‘A stranger among us’: Edward Roth and the development of Telefís Éireann

Published in 20th-century / Contemporary History, Features, Issue 2 (March/April 2010), Volume 18

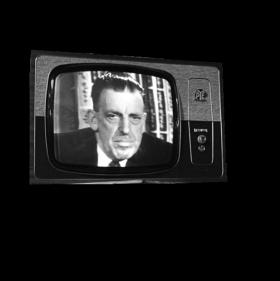

Taoiseach Seán Lemass speaking to the nation on the opening night of Telefís Éireann, New Year’s Eve 1961. At the first meeting of the new Television Authority in June 1960 his government placed them on notice that the financial stability of the new service was paramount and that any serious difficulty in this regard would place the independence of Telefís Éireann in jeopardy. (RTÉ Stills Library)

Ireland in the 1950s witnessed an often animated debate about television and how a native service should be structured and introduced to the nation. From the outset, looking to Britain and the United States, the state saw two models from which to choose. The first was a state-owned and state-financed public service, modelled on the BBC. This was an attractive, though costly, option, popular among those who advocated using the medium to provide high-quality educational material that would explore the complexities of Irish history and literature, support the Irish language, and generally reinforce what many regarded as a frail national culture.

The alternative was to follow the example of independent television in Britain and the commerical networks in the United States by granting a licence to a private firm. This option would not require government financing as television would be owned and operated by a corporation interested in making a profit by selling air time to advertisers. As a market-driven enterprise, it would seek the widest possible audience for its underwriters and would therefore feature predominantly imported popular American and British programmes. As a commerical enterprise, television would be designed to entertain viewers. For many this was the antithesis of public service broadcasting.

León Ó Broin influential

As the department responsible for broadcasting matters throughout the 1950s, Posts and Telegraphs attracted many proposals and queries concerning television throughout the decade. During this period the secretary of the department, León Ó Broin, was well placed to influence government policy and keenly interested in shaping the structure and form of Irish television. Ó Broin was a highly cultured man, a linguist who wrote history in his spare time and translated books from English into Irish for An Gúm, a state-funded publisher. Regarding the programmes broadcast by commercial networks in Britain and America with deep suspicion, Ó Broin considered the BBC as the best model for Irish television. He fully embraced the ‘Rethian’ philosophy of broadcasting that maintained that both radio and television should uplift and educate the nation and not simply provide popular entertainment for the masses.

Telefís Éireann’s first director-general, Edward Roth, President Éamon de Valera and the chairman of the Television Authority, Eamonn Andrews, on the opening night. (RTÉ Stills Library)

In the end a compromise was reached, engineered largely by Ó Broin. Telefís Éireann was established as a hybrid, a commerical public service charged with generating enough revenue to sustain itself through advertising while at the same time serving the nation as a public service. When the Television Authority was formally established in 1960, Ó Broin was troubled by the appointment of Eamonn Andrews as its chairman. Although the appointment of Andrews made sense to the Lemass government, he was hardly the Rethian intellectual Ó Broin would have preferred. Andrews had been an amateur boxer and sports commentator for Radio Éireann before enjoying tremendous success in British television by hosting popular entertainment programmes such as What’s My Line? and This is Your Life.

At the first meeting of the Television Authority (June 1960) the government minister responsible for overseeing the new service, Michael Hilliard, delivered a sharply worded address, much of which had been written, reviewed and edited by Taoiseach Seán Lemass. The government wanted the new service to become financially stable as quickly as possible, relating the achievement of this goal to the degree of independence that television would enjoy. There was no mistaking the threat of state intervention in his remarks. Here the commerical concerns of the new service far outweighed any public service expectation. The Lemass government placed the new authority on notice that the financial stability of the new service was paramount and that any serious difficulty in this regard would place the independence of Telefís Éireann in jeopardy.

