A precious bodily fluid—blood, the Irish connection

Published in Features, Issue 5 (September/October 2022), Volume 30By Shaun R. McCann

Above: Dr Norman Bethune with the Canadian Blood Transfusion Unit during the Spanish Civil War, one of those who perfected the logistics of providing blood transfusion on a large scale.

Blood is indeed a precious fluid that has intrigued man for millennia. Initially believed to contain the soul, memory or bravery, its place in Christian religion was preserved by the words of Christ at the Last Supper: ‘… after the same manner also He took the cup, when He supped saying, this cup is the New Testament in my blood; this do ye, as oft as ye drink it, in remembrance of me’. Over time, our understanding of blood has gone from the writings of Galen, largely based on the teachings of Hippocrates, of the four humours, (blood, yellow bile, black bile and phlegm), which held sway for 1,500 years until the Enlightenment led to a more nuanced understanding. St Augustine also contributed to the mystique when he said: ‘The soul … it is carried along to dwell in the blood’. Although William Harvey in the seventeenth century gets credit for his experiments and theory of the circulation, the Arab physician Ibn-al- Nafis described the circulation through the lungs in the thirteenth century, and the Chinese had described it as early as the second century BC.

During the Enlightenment, French and English physicians/scientists experimented with blood transfusion, concentrating on technical aspects and wrestling with the question: does blood contain some existential quality such as memory? Nobody seems to have asked the question if blood transfusion could be used to save lives. Although the issues of infection, clotting and blood groups were subsequently unravelled in the late nineteenth and early twentiethcentury, the logistics of providing blood transfusion on a large scale were not perfected until the Spanish Civil War (1936-39). Civilians were deliberately targeted during this conflict and two doctors, a Spaniard, Frederick Durán-Jordà, and a Canadian, Norman Bethune, are credited with organising mass blood transfusions for injured civilians and soldiers in Barcelona and Madrid respectively.

First bone marrow transplant in Ireland?

Where does Ireland fit into this story? It begins a long time ago. In the Táin Bó Cúailnge, the epic tale ofa cattle raid by the armies of Queen Medb and King Ailill to capture the great Brown Bull of Cooley, there is a passage that describes the first recorded bone marrow (the factory that makes blood) transplant in Ireland. It was technically a xenograft, that is, transplantation from an animal to a human:

‘Thereupon Fingin the prophetic leech asked of Cuchulain a vat of marrow wherewith to heal and to cure Ceithern son of Fintan. Cuchulain proceeded to the camp and entrenchment of the men of Erin, and whatsoever he found of herds and flocks and droves there he took away with him. And he made a marrow-mash of their flesh and their bones and their skins; and Cethern son of Fintan was placed in the marrow-bath till the end of three days and three nights and his flesh began to drink in the marrow-bath about him and the marrow-bath entered in within his stabs and his cuts, his sores and his many wounds. Thereafter he arose from the marrow-bath at the end of three days and three nights … It was thus Ceithern arose, with a slab of the chariot pressed to his belly so that his entrails and bowels would not drop out of him.’

On this account it appears as if the Irish were ahead of a twentieth-century innovation in medicine, bone marrow transplantation.

The idea that blood transfusion might be used to save lives, was beginning to germinate in the nineteenth century. Dr James Blundell, an English obstetrician, performed a human-to-human transfusion in 1818. Dr Robert McDonnell performed the first recorded blood transfusion in Ireland in 1870 and published his experience in the Dublin Quarterly Journal of Medical Science.

Above: Saint Augustine Taken to School by Saint Monica by Nicola di Pietro (1413/15). According to St Augustine ‘The soul … it is carried along to dwell in the blood’. (Pinoteca Vaticana)

