A Forgotten Army; The Irish Yeomanry

Published in 18th–19th - Century History, Early Modern History (1500–1700), Features, Issue 4 (Winter 1996), Volume 4

‘Peep O’Day Boys’, from Daly’s Ireland in ’98(1888). Despite the title the uniforms suggest that villians in the picture are Yeomanry, a reflection of their notoriety in folk memory.

In September 1796, Ireland was pregnant with expectation. The United Irishmen and Defenders planned insurrection and a French invasion was imminent. On 19 September Dublin Castle announced plans to follow Britain’s lead and enlist civilian volunteers as a yeomanry force. In October commissions were issued to local gentlemen and magistrates empowering them to raise cavalry troops and infantry companies. Recruits took the ‘Yeomanry oath’, were officered by the local gentry but were paid, clothed, armed and controlled by government. Their remit was to free the regular army and militia from domestic peacekeeping and do garrison duty if invasion meant troops had to move

to the coast. Service was part-time—usually two ‘exercise days’ per week—except during emergencies when they were called up on ‘permanent duty’.

Folk memory

If the Irish Yeomanry are remembered at all it is usually for their notoriety in the bloody summer of 1798. The popular folk memory of every area which saw action supplies lurid stories from the burning of Father John Murphy’s corpse in a tar barrel at Tullow to the sabreing and mutilation of Betsy Gray after the battle of Ballynahinch. Until recently, the Yeomen have been largely written out of history, apart from early nineteenth century polemics where they appear either as a brutal mob making ‘croppies’ lie down or latter day Williamite saviours. Such neglect belies the Irish Yeomanry’s real significance.

When Belfast’s White Linen Hall was demolished in 1896 to make way for City Hall a glass phial containing a scroll bearing Volunteer reform resolutions was found in its foundations. Two years later another demolition occurred. Ballynahinch loyalists smashed the monument on Betsy Gray’s grave to prevent a 1798 centenary celebration by Belfast Home Rulers. Volunteer radicalism was hermetically sealed in the past while the passions and polarisation engendered in the later 1790s lived and breathed. The Irish Yeomanry played a key role in this critical transition which saw ancient antipathies sharpen and re-assert their baleful influence after a period of relative calm. The ‘Age of Reason’ had briefly promised a brave new world in Ireland. In the 1780s, radical Volunteers favoured Catholic relief along with parliamentary reform. The Boyne Societies, founded to perpetuate the Williamite cause, charged toasting glasses rather than muskets. However the prospect of revolutionary change proved too much to swallow.

Flag of the Lower lveagh Yeoman Cavalry.

(Reproduced with the kind permission of the Trustees of the Ulster Museum, Belfast)

Context of formation

The force raised in 1796 actually bore much more resemblance to the Volunteers, praised by United Irish writers Myles Byrne and Charles Teeling, than to the reactionary and bigoted organisation portrayed in their rebellion histories. In reality, loyalism in 1796 was still a relatively broad church containing an ideological diversity and fluidity reminiscent of Volunteering days. Indeed, the Yeomanry were largely based on the same membership constituency, with frequent continuity of individual or family service. They certainly included the Williamite tradition found in some Volunteer corps but it also encompassed much of the democratic and indeed radical volunteering spirit. Election of officers was common everywhere. Dublin Yeomen, whom Henry Joy McCracken thought ‘liberal’, also elected their captains despite governmental opposition. Even in Armagh, the cockpit of Orangeism, Yeomen varied from Diamond veterans in the Crowhill infantry to radical ex-Volunteers enrolled by Lord Charlemont despite quibbles over the oath and the inclusion of some erstwhile francophiles who had recently erected a liberty tree.

In 1796, there was no inconsistency about this. Grattan dubbed the Yeomanry ‘an ascendancy army’ but in reality the United Irishmen were in the ascendant while the loyalist response was fragmented and in danger of being overwhelmed. The initial priority was defence: to trawl in all varieties of loyalty and provide a structure to prevent people being neutralised or becoming United Irishmen.

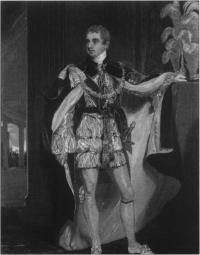

Castlereagh

More Catholics than Orangemen

The new Yeomanry was therefore a surprisingly diverse force, given its subsequent reputation. The government denied any intention of excluding Catholics or Presbyterians but the system already had the potential for denominational

and ideological filtering. Being a Yeoman was a desirable position conveying social status plus pay, clothing, arms and training. Applications exceeded places, which were limited by financial and security considerations. This meant selection locally and government reliance on local landowners’ judgement.

