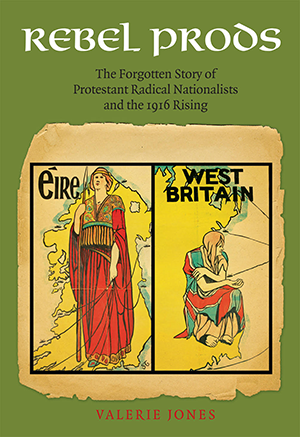

Rebel Prods: the forgotten story of Protestant radical nationalists and the 1916 Rising

Published in Book Reviews, Book Reviews, Issue 4 (July/August 2017), Reviews, Volume 25VALERIE JONES

Ashfield Press

€25

ISBN 9780995672208

Reviewed by: Sinéad McCoole

This book gives the reader much more than the subtitle suggests—the breadth of references span over 400 years, from a description of the alphabet and catechism in the Irish language in 1571 to references to the Irish Guild of the Church (Cumann Gaelach na hEaglaise) up to its centenary in 2014. In that expanse it does not lose its core objective: to provide the reader with a greater understanding of what came before the Rising and what came after.

This book gives the reader much more than the subtitle suggests—the breadth of references span over 400 years, from a description of the alphabet and catechism in the Irish language in 1571 to references to the Irish Guild of the Church (Cumann Gaelach na hEaglaise) up to its centenary in 2014. In that expanse it does not lose its core objective: to provide the reader with a greater understanding of what came before the Rising and what came after.

For over ten years Valerie Jones consulted archives and libraries and conducted interviews in order to complete her work and prepare biographies of 95 individuals (of whom 45 were selected for inclusion in this publication). The individuals surveyed not only come from the Church of Ireland but also include Presbyterians, Methodists, Unitarians, Plymouth Brethren, Moravians and those from a Quaker background. Some of these ‘rebels’ were stereotypical ‘Anglo-Irish upper class, privileged land-owning “horsey” types with English names and upper crust accents’, but there were many others who did not fit that description. Many were working-class. This book contains a variety of people described in the context of their participation in organisations such as the Irish Citizen Army, the Irish Republican Brotherhood and Cumann na mBan.

Valerie Jones explores the writings of these ‘Protestant rebels’ and the recurring question—could Protestants be accepted as truly Irish? While her book is focused on Protestant nationalists from 1890 to 1923, she gives examples of similar discussions for more recent generations. She quotes Graham Norton’s contribution to the 2007 BBC programme Who do you think you are?, in which Norton recalled his experience of growing up in Ireland:

‘As far as I know we were Irish as far as we go back. Irish, Irish, Irish, yet made to feel you were not Irish because you weren’t Catholic … made to feel slightly foreign in your own homeland … I’m Irish. I’m nothing else.’

This book owes its range and depth to the author’s lifetime of work, her fluency in the Irish language (she was educated at the Diocesan School for Girls and Coláiste Moibhí, which provided Irish-language teacher-training for Protestants) and her own participation in organisations such as the Cumann Gaelach na hEaglaise and her work in the Dublin diocese of the Church of Ireland. Over the years she sought out sources and constructed these life stories from fragments and footnotes.

One of the events explored is the gunrunning at Howth. Readers may be aware that the organisers, fund-raisers, crew and owners of the yachts were Protestant, but Valerie Jones gives a new cohesion to the story. The contribution to the language question of Protestants like Douglas Hyde, the son of a Church of Ireland rector, is well known. Detailed here are his plans for ‘de-anglicising Ireland’ and tracing back the Church of Ireland to Celtic times. His story is undergoing a new appraisal at this time. What is important about this book is that it does not tell his story in isolation but rather places him in the organisation alongside others who shared his religion.

Many of the prominent Protestant women—Countess Markievicz, Maud Gonne MacBride, Lillie Connolly—converted to Catholicism. Mabel McConnell FitzGerald (mother of Garret FitzGerald) was also a late convert. Her biography here is the fullest account of this interesting woman that I have read to date and is enriched by the late Dr FitzGerald’s memories as related to the author.

Valerie Jones also looks at the cult of martyrdom in the aftermath of the Rising—for example, how commemorative Masses were exploited by the widows of the dead leaders. It is ironic that the person who gathered much of the material culture of this period was a Protestant, Helen (Nellie) Gifford, the ‘only one of the Gifford sisters to take an active part in the Rising’. Unlike her sisters Muriel, widow of Thomas MacDonagh, and Grace, widow of Joseph Plunkett, Nellie did not convert to Catholicism and remained to the end, as Valerie Jones describes her, a ‘staunch’ Protestant. As recorded here, Nellie gathered material on the 1916 leaders for commemoration in the 1930s. I can add to this story. Not only did Nellie gather this material—Mass cards, scapulars, rosary beads—but she also organised its exhibition in the National Museum of Ireland during the Eucharistic Congress of 1932. I have often wondered whether this is the reason why there was so much material on display (up until the centenary in 2016) that related to Catholicism. The action of Nellie Gifford in the compiling of the ‘Easter Week Collection’, using the hook of a mass event for those of the majority religion in the country to ensure the safe keeping of key artefacts within a public collection, underscores the purpose and conclusions of this book on the role of ‘Rebel Prods’.

The author nurtured in her children a love of the past so strong that they became professional historians. Without them this book would never have been published. Valerie Jones’s vast archive was collated and prepared for publication from her handwritten research by her son Mark and her daughter Heather.

Sinéad McCoole is a historian, curator and member of the government’s Expert Advisory Group on the Decade of Centenaries.