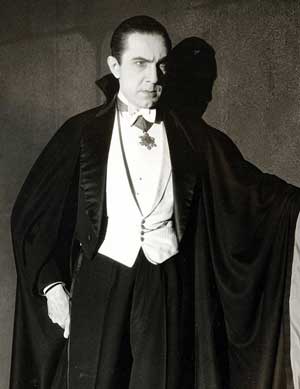

Bram Stoker’s Dracula

Another Irishman who made a somewhat unusual contribution to blood was Dubliner, Bram Stoker, whose book Dracula (1897) popularised the vampire legend. In Dracula, Stoker made some seminal observations about blood transfusion and some of which we would now consider to be rather antiquated. He clearly understood that repeated blood-letting, by Dracula on Lucy, could lead to severe anaemia and heart failure and that blood transfusion could be life-saving. Professor Van Helsing, who had been summoned to give advice, says, ‘there is no time to be lost. She will die for sheer want of blood to keep her heart’s action as it should be. There must be transfusion of blood at once.’ He also understood something about the technique of blood transfusion but knew nothing about blood groups, which were not clarified until the early 1900s. However, Van Helsing’s statement, ‘a brave man’s blood is the best thing on this earth when a woman is in trouble’, would certainly not be acceptable to-day, but does recall the ancient idea that blood contained special qualities.

Most of us take blood transfusion for granted and don’t consider the difficulties and problems that can be associated such a national service. Prior to the Second World War blood donors received a small payment but this ceased after the war and blood donation has remained a voluntary process in Ireland. This is also the case in the UK where the wonderful book by Richard Titmus in 1970, The Gift Relationship is said to have had a huge influence on the National Health Service there.

Guinness and blood transfusion

Since the beginning of the twentieth century, there has been a close relationship between the Guinness brewery and blood donation in Ireland. Dr (Sir) John Lumsden, chief medical officer at Guinness and founder of the St John Ambulance Brigade of Ireland in 1903, was largely responsible for the connection. He established an ‘on call’ blood donor panel to serve hospitals in the Dublin area, which later morphed into the National Blood Transfusion Association, established by Dr Noël Browne TD, Minister of Health, in 1948. The custom of giving the donor a glass of Guinness, as a token of appreciation, began with this historical association but is no longer acceptable and was discontinued in 2009. Apparently Good Friday was the busiest day at blood donation clinics in Ireland because it was the only place in Ireland where alcohol was available until the law was changed in 2018.

The relationship between the defence forces and blood transfusion in Ireland was very close. Dr Browne, in his book Against the Tide, describes how Seán MacBride’s wife was rushed to hospital and required a blood transfusion. Browne and Noel Hartnett visited a number of pubs to find a member of the defence forces to serve as a blood donor. They were successful and MacBride’s wife survived. Major P.J. McDonagh was the first organiser of the Blood Transfusion Association. All ranks acted as donors, from the latest recruits to the most senior levels. During The Emergency a functioning blood transfusion service was provided by the Defence Forces. St Bricin’s military hospital (named after St Bricin of Tomregan, who was a skilful surgeon in seventh-century Ireland) was used for the production of human serum in which blood was obtained, clotted, and the serum separated and collected for emergency use in sterilized milk bottles! This was due to the difficulty in obtaining technical glassware during the war.

Storage and transportation of blood changed dramatically when in 1950, two American doctors, Carl P. Walters and William P. Murphy Jr developed the plastic bag to replace glass bottles, which were expensive, unwieldly and heavy. Although plastic blood bags were widely tested during the Korean War, they were only introduced into the Irish Blood Transfusion Service (IBTS) in 1966 and in the NHS in 1970 and have facilitated the rapid, cheap, and safe transport of blood and blood products worldwide.

Besides blood being a life-saving fluid, are there any other ways it can be used? Yes. Although the eating of blood has been forbidden since Biblical days, blood as a source of protein was very important in nineteenth-century Ireland. In Knocknagashel, Co. Kerry, there is a local saying that ‘Kerry cows know Sunday’. This stemmed from the practice during the Great Famine of bleeding cows on Sundays for nourishment (protein) during the summer when they become fat on summer grass (I am grateful to Dr Peadar MacManais for bringing this information to my attention). A more benign way of eating blood, made from pig’s blood, fat and oatmeal, is black pudding, as part of the traditional Irish breakfast.

Above: The blood transfusion apparatus used by Dr Robert McDonnell in 1870, the first recorded in Ireland. (RCSI)

Blood-related diseases

Haemophilia, a disease that causes abnormal bleeding in males, was first described in Biblical times. Two major events shaped the treatment of this devastating ailment: the idea of preventive treatment (prophylactic administration of the missing blood clotting factor) and the manufacture of very large doses of the missing clotting factor, known as Factor VIII, by pharmaceutical companies. Although both of these initiatives had a huge beneficial impact on the quality of life for patients, unfortunately dark clouds were looming.