Sometimes recruits had no choice. In some areas only Protestants volunteered, in others the Catholic Committee sabotaged Catholic enlistment. In Loughinsholin, where Presbyterians offered Catholics withdrew and vice-versa. Where there was competition to enter a limited number of corps, choices were unavoidable. Downshire allowed Catholics in his cavalry but faced mutually exclusive Protestant and Catholic infantry offers from the same parishes and opted for the former. In Orange areas, some landowners deliberately selected their Yeomen directly from the local lodge. Occasionally a precarious balance was attempted by including proportions of Catholic, Protestant and Dissenter. The Farney corps in Monaghan started this way. However the first levy produced a predominantly Anglican force. There were Presbyterian Yeomen in mid-Ulster but the strength of the United Irishmen in eastern counties meant relatively few corps were raised there in 1796.

Wealthy, property-owning Catholics, on the other hand, were admitted into cavalry corps. There was an element of tokenism in this: Yeomanry offers of service sometimes highlighted Catholic members, which they never did for the Protestant denominations. In this way it can be estimated that at the very least ten per cent of the first national levy of 20,000 Yeomen were Catholic, thus outnumbering the Orange yeomen who in 1796 were only to be found in some corps in the Orange districts of mid-Ulster.

Forming a Yeomanry force in the deteriorating conditions of 1796 gave the initiative briefly back to Dublin Castle but this disappeared in the crisis following the Bantry Bay invasion attempt. The United Irishmen drew great encouragement from its near success and felt themselves strong enough to switch their policy on the Yeomanry from intimidation to infiltration. As a response, purges of Yeomanry corps began in Ulster and Leinster in the spring of 1797.

Orange links

Many Catholics were expelled from corps in Wicklow and Wexford on suspicion of being ‘United’. In mid-Ulster General John Knox devised a ‘test oath’ obliging Yeomen to publicly swear they were not United Irishmen. This got results and several corps were cleared of disaffected members. The Presbyterian secretary of the Farney corps was expelled following his confession of United Irish membership while Catholics were removed on the pretext of a political resolution they had issued. Knox followed up the expulsions by permitting augmentations of Orangemen into some northern corps. Although Orangemen quietly joined some corps in 1796 this was the first time they had official approval.

Knox clinched this by engineering Orange resolutions for Castle consumption. This was a risky strategy, given the recent disturbances in Armagh. Knox, a correspondent of the radical MP Arthur O’Connor, privately disapproved of Orangeism but believed the dangerous predicament he faced merited utilising it as a short-term expedient. However, with the United Irish-Defender alliance growing, the precedent inherent in this strategy would have profound and lasting consequences. Almost immediately, symptoms of polarisation appeared. A Tyrone clergyman noted approvingly, ‘Our parties are all obviously merged into two: loyalists and traitors’.

Castlereagh’s secret policy

However the critical Yeomanry-Orange connection was still to come. By 1798 Orangeism had been adopted by many northern gentry and spread to Dublin where a framework national organisation was established. As insurrection loomed, this provided a ready-made supply of loyal manpower. There were around 18,000 Yeomen in Ulster whereas the Orangemen were conservatively reckoned at 40,000. In March the Dublin leaders offered the Ulster Orangemen to the government if it would arm them. The viceroy, Camden, was scared of offending Catholics in the Militia and hestitated. However, the appointment of an Irishman—Lord Castlereagh—as acting chief secretary offered a solution. On 16 April 1798 he ordered northern Yeomanry commanders to organise 5,000 ‘supplementary’ men to be armed in an emergency. Camden and Castlereagh had privately decided that, where possible, these would be Orangemen.

In tandem with the supplementary plan, regular Yeomen were given a more military role. They were put on permanent duty and integrated into contingency plans for garrisoning key towns at the outbreak of trouble. This had one very important side-effect. In the cramped conditions of garrison life and the panic occasioned by the influx of rural loyalists, Orangeism spread like wildfire amongst both Yeomanry and regular units. This spontaneous, ground-level spread of Orangeism operated simultaneously with Castlereagh’s secret emergency policy to utilise Orange manpower in Ulster. The Yeomanry system proved the ideal facilitator for both.

