‘A BUZZ IN THE AIR’—FIRST FLIGHTS TO IRELAND, APRIL 1912

Published in Features, Issue 4 (July/August 2023), Volume 31By Peadar Slattery

Above: Denys Corbett Wilson—the first person to fly from Britain to Ireland—beside his Blériot XI, the aeroplane used in all three attempts to cross the Irish Sea in April 1912. (Donal McCarron collection)

Ask anyone in Ireland to recall an event in 1912 and they may well mention the sinking of the White Star liner Titanic on 14–15 April, or a person might point to the signing of the Solemn League and Covenant by unionists to resist Home Rule. Less well known is an episode in April of that year when three aviators set out to fly from Britain to Ireland, a feat not achieved before.

In 1912 aviation was new, the Wright brothers having flown for the first time on 17 December 1903 at Kill Devil Hills, Kitty Hawk, North Carolina, with their flight lasting 59 seconds. Seven years later, in 1910, Louis Blériot flew from France to England in 36 minutes, a distance over water of 22 miles. In the same year, Robert Loraine, actor and aviator and a friend of George Bernard Shaw, who flew from Holyhead in Wales across the Irish Sea, was not so successful, coming down in the sea a few hundred yards from Howth Head and swimming ashore. He was disgusted that instead of soaring over Dublin he ended up on board the SS Adela, ‘steaming up the Liffey on this little cargo boat’.

BLÉRIOT AIRCRAFT

The challenge of the Irish Sea remained. There were pioneer Irish aviators—Harry Ferguson from Belfast, the first to fly in Ireland in December 1909, and Lilian Bland from Carnmoney, Co. Antrim, who first flew in 1910, the first woman to do so in Ireland. Neither attempted the Irish Sea crossing. Both gave up flying: Ferguson subsequently developed tractors commercially, and Bland’s father, who worried about her dangerous aviation experiments, enticed her away from flying by bribing her with a Ford car bought in Archer’s garage in Dublin.

After his cross-channel flight, Blériot responded to the demand for his aircraft by manufacturing the Blériot XI aeroplane for sale. They were available in France and at Hendon aerodrome in north-west London, where he had stocks of the plane in five hangars. He also set up flying schools at Rouen, at Pau in the south of France and at Hendon.