A strange disease appeared in the early 1980s, which inadvertently was to have a devastating effect on haemophiliac patients. Originally it was believed to be an immunological disorder of gay men, GRID (gay-related immune deficiency). It turned out to be a viral disease transmitted by sex, blood transfusion and the transfusion of concentrates of Factor VIII for patients with haemophilia. Ireland was no different to most countries and unfortunately many patients with haemophilia succumbed to this infection, now called Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome/Human Immunodeficiency Virus (AIDS/HIV). Happily, Factor VIII concentrates can be ‘inactivated’ (by destruction of the HIV virus) so that it is no longer transmissible. In addition, all donors in Ireland are tested for HIV viral infection (NAT testing, Nucleic Acid Testing, which detects the virus rather than the body’s reaction to infection) and for those unfortunate enough to contract HIV(AIDS), effective treatment is now available. Drs Luc Montagnier and Françiose Barré-Sinoussi were awarded the Nobel Prize for Medicine or Physiology for their discovery of the HIV (AIDS) virus in 2008.

Two other issues were to haunt the IBTS—the Hepatitis C crisis and ‘Mad Cow Disease’. The former caused morbidity and mortality and severely dented public trust in the IBTS and the second, happily, proved to be somewhat of a damp squib. Briefly, the Hepatitis crisis was unique to Ireland and East Germany. During the 1970s, the mechanism of a sometimes-fatal disease known as Haemolytic Disease of the New-born (HDNB) was unravelled. Rhesus negative mothers-to-be whose blood lacked the so-called Rhesus factor, and whose husband/partner was Rhesus positive, were in danger of making antibodies, which could cross the placenta and destroy the baby’s red cells on subsequent pregnancies. To prevent this, Rhesus negative women were offered vaccination with anti-D, which proved very effective at preventing HDNB. The anti-D vaccine was manufactured in Ireland by the BTSB and following vaccination, many Rhesus negative women became blood donors. It transpired that some batches of anti-D were infected with the Hepatitis C virus (discovered in 1990), so the virus entered the blood supply and unfortunately infected many people. Happily, anti-viral treatment is now available and blood donations are routinely tested for the virus.

Above: Bela Lugosi as Dracula in the 1931 film. In the original book author Bram Stoker Stoker made some seminal observations about blood transfusion. (Universal Studios)

As the Hepatitis C crisis began to wane, a new threat emerged, ‘Mad Cow Disease’. Cattle, which are natural herbivores, were given bonemeal instead of the more expensive soybean-derived protein as a cost-saving measure. The first case resulted in the death of an animal in the UK in 1986. They were suffering from bovine spongiform encephalopathy (BSE). The question arose, could Variant Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease (vCJD) (the human equivalent of BSE) be contracted by consuming meat from animals affected with BSE and more importantly, could vCJD be transmitted via blood and platelet transfusions? vCJD did not turn out to be a major hazard for blood transfusion services in Ireland, although people who lived in the UK when BSE in cattle was prevalent, were excluded from donating blood.

Ireland, like many countries, is suffering from the SARS-CoV-2 (COVID-19 coronavirus pandemic) but, unlike Hepatitis C and HIV, it is not transmitted via blood transfusion. There was a fear that donors might contract COVID-19 infection and thus the supply of blood might be reduced. However, an appointment system was introduced at donor clinics that secured an adequate supply of blood to Irish hospitals.

So, blood is a ‘precious bodily fluid’, which can save lives, occasionally be a carrier of disease, and can induce a myriad of emotional responses. However, in spite of all our scientific knowledge, the belief that blood contains some existential quality, continues to persist. The Vatican announced that a phial of blood from Pope John Paul II, would be available for veneration on the day of his beatification, 1 May 2011. Thus, it seems that non-scientific beliefs linger on but perhaps offer a degree of comfort to some. They are probably harmless, so long as they don’t impede scientific investigation.

Shaun R. McCann, Hon. FTCD, is Emeritus Professor of Haematology and Academic Medicine, St James’ Hospital and Trinity College, Dublin.

Further reading

D. Starr, An epic history of medicine and commerce (New York City, 1999).

S.R. McCann, A history of haematology: from Herodotus to HIV, (Oxford, 2016).

B. Stoker, Dracula, (London, 1897).