![Drum of the Aughnahoe[County Tyrone] Yeoman Infantry. (Reproduced with the kind permission of the Trustees of the Ulster Museum, Belfast)](/wp-content/uploads/2013/02/87_small_1305287224.jpg)

Drum of the Aughnahoe[County Tyrone] Yeoman Infantry. (Reproduced with the kind permission of the Trustees of the Ulster Museum, Belfast)

On 1 July 1798 in the Presbyterian town of Belfast, once the epicentre of United Irish activity, it was noted that ‘Every man…has a red coat on’. This would have been inconceivable in 1796 when there was great difficulty enlisting Yeomen. However, it was now government policy to separate northern Presbyterians from the United Irishmen. Again the Yeomanry played a key role. Castlereagh admitted privately that the arrest of the Down United colonel, William Steel Dickson was an exception to ‘the policy of acting against the Catholick [sic] rather than the Presbyterian members of the union [United Irishmen]’. Government supporters industriously spread news of the Scullabogue massacre (See HI Autumn 1996) to stir up atavistic fears. The Yeomanry was expanded considerably to meet the emergency and ex-radicals were no longer discouraged. In effect, the Yeomanry functioned as a safety net. Joining up offered an acceptable and very public ‘way back’ for wavering radicals. Although there were some Presbyterian Yeomen in 1796, many more joined in mid-1798. Charlemont’s friend, the Anglican clergyman Edward Hudson, exploited a ‘schism’ between Presbyterian and Catholic to enlist the former in his Portglenone corps, sardonically noting ‘the brotherhood of affection is over’. By 1799, he claimed ‘the word “Protestant”, which was becoming obsolete in the north, has regained its influence and all of that description seem drawing closer together’. Thus the Yeomanry oath was often a rite of passage for Presbyterians keen to end their flirtation with revolution.

Loyalty re-defined

The 1798 rebellion had a profound impact on the psyche of Protestant Ireland, conjuring up anew spectres of 1641. When news of the rising hit Dublin, Camden described the apocalyptic atmosphere to Pitt. The rebellion

literally made the Protestant part of this country mad…it is scarcely possible to restrain the violence of my own immediate friends and advisors…they are prepared for extirpation and any appearance of lenity…raises a flame which runs like wildfire thro’ the streets.

Mercy was indeed scarce until Cornwallis replaced Camden and the rebellion was effectively crushed. Up to this juncture, the interests of most Protestants and the government were running parallel, a partnership potently symbolised by the Yeomanry, now blooded in the rebellion. Many embattled Protestants saw the parallel interests as identical: through the smouldering fires of rebellion they confused expediency with permanent policy.

Cornwallis, a professional soldier, voiced his contempt for the barbarity of the local amateur forces, particularly the Yeomanry. For many, criticism of the Yeomanry was construed as attacking Protestant interests. Yeomanry service under Camden and the relationship it represented was now seen as an unalterable ‘gold standard’. When government policy ran counter to perceived Protestant interests, loyalty was qualified with distrust and a feeling of betrayal. Camden was toasted as ‘the father of the Yeomanry’ while Cornwallis was lampooned as ‘Croppywallis’.

Lt. Col. William Blacker, Yeoman and Oraneman

(Dublin University Magazine 1841)

The Yeomanry and the Union

When it emerged that Pitt intended legislative union, antagonism towards Cornwallis sharpened. As union would remove emancipation from Ireland’s control, ultra-Protestant loyalty faced a severe test. Many Yeomen and Orangemen opposed the measure, particularly in Dublin where lawyers and merchants also faced a loss of professional and mercantile status. The Yeomanry, which it was claimed saved Ireland in 1798, were at the cutting edge of the anti-union campaign. A mutiny was threatened in Dublin with Volunteer-type rhetoric, but the bluster of 1782 proved hot air in post-rebellion Ireland. In the last analysis Protestants depended on the Yeomanry and the Yeomen depended on the government. The consequences of disbandment made union seem the lesser evil. Cornwallis rushed reinforcements to Dublin but the bluff had called itself.

