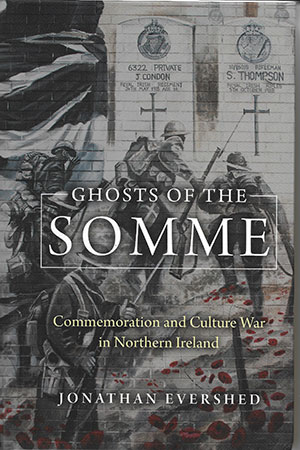

Ghosts of the Somme

Published in Book Reviews, Book Reviews, Issue 6 (November/December 2018), Reviews, Volume 26JONATHAN EVERSHED

Notre Dame Press

£43

ISBN 9780268103859

Reviewed by Brian Hanley

Brian Hanley is a research fellow at the University of Edinburgh.

Brian Hanley is a research fellow at the University of Edinburgh.

In contemporary Ireland, many see commemoration of the Great War as aiding reconciliation, hoping that the ‘shared human costs’ of the conflict might ‘transcend local Irish political sectarian differences’. As Jonathan Evershed notes in this original and provocative new study, however, this has meant that ‘criticism of the role of the British state … in the instigation and perpetuation of violence’ is ‘almost wholly absent from public discourse and the prevailing official narrative’. This applies as much to the Republic as to the North, but while commemoration of the war is now an all-Ireland affair it was already very significant for unionists in Northern Ireland.

Of all the sacrifices of that conflict, it is the Battle of the Somme, in which the 36th Ulster Division was decimated, that looms large in loyalist memory. As Evershed illustrates, however, while always an important part of loyalist iconography, it is in the last twenty years that the Somme has become central to local memorialisation. There is now far more emphasis on the Great War in loyalist communities than ever before. On wall murals ‘the once ubiquitous image of “King Billy”’ has been ‘almost totally usurped’ by that of the 36th Ulster Division. The Orange Order is declining in membership but the various Somme associations are flourishing. Bandsmen now often sport Great War-era uniforms. For many loyalists the experience of their ancestors a century ago is far more ‘real’ than that of the 1690s, one of Evershed’s interviewees noting that ‘it’s about ordinary guys from your street … it’s a bit more politically correct, if nothing else, than the conqueror on the horse’.

The author draws on a theoretical framework strongly influenced by Jacques Derrida and locates his work in debates about memory that may be difficult for the non-specialist, but most of the book is centred around interviews with those involved in loyalist commemoration and the author’s own experience of these commemorations. Evershed’s research was undertaken in the period that saw Brexit, the collapse of the power-sharing executive, the ‘flag’ controversy, a referendum on Scottish independence and the election of Donald Trump. He illustrates how the politics of language, culture and identity all deeply influence how people remember the past. What emerges is a picture of a community who feel themselves misunderstood, parodied and patronised. This is rooted in a long experience of deindustrialisation and dislocation, which has produced a sense of fatalism, many echoing the view that ‘We’re suffering at the hands of a culture war … none of our communities are experiencing the peace dividend that we were promised’.

It is important to note, as Evershed does, that most loyalists do not consider themselves to have ever benefited from the material and symbolic ascendancy of the Stormont era. Even the term ‘loyalist’ itself has distinct social connotations, one man suggesting that it is ‘perjorative … a classist term’ used about ‘Unionists who are prepared to be violent’. Indeed, after one commemoration, the Belfast Telegraph suggested that ‘to equate dead terrorists with the heroes who fought at the Somme … is to sully their memory’. At ground level, however, it is very often the UVF and the UDA (though no love is lost between them, in part because the UVF claim the lineage of ‘Carson’s army’) who mobilise around such events. There are a number of aspects to this. First, remembering the Great War allows loyalism to ‘plug itself into the biggest, most comprehensive, solemn ceremonial event’ in the United Kingdom: ‘from Shetland to Cornwall, everybody wears the poppy’. It is a reminder to the British and the Commonwealth that Ulster loyalism is part of their story too. Second, there is the rivalry with Irish republicanism, whose narrative, one loyalist sarcastically notes, ‘involves everything from Martin Luther King to Gandhi—with a few guns thrown in as well’. But ‘remembering the role of Ulstermen alongside soldiers from the rest of the world [gives] a sense of being part of a bigger story … gives you some kind of sense of dignity back’. There is also the reality that for many people it simply allows ‘reclamation of a family history which has never been properly commemorated’; ‘people wanna reach out and get a connection … This was their relatives’. Hence loyalist communities have seen re-enactments involving thousands in period dress, organised tours of battlefields in Flanders (in part facilitated by low-cost air flights) and all manner of local commemorations. Loyalists recognise but are uneasy about the ‘greening’ of Irish war commemoration because, after all, ‘it was a British war … at the end of the day they fought for the United Kingdom’. At the same time, some note how the conflict can be used to counter prejudice ‘when people begin to get on their high horse about Muslims … People forget they fought for the Empire as well … they deserve to be remembered, no matter what their religious affiliation’. Nevertheless, some commemorations are also an opportunity to express sectarian sentiment and for paramilitary mobilisation. While many obviously enjoy the re-enactments, one young loyalist suggests that ‘dressing up like toy soldiers … pretending to be someone from a hundred years ago: there’s something a bit sinister and a bit menacing and a bit morbid in it … I cringe actually’. (Perhaps those involved in similar republican commemorations might take note.) In general, loyalists are not critical of the war, seeing the sacrifice of the Ulster Division as ‘part of something glorious’. In contrast, one of Evershed’s interviewees asserted that the men at the Somme ‘were duped!’ and that for him was ‘the importance of the Somme … I don’t want to raise children in a community where they have to fight a war’. Written with empathy and a willingness to engage with views he often disagrees with, Evershed’s book provides a template that other scholars should follow as they interrogate the diverse commemorative agendas of our centenary decade.