100 YEARS AGO: The Black and Tans are deployed

Published in Issue 2 (March/April 2020), Volume 28By Joseph E.A. Connell Jr

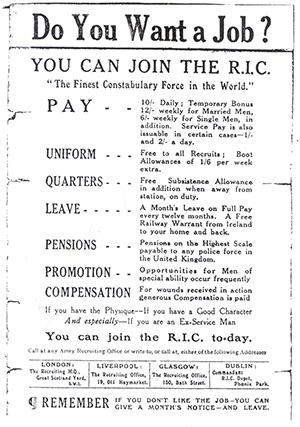

Above: ‘If you have the Physique—If you have a Good Character—And especially—If you are an Ex-Service Man You can join the R.I.C. to-day’—a recruitment poster for the Black and Tans.

The arrival of the Black and Tans in March 1920 changed the entire complexion of the War of Independence. These ‘irregulars’ were established as a section of the Royal Irish Constabulary (RIC) and first appeared in the village of Upperchurch, Co. Tipperary. The British government needed more troops in Ireland to maintain its position, and turned to unemployed demobilised soldiers from the First World War. The name came from their uniforms, which were dark green (almost black) tunics and tan or khaki trousers, some with civilian hats but most with RIC caps and black leather belts. The name was given to them by Christopher O’Sullivan, editor of the Limerick Echo, who wrote that they reminded him of a pack of hunting dogs in Limerick: ‘Judging by the colour of their cap and trousers, they resembled something one would associate with the Scarteen Hunt’.

The second British force to augment the regular armed forces was the Auxiliaries (‘Auxies’), who arrived in September 1920. Auxiliary to the RIC, they were originally called ‘temporary cadets’ but were ‘graded as RIC sergeants for the purpose of discipline’. They were apparently intractable, even to their own authority. They were feared and hated most of all. By the end of the War of Independence in 1921 there would be over 7,000 Black and Tans and 1,500 Auxiliaries in the country.

Gen. Neville MacGready, GOC of the British army in Ireland, refused to take responsibility for the RIC, the Black and Tans or the Auxiliaries and openly condemned their acts of indiscipline. This friction between the military and the police was a major factor in Britain’s failure to implement an effective security policy during 1920. By October of that year the ‘king’s writ’ no longer ran in many parts of Dublin or the countryside. All British forces were now being concentrated in the towns, or at least in very strong barracks, obviously with a view to shortening the front. The IRA forces opposing them were becoming stronger and highly organised, albeit with little overall coordination from Dublin.

However, there was also little coordination between the RIC, the Black and Tans, the Auxiliaries and the regular British army. As a result, there was widespread hostility caused by the lack of control over the Tans and the Auxies, and it was often directed at any British official. Consequently, the military was torn between those who thought it best to ride out the storm, letting politicians negotiate a settlement, and those who advocated sterner measures to stamp out the IRA completely.

Neither the Tans nor the Auxies exhibited much in the way of military discipline, and the levels of violence and reprisals mounted daily. Their arrival and the brutality of their tactics drove many to support the IRA. What did the Black and Tans achieve? They served no purpose for the British government, as they failed to stop what the IRA was doing. They did, however, succeed in gaining the republican cause a great deal of civilian support simply because of their acts—people may not have joined the IRA, but they were supporters of it and gave what financial help they could to the movement.

The Black and Tans remained in Ireland until the Truce in July 1921, and the last of them left Ireland in 1922. More than a third of them left the service (or were killed) before they were disbanded along with the rest of the RIC—an extremely high wastage rate—and well over half received government pensions.

Joseph E.A. Connell Jr is the author of The shadow war: Michael Collins and the politics of violence (Wordwell Books).