A hundred years in The Foggy Dew

Published in 18th–19th - Century History, 20th-century / Contemporary History, Features, Issue 1 (January/February 2019), Volume 27January 2019 marks the 100th anniversary of the Irish nationalist ballad The Foggy Dew. But who wrote it?

By Eugene Dunphy

Over the years a number of published works have attributed authorship of The Foggy Dew to a range of people. In 2004 the writer’s name was cited as ‘anonymous’. In 2005 his name was given as ‘Rev P. O’Neill’, and a book from 2015 notes that the song is sometimes attributed to ‘Peadar Kearney’. In fact, one of Ireland’s most enduring anthems was written by Fr Charles O’Neill and the blind musician Carl Gilbert Hardebeck.

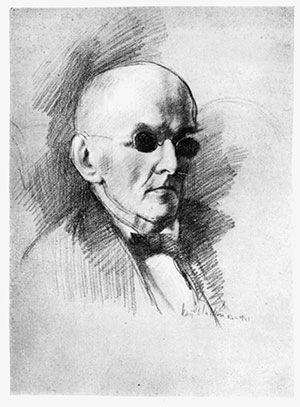

Above: A drawing of the ‘Blind Bard of Belfast’, Carl Gilbert Hardebeck, co-writer of The Foggy Dew, by Seán O’Sullivan RHA. (Capuchin Annual)

The men behind the anthem

Born on 20 September 1887 in Portglenone, Co. Antrim, Charles O’Neill attended his local primary school before furthering his education at St Malachy’s College, Belfast. On leaving St Malachy’s he studied for the priesthood in Maynooth. Ordained on 21 July 1912, he was appointed as curate to St Macartan’s Church, Loughinisland, Co. Down, and in 1915 as curate to St Mary’s Star of the Sea, Whitehouse, Belfast. As a dedicated member of the Gaelic League and the Gaelic Athletic Association, he devoted himself to the promotion of the Irish language, Gaelic football and hurling. Politically he supported Sinn Féin rather than Redmond’s Irish Parliamentary Party, which successfully persuaded many members of the Irish Volunteers (later the National Volunteers) to join the British army during the Great War of 1914–18. Believing that Redmond had duped them into joining under the pretence that Britain would grant Home Rule for Ireland, O’Neill’s loyalties lay with those breakaway Irish Volunteers who ignored Redmond’s call and chose instead to remain in Ireland to pursue self-government through armed insurrection. Séamus Ó Néill (1910–81), a writer and journalist who came to know ‘Fr Charlie’, spoke highly of the priest’s credentials: ‘He was a Sinn Féiner, a Gaelic Leaguer, a good Irish speaker and scholar; and I am using those words with meaning’.

In 1918 Fr O’Neill was seconded from Whitehouse to serve as curate at St Peter’s Cathedral in West Belfast. Here he met and befriended the blind London-born musician Carl Gilbert Hardebeck (1869–1945). It was a meeting of minds. Of a staunchly nationalist disposition, Hardebeck was a pianist, an Irish-speaker, a collector, arranger and teacher of traditional Gaelic songs, and resident organist at St Peter’s since 1904. He was also a friend of Patrick Pearse, Éamonn Ceannt and Joseph Mary Plunkett, all of whom were executed for playing leading roles in the Easter Rising of 1916. On Low Sunday, the first Sunday after the Rising, the usual St Peter’s Mass ended with an unusual performance by the blind organist in honour of those who had been executed. Pressing the keys and pulling out all the stops, he replaced the scheduled, sombre recessional hymn with a rousing rendition of the Peadar Kearney/Patrick Heaney collaboration Amhrán na bhFiann (‘The Soldier’s Song’). The execution of Pearse at Kilmainham Gaol on 3 May 1916 prompted Hardebeck to vocalise his trinity of beliefs: ‘I believe in God, Beethoven and Patrick Pearse!’

An anthem is born

On 21 January 1919 O’Neill attended the first meeting of Dáil Éireann at the Mansion House, Dublin. He listened despondently as the Speaker, Cathal Bruagha, read aloud a list of names of Irish men incarcerated in British jails. Éamon de Valera, who fought at Boland’s Mill during the Rising, was one of many names cited as being ‘imprisoned by foreigners’. When the Mansion House gathering agreed to adopt the principles of the Proclamation of the Irish Republic as outlined by Patrick Pearse and his comrades, despondency gave way to hope. Determined to commemorate those who had ‘died by Pearse’s side’, O’Neill used the melody and adapted the lyrics of an already published three-verse love-song, The Foggy Dew, which featured in Songs of the Irish Harpers. With words composed by E.H. Milligan and a traditional melody collected from a ‘Mr McGarvay of Dublin’, tenor John McCormack recorded this particular version in 1913:

Above: Fr Charles O’Neill—determined to commemorate those who had ‘died by Pearse’s side’, he used the melody and adapted the lyrics of an already published three-verse love-song, The Foggy Dew.