Jonah Barrington later claimed the Volunteers were loyal to their country [Ireland] and their king while the Yeomen looked to ‘the king of England and his ministers’. Barrington’s jibe about patriotism was the peevish reaction of an incorrigible anti-unionist, yet a subtle alteration in the nature and focus of loyalty had occurred. The Volunteers’ ‘patriotism’ flourished in an atmosphere where they faced no real internal threat. While many Yeomen opposed the abolition of the Irish parliament, the experience of 1798 made challenging the executive a luxury they could not afford. On the surface, the switch of loyalty from College Green to Dublin Castle seemed relatively smooth: Yeomanry corps quickly adopted the post-1800 union flag in their colours. Yet, alongside this, a new focus of loyalty emerged to co-exist with this sometimes grudging allegiance. The ‘Protestant nationalism’ of 1782 was transformed into a clenching loyalty to the increasingly insecure interests of Irish Protestants.

Politicisation and Protestantism

The Yeomanry soon became a major component in post-union politics, a conduit between government and substantial numbers of Protestants who increasingly saw the force as symbolising the survival of their social and political position. They functioned as a political tool. When Hardwicke, the new viceroy, wanted to send a conciliatory message to nervous Protestants he reviewed the entire Dublin Yeomanry in Phoenix Park, then lavished hospitality on the officers in a banquet afterwards. It was a two-way process: Protestants could use the Yeomanry to put government in their debt. The continuance of war in 1803 meant a large increase in the Yeomanry from 63,000 to around 80,000. Emmet’s rising, coming when this augmentation was on foot, gave Protestants another opportunity to appear indispensable by extending their monopoly of the Yeomanry. The means by which this was accomplished ranged from high-level manoeuvring to parish pump politics.

As a partisan Yeomanry would be viewed in a poor light at Westminster, Hardwicke attempted a balance by considering some purely Catholic corps. However the Louth MP Fortesque threatened impeachment if he proceeded. Even the chief secretary, Wickham, considered Catholic corps ‘unsafe’ as they would inflame loyalist opinion and ‘be not cried but roared out against throughout all Ireland’. At a local level, Arthur Browne, the Prime Sergeant of Limerick, observed that Yeomanry corps in each town he passed on circuit effectively excluded Catholics by submitting prospective recruits to a ballot of existing members. This said, the Protestant monopoly was never total. Catholic Yeomen remained in areas of sparse Protestant settlement like Kerry. Moreover, there was still a scattering of liberal Protestants, usually at officer level, like Lieutenant Barnes of the Armagh Yeomanry. However, the general tendency was clear. When it became known Barnes had signed an emancipation petition, the privates mutinied and flung down their arms.

Catholic attitudes

In the early nineteenth century, the passions generated by 1798 mixed with the politics of the Catholic Question. The continued existence of the Yeomanry allowed Protestants to demonstrate that their traditional control of law and order was intact as the campaign for emancipation built up. Yeomanry parades and the use of the force in assisting magistrates with mundane law and order matters assumed great symbolic importance as tangible manifestations of the fractures in Irish society. Yeomanry corps inevitably became involved in local clashes in an increasingly sectarianised atmosphere. In 1807, the government prevented Enniscorthy Yeomen celebrating the anniversary of the battle of Vinegar Hill as it raised sectarian tensions. In 1808 Yeomen were among a mob which disrupted a St John’s Eve bonfire and ‘garland’ near Newry, provoking a riot in which one man died. During the disturbances which swept Kerry and Limerick the same year, isolated Protestant Yeomen were singled out for attacks and arms raids. Since penal times, possession or dispossession of arms scored political points. Protestant insecurity and Catholic alienation fed off each other. O’Connell, ironically once a Yeoman himself, upped the ante by lambasting the force as symbolising a partisan magistracy.

The Yeomanry presented governments with a dilemma: was their strategic utility worth the political price? While war with France continued and the regular army was depleted for overseas service, they provided an important source of additional manpower and were particularly useful during invasion scares when they could free up the remaining regular garrison and maintain a local presence to deter co-ordinated action by the disaffected. Moreover, they served an unofficial purpose by keeping potentially turbulent Protestants under discipline.