The following month, the new Television Authority met to discuss filling the key position of Telefís Éireann’s director-general. This position was critical, as the director-general would be the executive charged with the complex task of staffing the service and getting Irish television off the ground and on the air. From the start, members of the authority realised that it would be difficult to find an Irish person with the requisite technical and managerial skills. Although they were reluctant even to consider hiring a non-national, the simple reality quickly became clear: there were no Irish candidates qualified for the position. In fact, the first round of applications was so weak that a decision was reluctantly made to extend the search. Just as things were beginning to look bleak, an application arrived from Guadalajara, Mexico, that stood head and shoulders above the rest. This came from from an American, Edward Roth, who was quickly invited to Dublin for an interview.

Roth the only serious candidate for DG

Festus Hagen (Ken Curtis) and Marshall Matt Dillon (James Arness) in Gunsmoke, one of countless ‘canned’ westerns purchased from American networks. (CBS)

One can see why Roth’s application impressed an authority under considerable pressure to find not only a candidate with very specific technical and managerial expertise but also one who understood the commercial component of television broadcasting. As an Irish-American Catholic, Roth had the ethnic and religious background to provide a certain level of comfort and cover for the Television Authority. Roth was born in Boston, Massachusetts, and both his maternal and paternal grandparents had emigrated from Ireland at the turn of the last century. He was educated at Boston and Columbia universities and spent a semester teaching at the University of Notre Dame, where he later returned to organise the university’s television station.

Roth joined the giant American network NBC in 1951 before moving to Paramount News, where he produced educational films. Before returning to NBC he spent two years working as programme manager for the WGN in Chicago, where he proved an able and adventurous manager and technician. In 1959 the network sent him to set up independent television stations first in Lima, Peru, and then in Monterrey and Guadalajara, Mexico. He was finishing his work in Guadalajara when he saw the position of director-general of Telefís Éireann advertised in a television trade journal.

Roth was interviewed by the Television Authority in August 1960 and made a remarkable impression. The chairman, Eamonn Andrews, wrote a report for the government explaining that the members were unanimous in their opinion that Roth should be hired. Significantly, Andrews understood that Roth was a product of American commercial television and, given the warnings he had received from the government, he understood that this was a critical component of Roth’s make-up. In his report Andrews emphasised that Roth did not come from a public service background, maintaining that this was an asset that would bring what he described as ‘an American viewpoint to balance our inevitably close association with . . . the BBC . . .’. Another element in Roth’s favour was his diplomatic skill; Andrews pointed out that he was impressed by his negotiations on delicate subjects with the Catholic hierarchy in South and Central America and with officials at the University of Notre Dame. Andrews admitted that Roth had little knowledge of Irish life but argued that his defects seemed to be considerably outweighed by his capacity to get the station on the air in the most economic and sensible way.

For Roth, TV primarily a medium of entertainment

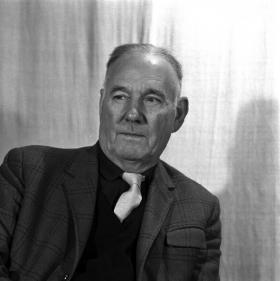

León Ó Broin, secretary of the Department of Posts and Telegraphs (pictured here in 1971), a formidable character who was deeply disturbed at the emphasis that Roth placed on television as primarily a source of entertainment. (RTÉ Stills Library)

Roth arrived in Dublin in November 1960, signed a contract and had his first formal meeting with the Television Authority. Afterwards the new director-general and Eamonn Andrews held a highly publicised press conference, which made headlines in all the Irish newspapers. Roth said all the right things and promised to deliver in one year a service that Irish citizens would be proud of. The honeymoon had begun; editorials in the Irish press expressed satisfaction that Roth had made a promising opening to his career and allayed many fears as to the direction the programmes would take. Other editorials were impressed by the sense of confidence exuded by the ‘handsome six-foot-four Bostonian’ and appreciated his general views on what an Irish service should be. Pictures of Ed Roth and his family appeared on the front page of all the major newspapers, which featured biographies and interviews with the new director-general.