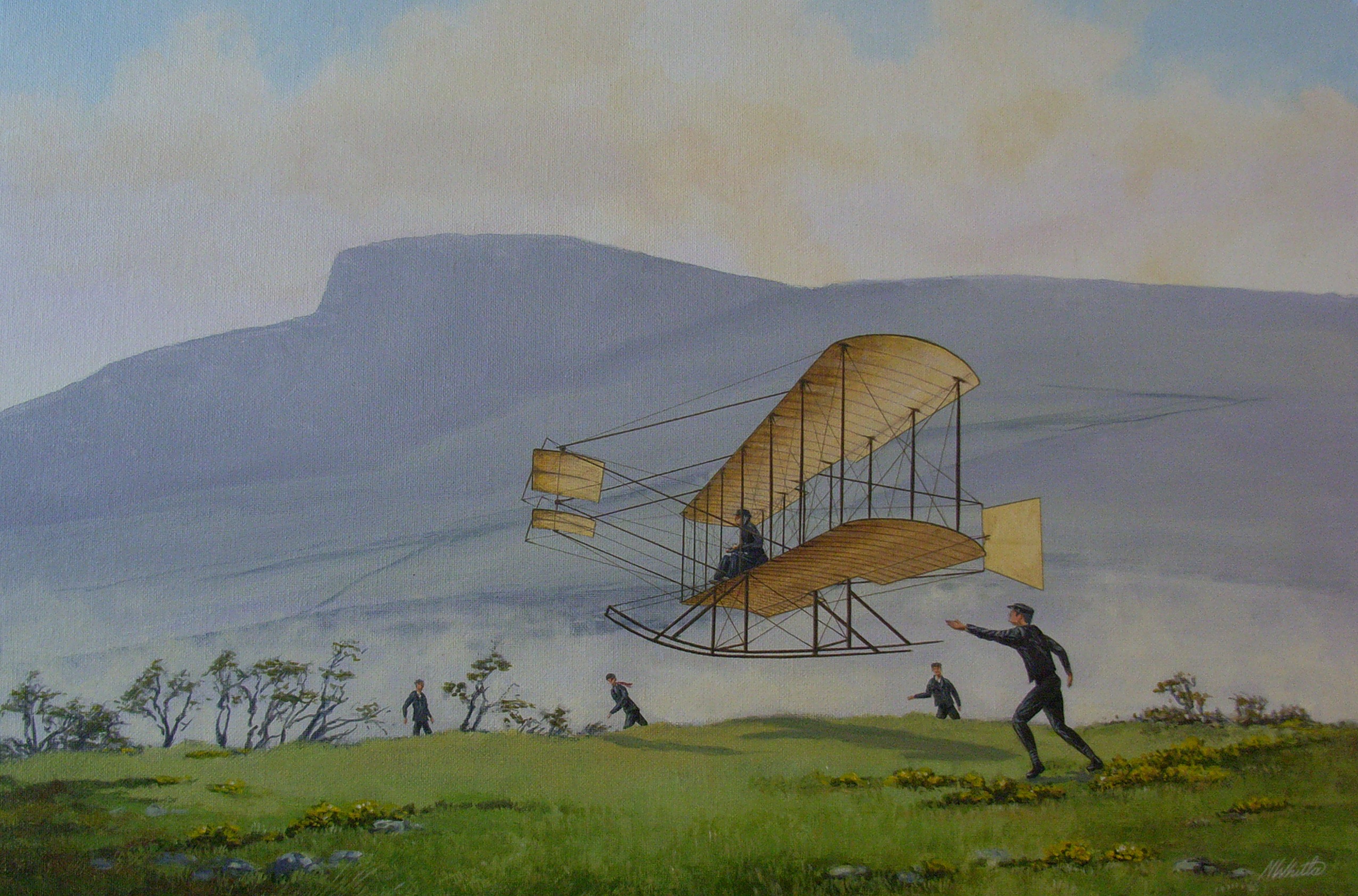

Above: A painting by Norman Whitla of Lilian Bland in her glider on Carnmoney Hill, Co. Antrim. (Antrim and Newtownabbey Borough Council)

Three aviators, who each owned a Blériot XI, set their hearts on flying from Britain to Ireland: naval architect Damer Leslie Allen from Limerick; Vivian Hewitt, a wealthy engineer from Rhyl in north Wales; and Denys Corbett Wilson, who fought in the Boer War and whose mother had family connections in Kilkenny. They each gained their aviator’s licence in 1912. Corbett Wilson learned to fly at Pau, Allen learned at Hendon, and Hewitt first learned flying skills in a glider, as the Wright brothers and Lilian Bland had done, before doing basic training in an aeroplane at Brooklands in south London.

THREE FLIGHTS

The three flights from Britain to Ireland that took place from 18 to 26 April produced all of the elements of later aviation history—success, failure, glory, danger, aircraft damage, flight problems, a crash landing and loss of life.

Corbett Wilson and Allen knew each other and decided to fly to Ireland, both initially setting out from Hendon on 17 April. They became separated and Allen landed at Chester racecourse. His engine was checked by a mechanic, and on 18 April he took off from the racecourse and was seen flying south of Holyhead at Trearddur Bay at 8am, heading west. Neither he nor his aeroplane were seen again, and he was recorded as lost at sea.

On the previous day Hewitt had been in London, staying at the Savoy Hotel, and learned that Allen was flying to Holyhead and on to Ireland. Next day, he saw late morning newspaper editions reporting that Allen had set out from Holyhead, but later in the day newspaper placards carried the news ‘Missing Airman’, while evening newspapers reported ‘Airman Lost at Sea’. Hewitt could still achieve his cherished ambition of being the first to fly from Britain to Ireland, provided that he could get from London to Rhyl, assemble his aeroplane, which had been dismantled for servicing, and get it into flying condition. He drove through the night in his racing car, arriving in Rhyl early next morning.

Meanwhile, Corbett Wilson, having first come down near Hereford, finally landed on the coast at Fishguard. On 22 April he set out from there for Ireland and landed successfully in a field near Enniscorthy, after a flight of 1 hour 40 minutes, the journey over water covering 62 miles. He was the first to fly from Britain to Ireland and in so doing had crossed St George’s Channel. The flight was not easy, as Corbett Wilson described:

‘I ran into a squall, wind and rain and most unpleasant; whatever height I tried, it was bad. After about 30 minutes of it the motor began to miss; the compass was also behaving erratically and visibility was bad. I had difficulty in keeping my course.’