The decision was deferred and the dilemma submerged. For much of the 1820s the Yeomanry lingered on, a rather moribund force seen by officials as a liability which could not be disbanded for fear of a Protestant reaction, particularly in Ulster where the force was numerically strongest. The advent of the denominationally inclusive County Constabulary in 1822 further touched Protestant insecurity by removing much of the functional justification for Yeomanry. There was no love lost between the two forces. In 1830 William McMullan of the Lurgan infantry was arrested by his own captain, yelling at the head of a mob rioting against the police, ‘we have plenty of arms and ammunition and can use them as well as you’. Ironically in that year the Whig chief secretary, Stanley, had decided to re-clothe and re-arm the Yeomanry as part of the response to the southern Tithe War. Stanley’s experiment proved disastrous as sectarian clashes developed.

In some districts the sight of a red coat was like a red rag to a bull. In 1831, the rescue of two heifers destrained for tithe sparked an appalling incident in Newtownbarry. A mob of locals tried to release the cattle, the magistrates called for Yeomanry and stones were thrown. When one Yeoman fell with a fractured skull, the others opened fire killing fourteen countrymen. The viceroy, Anglesey, tried to limit the political damage by initiating a progressive dismantling of the Yeomanry starting with a stand-down of the permanent sergeants which meant the Yeomen could no longer drill. This phasing-out took three years and was intentionally gradual, starving the Yeomanry of the oxygen of duty and pay, thus letting them pass away naturally if not gracefully. It was rightly felt this approach would be less likely to provoke a political reaction than sudden disbandment which, for a Protestant community coming to terms with emancipation, would have been like an amputation without anaesthetic.

![Yeomanry belt plates - Glenauly [County Fermanagh]Infantry and Belfast Merchant's Crops. (Reproduced with the kind permission of the Trustees of the Ulster Museum, Belfast)](/wp-content/uploads/2013/02/87_small_1305287613.jpg)

Yeomanry belt plates – Glenauly [County Fermanagh]

Infantry and Belfast Merchant’s Crops. (Reproduced with the kind permission of the Trustees of the Ulster Museum, Belfast)

Although the Yeomanry’s official existence ended in 1834, the last rusty muskets were not removed from their dusty stores till the early 1840s. With unintentional but obvious symbolism, they were escorted to the ordnance stores by members of the new constabulary. Although gone, the Yeomen were most certainly not forgotten. For one thing, they were seen as the most recent manifestation of a tradition of Protestant self-defence stretching back to plantation requirements of armed service from tenants then re-surfacing in different forms such as the Williamite county associations, the eighteenth-century Boyne Societies, anti-Jacobite associations of 1745 and the Volunteers. Such identification had been eagerly promoted. At the foundation of an Apprentice Boys’ club in 1813, Colonel Blacker, a Yeoman and Orangeman, amalgamated the siege tradition, the Yeomanry and 1798 in a song entitled The Crimson Banner:

Again when treason maddened round,

and rebel hordes were swarming,

were Derry’s sons the foremost found,

for King and Country arming.

Moreover, the idea of a yeomanry remained as a structural template for local, gentry-led self-defence, particularly in Ulster. When volunteering was revived in Britain in 1859, northern Irish MPs like Sharman Crawford tried unsuccessfully to use the Yeomanry precedent to get similar Irish legislation. Yeomanry-like associations were mooted in the second Home Rule crisis of 1893. The Ulster Volunteer Force of 1911-14—often led by the same families like Knox of Dungannon—defined their role like Yeomen, giving priority to local defence and exhibiting great reluctance to leave their own districts for training in brigades.

The strong Orange-Yeomanry connection—itself part of a wider process of militarisation in Irish society—has left an enduring imprint on Orangeism which can be seen in the marching fife and drum bands and in various military regalia such as ceremonial swords and pikes. Even the name is still retained by the Moira Yeomanry Loyal Orange Lodge. The town or parish basis of Yeomanry corps mirrored the dynamics of the plantations and helped catapult the territorial mind-set of both ‘planter’ and ‘native’ into the nineteenth century and beyond. Weekly Yeomanry parades defined territory in the same way as rural drumming parties in the nineteenth century and marches, murals and coloured kerbstones in the twentieth.

Alan Blackstock works in the Public Records Office, Northern Ireland.

Further reading:

The formation of the Orange Order, 1795-98: the edited papers of Colonel William Blacker and Colonel Robert H. Wallace (Belfast 1994).

T. Bartlett, The Fall and Rise of the Irish Nation (Dublin 1992).

G. Broeker, Rural Disorder and Police Reform in Ireland, 1812-36 (London 1970).

H. Senior, Orangeism in Ireland and Britain, 1795-1836 (London and Toronto 1966).