. My own experience in the exhibition gallery, however, highlighted a larger societal issue at play in a nation still coming to terms with its own dark history: public apathy and judgement. The subject-matter of the exhibition represents a history still raw and unprocessed in the collective psyche. I was struck by the visceral experience of being in the space alongside others, but also shocked to witness the levity and dismissal exhibited by several fellow visitors. A large group with young children—including several adolescent girls—stormed the exhibition hall and treated the gallery space with more than a little disrespect. Speaking loudly, rushing to and fro, and deliberately knocking speaker pieces from their hooks on the wall were some aspects of the children’s behaviour, untempered by the adults in the group. What should have been a moment of contemplation, reflection and education instead became an exercise in wilful ignorance, blitheness and missed opportunities. Similarly, a cavalier dismissal by another woman, who commented ‘Is this all?’, exemplifies the public apathy with which these deep issues are often met.

Above: The cumbersome custom-made glass ‘slippers’, each of which weighs more than 5kg, worn by performance artist Jane Cherry in an agonising eight-minute video projection.

I found the most affective aspect of the exhibition to be the collaborative video piece made with performance artist Jane Cherry, herself a survivor of domestic violence. In an agonising eight-minute video projection, Cherry struggles to take 35 steps in cumbersome custom-made glass ‘slippers’, each of which weighs more than 5kg. This torturous physical act is symbolic of the heart-wrenching statistics discovered by Lowry and Cherry that, on average, an abused woman will suffer 35 separate instances of violence before seeking help. The real-life implications of these subjects are amplified by Lowry’s clear insistence on collaboration and solidarity with other women, including Cherry, award-winning poet and industrial school survivor Connie Roberts, glass artist Andrea Spencer and seamstress Ann Burrows. Historically speaking, female labour has been denigrated, and female sexuality deemed unnatural and sinful. By drawing attention to gendered discrimination, this exhibition engages with the still-ongoing struggles of Irish women, exemplified by seemingly unresolved debates on abortion, freshly minted domestic violence legislation, and high-profile cases of sexual assault and the vitriolic victim-blaming that is rampant on social media.

Alison Lowry is to be applauded for both her artistic mastery and her willingness to address, as her exhibition title states, the hidden truths of Ireland and the legacy of mother-and-baby homes and Magdalene laundries. The artist’s thoughtful creations, sensitivity to victims and survivors and encouragement of female collaboration reveal how art can be a paramountly constructive tool for tackling a subject at times too traumatic for words alone. What is needed now is more people who are willing to look closely at, and engage with, these hidden truths.

Brandi Goddard, a Ph.D student at the University of Alberta, researches the material culture and domestic lives of Irish women.