From the outset, Roth made it clear that he had very specific ideas about television and what type of programmes should be broadcast. He clearly understood the government’s position, articulated quite forcefully on a number of occasions, that the service should not become a financial liability to the state and had to generate substantial income as quickly as possible. In interviews with the press one can detect Roth’s desire to feature popular programmes that would appeal to the widest possible audience and therefore attract advertisers and revenue for the station. Roth stressed his firm conviction that television was primarily a medium of entertainment. He often mentioned his fondness for westerns, and cautioned that at the outset the service would have to rely on a steady diet of foreign-made programmes. In its early days Telefís Éireann featured countless westerns; thus ‘cowboys and Indians’ became regular visitors in Irish homes, as the station cultivated a following that succeeded in delivering revenue to the fledgling service. Purchasing ‘canned’ American materialwas cheaper then developing indigenous programmes and, given the financial constraits of Telefís Éireann, the ‘public service’ component of Irish television languished.

By the spring of 1961 bumps in the road were creating difficulties for the director-general. Roth ran into problems on a number of fronts, especially from the secretary of the Department of Posts and Telegraphs, León Ó Broin. Ó Broin’s department was responsible for overseeing the new broadcasting service, though its powers to influence it were limited. The secretary was a formidable character and was deeply disturbed at the emphasis that Roth placed on television as primarily a source of entertainment. Much to the consternation of Roth and Eamonn Andrews, Ó Broin challenged the authority on a number of policy issues, even making direct inquiries into the content of programmes that were being scheduled for transmission.

Moves on

Edward Roth survived his two-year contract and succeeded in the daunting task of getting the service on the air. His run-ins with the language lobby, outraged cultural organisations, angry unions and myriad critics inside and outside of government are too numerous to detail here. Roth had hinted from early on that he would move on once the service was operational, and in September 1962 he announced that he would be leaving to take up a position as deputy managing director of Associated Television Ltd in London. He denied rumours that his departure was due to conflict with the government, the Television Authority or within Telefís Éireann itself. He was not above lashing out at critics, however, telling the press that ‘It sometimes appears that television criticism has replaced hurling as the national game’. Later he argued quite forcefully that the government should make substantial changes in the Broadcasting Act if Irish television was to prosper. He believed that the tension inherent in trying to run a commercial public service would prove debilitating, maintaining that public service broadcasting was simply antithetical to commercial TV.

When Roth first arrived in Dublin, he wrote to Seán O’Casey in an effort to gain the playwright’s permission to broadcast his plays on television. The two men met on a number of occasions and kept up a correspondence. O’Casey wrote to Roth when he heard that he was leaving and made reference to some of the battles and personalities who had challenged the director-general. Roth responded by thanking him for his support and admitting that, although he and his family had enjoyed Ireland, he would not want to repeat the experience. He confessed that after close to three years in Ireland he still could not understand the Irish. This prompted a sympathetic reply from the cantankerous O’Casey:

‘My dear Ed, you would be at least a demi-god if you understood the Irish, for they aren’t able to understand themselves, and worse still, they never try. Your advent was something of an invasion, reminding them of the Normans; . . . We are a muddled and a puzzled people, envious of one another, so how can a stranger be at peace among us?’

Roth freely admitted that mistakes had been made during his two years at Telefís Éireann. But he also maintained that the 1960 Broadcasting Act was highly problematic as it limited the options for the men and women who were responsible for Irish television. Many of his critics (and there were many) failed to appreciate the tension between public service and economic viability and the challenges that confronted the director-general and his staff. Understanding that this ‘hybrid’ structure restricted Irish television is critical to understanding the success and failures of Edward Roth and Irish television in general, not only in these early formative years but also today. HI

Robert Savage teaches history at Boston College, where he is co-director of the Irish Studies Program.

Further reading:

John Horgan, Broadcasting and public life, RTÉ and news and current affairs 1926–1997 (Dublin, 2004).

R.J. Savage Jr, A loss of innocence? Television and Irish society, 1960–1972(Manchester, 2010).