‘A-down the hill I went one morn a lovely maid I spied.

Her hair was bright as the dew that wets sweet Anner’s verdant side

“And where go ye sweet maid?” said I, she raised her eyes of blue,

And smiled and said “The boy I wed, I’m to meet him in the foggy dew”.’

Encapsulating the story of the six-day Rising in six verses, O’Neill imagined himself observing armed Irish Volunteers marching through central Dublin on Easter Monday morning, their regimented strides accompanied by the sullen toll of a nearby church bell. When the flag of the Irish Republic is hoisted on top of key buildings and the insurrection begins, he wishes that ‘our wild geese’ (the National Volunteers) fighting for ‘Albion’ against Germany on Turkish soil were in the city with Pearse, de Valera and the Irish Volunteers whose positions were being fired upon by the Helga from the River Liffey. While grieving for the ‘fearless men but few’ who died so that ‘freedom’s light might shine’, he also laments those who lost their lives in the service of the British army and navy.

Having added a modest piano accompaniment, O’Neill sent his completed song to the Dublin-based publishers Whelan & Co., stipulating that he wished to be referred to as ‘Iascaire’ (‘fisherman’) on the printed score—in honour of St Peter, ‘fisher of men’. It’s not surprising that he approached Whelan’s since the company had already published The Soldier’s Song by Peadar Kearney, The Watchword of Labour by James Connolly and Ireland All Over by Eamonn Ceannt. Priced at one shilling, O’Neill’s song was published in 1919, the cover simply stating: ‘The Foggy Dew. Words and Music by Iascaire.’ Soon after, Whelan’s released an amended edition with a more sophisticated piano arrangement. Priced at two shillings, the newly styled cover featured the following information: ‘The Foggy Dew. Old Irish Air. Words by Iascaire. Accompaniment by Carl G. Hardebeck.’ Including the musical direction andante mosso (‘increasing walking pace’), the pitch-perfect musician opened the song with nine block chords as if mimicking the tolling of an Angelus bell. With the common time pulse given as a slow 69 at the introduction and ascending to a quicker 92 at the first verse, he transformed O’Neill’s ballad into a Volunteer marching tune, an evergreen anthem:

Above: ‘These men, when released, spread the song through the length and breadth of the country’—IRA members detained at Ballykinlar internment camp, Co. Down, were frequently known to sing The Foggy Dew at ‘camp concerts’. This photo of the camp’s troupe may have been taken in late 1921/early 1922 at a concert in Dublin after their release.

‘As down the glen one Easter morn to a city fair rode I

There armed lines of marching men in squadrons passed me by

No pipes did hum, nor battle drum did sound its loud tattoo

But the Angelus bell o’er the Liffey’s swell rang out in the foggy dew.’

Sung all over

Eighteen-year-old Seamus O’Doherty, a singer from Venice Street in West Belfast, was the first to introduce the song to Belfast audiences, and by July 1920 the song ‘was being sung all over Antrim and Down’. In October of that year O’Doherty made his New York singing debut at the city’s Polo Grounds, where huge crowds gathered to hear a speech by de Valera. Singing The Foggy Dew without the aid of a microphone, he recalled that ‘every Irishman and his brother were in the city that day!’ By 1921 the song had become a favourite among the ranks of the Belfast IRA. Indeed, IRA members detained at Ballykinlar internment camp were frequently known to sing it at ‘camp concerts’. As the Redemptorist priest Fr Daniel Cummings recorded, ‘These men, when released, spread the song through the length and breadth of the country’. In November, clergy from all over Ireland gathered at Armagh’s St Patrick’s Cathedral to hear the inaugural ringing of the newly installed carillon of 39 bells. One of Belgium’s leading bellringers, Monsieur Nauwalaerts of Bruges, manipulated the sturdy ropes of the bells to ring out The Foggy Dew as well as pieces by Schubert and Beethoven. In late December 1921 the Irish-language publication Misneach published An Drúcht Céo, an Irish translation of all six verses of O’Neill’s song. Little is known of the translator’s identity except to say that he used the pen-name ‘Connla’. Shortly after, the Cavan newspaper The Anglo-Celt included sections of Connla’s An Drúcht Céo in its regular ‘teach yourself Irish’ columns:

‘Dul síos an gleann dom maidin Chásc’ ar chathair bhí mo thriall

Nuair casadh orm buíon Gael do sheas ’sa mbearna bhaoil

Níor sheinn píb fonn níor fhógair drum’ an chaismirt nó an gleo

Acht bhí ’n Fháilte go beog’ mar cheol ón gclog dá clos ins an Drúcht Ceo.’

In May 1928 the ‘weekly organ of republican opinion’, An Phoblacht, published yet another rendering, this time by Donegal-born Seosamh Ó Griana. What is noticeable about this translation is that de Valera’s name, which is mentioned in the fifth verse of O’Neill’s original text, is omitted—not surprising, since republicans such as Ó Griana believed that de Valera had turned his back on the republican cause.

1930s to 1960s

In January 1932 Hardebeck set up permanent residence in Dublin, where he and a number of Irish-language enthusiasts, such as the printer, publisher and former Irish Volunteer Colm Ó Lochlainn, attempted to establish a national school of traditional music where classes would be conducted through the medium of Irish. Interestingly, Ó Lochlainn’s father, John, was one of three partners in O’Loughlin, Murphy & Boland, printers of the first edition of The Foggy Dew. In 1938 Irish-American singer Jim Dwyer went into a New York recording studio and recorded the song.

Above: Fr O’Neill with Éamon de Valera, c. 1950s. Ironically, in May 1928 An Phoblacht published an Irish translation in which de Valera, mentioned in O’Neill’s original English text, is omitted.

Though it had firmly established itself as one of Ireland’s most popular anthems, there was a certain level of confusion concerning the identity of ‘Iascaire’. In 1945 the Tyrone-born writer and journalist Benedict Kiely was conversing with a priest in the reception area of a Belfast hotel. As they talked, O’Neill walked past, exited through the revolving foyer doors, stepped out onto the bustling Royal Avenue and proceeded on his busy way. ‘That was the man who wrote The Foggy Dew’, the priest informed the astonished Kiely, who later recalled the chance encounter: ‘Like many another, I had too easily assumed that splendid song of 1916 was anonymous … It was startling to think that one mind had moulded the words, that one hand had written them down.’ American civil rights activists such as Odetta Holmes could identify with the sentiments of the song. Described by Martin Luther King as ‘the queen of American folk music’, Holmes included The Foggy Dew on her 1959 album My Eyes Have Seen.

As his health began to deteriorate, one of O’Neill’s last official duties was to bless a new site for St Mary’s Church in Newcastle, Co. Down. In spring 1963 he was admitted to the Royal Victoria Hospital, Belfast. Unresponsive to medical treatment, he received the Last Rites just before he died on 18 May 1963. Three days later, the seaside town of Newcastle was brought to a standstill in order to accommodate the mile-long cortège of mourners following behind the hearse, the heavy holiday traffic being diverted by the Royal Ulster Constabulary. Soon after, Benedict Kiely acknowledged receipt of two letters from readers of his regular Irish Press column. One claimed that, according to the Our Boys magazine, The Foggy Dew was written by ‘a nun’, while the other reader suspected that it was written by ‘a Charles O’Neill’. A more informed Kiely reminded the correspondent that Revd Mother Columba, an Ursuline nun, in fact wrote Who Fears to Speak of Easter Week on 3 May 1916 when ‘news of the executions became known’.

Legacy

Luke Kelly, the Clancy Brothers, the Wolfe Tones, Shane MacGowan, Damien Dempsey and Sinead O’Connor are just some of the artists who have recorded The Foggy Dew. Though it proved a great source of regret for Kiely that he did not get the chance to meet the men behind the ‘immortal song’, he felt assured that people would have a lot to say about Father Charles O’Neill and Carl Hardebeck in the future.

Eugene Dunphy is a music teacher in Belfast; he is currently writing a biography of Carl Hardebeck.

FURTHER READING

G. Allen, ‘The Blind Bard of Belfast, Carl Gilbert Hardebeck (1869–1945)’, History Ireland 6 (3) (1998).

S. Neeson, ‘Carl Gilbert Hardebeck’, Capuchin Annual (1965).