He described how he landed in fog and did not realise that the field was so small. It was a bumpy landing, finishing at a stone-faced bank, damaging the propellor and the plane’s undercarriage, though Corbett Wilson was uninjured.

HEWITT’S FLIGHT

Four days later, on 26 April, Hewitt set out from Holyhead and arrived in Dublin in 1 hour 15 minutes. He had crossed the Irish Sea and flown over water about the same distance as Corbett Wilson had done. He dealt with some dangerous situations on his flight but landed smoothly and uneventfully in the Fifteen Acres in Phoenix Park.

Above: Vivian Hewitt about to leave Rhyl for Holyhead on 22 April 1912 to begin his flight to Dublin. (Hewitt–Hywel collection).

Initially, Hewitt took off from his hometown of Rhyl on 22 April and only got as far as Holyhead owing to a thick haze. Although eager to fly to Dublin on the next day, he was advised strongly against flying by the captain of the mail-boat because he would be running ‘a great risk’ with misty conditions in the Irish Sea. While waiting patiently for a further three days, Hewitt learned that Corbett Wilson had flown to Ireland, and wrote to the editor of The Aeroplane to tell him of his intentions:

‘You no doubt have heard that I am attempting to cross the Irish Sea. Wilson crossed the St George’s Channel safely, and I am up here now waiting for fine weather to do this other crossing.’

He set out for Dublin on 26 April when there was a favourable wind.

The flight was not easy. Having taken off from Holyhead at 10.30am, Hewitt described how he had a difficult flight across the Irish Sea, ‘the machine going on its side twice’, and on one occasion he was ‘nearly thrown out’ of his seat. Realising at one point that he was off course, because of thick haze and a ‘bank of dense fog’, and heading for the Wicklow Mountains, he had time to redirect his aeroplane along the coast until he came to Dublin Bay, where he picked up the course of the Liffey, which he described as being ‘of great use to me’. Over Trinity College his plane was almost turned upside down, and over Guinness’s his speed dropped from 70mph to 20mph and he thought that he would end up in the Liffey.

Hewitt was in his early twenties but was described as a smiling eighteen-year-old when he stepped out of his plane in the Fifteen Acres. The adjutant of the nearby Royal Hibernian School, now St Mary’s Hospital, welcomed and entertained Hewitt, and it was from there that he began to send telegrams to friends in Wales to let them know of his success. His plane had been seen over Dublin and large crowds on foot, on bicycles and in motor cars made their way to the Park to view his machine. Pressmen turned up ‘armed with pencil and camera’ to interview him, which he thoroughly enjoyed. He was photographed, and the autograph-hunters crowded around too. The police, on foot and mounted, kept order and protected Hewitt’s plane.

Fifty years after his flight, Vivian Hewitt was back in Dublin, staying in the Gresham Hotel, and was encouraged to go to the Fifteen Acres and ‘see the exact spot’ where he had landed. In the Phoenix Park he ‘recognised certain landmarks and recalled facts and experiences which had lain dormant in his memory’. In truth, he had never forgotten his achievement and it has always been remembered in Rhyl, his initial starting point for his flight to Dublin.

In 2022 Corbett Wilson’s achievement was commemorated on its centenary at Crane, Co. Wexford, and at Enniscorthy Castle. Surely, it is now time—111 years later—that Hewitt’s flight into Dublin should also be officially celebrated and honoured permanently?

Peadar Slattery was awarded a doctorate in modern history by Trinity College, Dublin, and is the author of Social life in pre-Reformation Dublin, 1450–1540 (Four Courts Press, 2019).

Further reading

L. Byrne, History of aviation in Ireland (Dublin, 1980).

W. Hywel, Modest millionaire: the biography of Captain Vivian Hewitt (Denbigh, 1973).

D. MacCarron (ed.), Letters from an early bird: the life and letters of Denys Corbett Wilson, 1882–1915 (Barnsley, 2006).

B. Montgomery, Early aviation in Ireland (Garristown, 2013).