A case of thoughtless vandalism

Published in 18th–19th - Century History, Issue 1 (Jan/Feb 2006), News, Volume 14The apparently imminent closure of the Mountjoy prison complex on Dublin’s North Circular Road has raised a number of well-publicised issues. Do we need another prison? Is the site at Thornton the best site? Was e29m a fair price?

I don’t have a vested interest in any of these issues. What I do have a vested interest in is what happens to Mountjoy prison when it is finally closed. Its future as one of our most important historic locations is in real doubt as the Minister for Justice, Michael McDowell, has decided to demolish the prison and hand it over, with carte blanche, to whatever developer is willing to pay the highest price.

Mountjoy is a place of huge significance. Its history is one of truly epic proportions. It has been the main place of incarceration and punishment in Ireland since 1850, and over 500,000 prisoners have passed through its doors. It has been the cracked mirror of society that has reflected us at our worst, our most desperate, and our most tragic. Mountjoy’s story is linked to the final years of the transportation system. It was the first major government prison and put the state at the centre of our prison system. Among the hundreds of Fenian prisoners held there was Jeremiah O’Donovan Rossa. Pat Nally of the eponymous Nally Stand in Croke Park died there from ill treatment in 1891. Suffragettes went on hunger strike there for the vote for women before World War I. Jim Larkin and James Connolly were held there during labour disputes. Mountjoy was at the forefront of the post-1916 republican movement. Thomas Ashe died from forced feeding in Mountjoy. Kevin Barry and ten others were executed there during the War of Independence. In the Civil War Mountjoy was where most of the important anti-Treaty figures were held. The first four republicans to be executed during the Civil War were shot there by firing squad on 8 December 1922. The massive hunger strike that was the last throw of the dice of the Civil War started in Mountjoy in October 1923. Brendan Behan was held there during World War II and began his writing career in Mountjoy.

Once the prison is demolished its memory becomes a very tenuous thing. If it is not physically there it recedes from the collective consciousness. Countless stories become abstract instead of being rooted in a reality of stone and mortar. I do not advocate keeping it as a prison if that means keeping prisoners in poor conditions. Neither do I advocate mothballing the site and turning it into a museum. Turning Mountjoy into a museum like Kilmainham Gaol is not an option. While their stories are different, is there really room in Dublin for two prison museums? I think not.

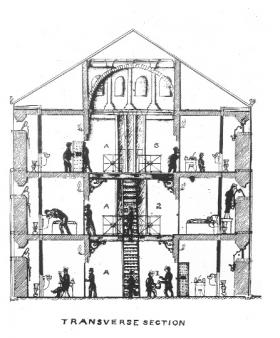

Transverse section of ‘A’ wing—one of several drawings confiscated from prisoner William MacDonagh in the 1860s. (National Archives of Ireland)

Other countries have undertaken reuse studies to recognise the importance of the history associated with such buildings. Has this been done by any competent person in the Department of Justice, or was it decided over a cup of coffee in some staff canteen? There is no doubt that prisons can be difficult buildings to convert to other uses, but it is by no means impossible. A number have been transformed into hotels of varying standard—from hostel-type accommodation to four-star.

Shortly after I started to work in Kilmainham Gaol in 1995 my partner and I went to Prague for a weekend. With thoughts of my new place of employment on my mind, I remarked that it would be interesting to see where Vaclav Havel was imprisoned during the communist era. When we arrived at our hotel, there had been a problem with the booking and there was no room for us. They said they would find us other accommodation. Lo and behold, it was the very prison where Havel was held and which had been converted into the Unitas Pension Hotel.

Development has to happen. But this does not mean that a developer needs to be given a clear site to work with. It is becoming increasingly recognised that heritage and development are not mutually exclusive concepts, and indeed, if engaged with a bit of imagination, can be mutually reinforcing and beneficial. For example, an English property developer, Urban Splash, has made a name for itself adapting important historic buildings to contemporary uses such as apartments. (Their work includes the Lister Mills complex in Bradford.) There is no reason why Mountjoy could not be developed in a modern, attractive way. But no, we are adopting the Neanderthal approach.

Michael McDowell has said that he is going to save Mountjoy’s hang-house. He is going to have it relocated to Kilmainham Gaol Museum, as if that makes everything OK. This is trite and cynical in the extreme. Why has he decided that this is the only part of all of the history of the prison that is worth saving? What process was gone through? Where is the study that has informed this decision?

It is hugely ironic that he has not mentioned the 41 ‘ordinary’ criminals who were executed there, because these could present his biggest headache. The bodies of these 40 men (including William Mitchell, a Black-and-Tan) and one woman are still buried in the prison. The general location of their bodies is known, but not exactly where each is buried.

What is going to happen to these bodies? Will their remains be incorporated into an apartment complex? Will the burial area be fenced off and made into some sort of crass commemorative park? What if one of the families asks for the remains of their loved one to be returned to them? Just what are the plans? As they were buried in the prison as part of their sentence, once Mountjoy ceases to be a prison what is the legal position? Those who have suffered the ultimate penalty that was once available to the state may have some retribution in store for the minister when the diggers go in.

I like to think that books matter, that somehow the thoughts and information set down between two covers can change the way people think. In relation to my own study of Mountjoy, I have in my files a letter from the then attorney-general complimenting me on the book. It was from Michael McDowell, now our minister for justice. That he thought the book ‘excellent’ unfortunately has not influenced his attempt to consign Mountjoy prison to historic obscurity in a case of thoughtless vandalism.

Tim Carey formerly worked in Kilmainham Gaol Museum and is the author of Mountjoy: the story of a prison (Collins Press, 2000).