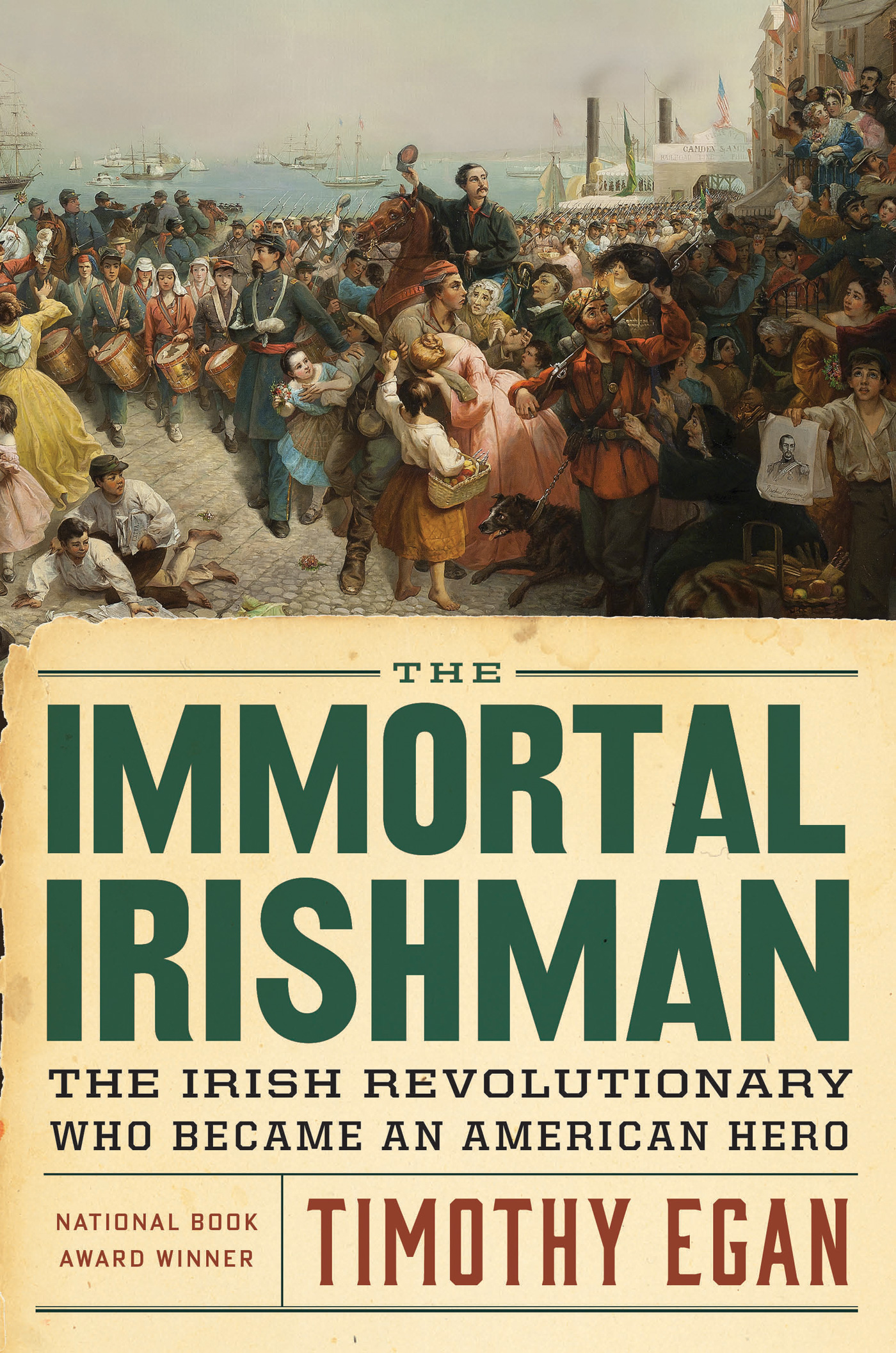

The immortal Irishman: the Irish revolutionary who became an American hero

Published in Book Reviews, Issue 5 (September/October 2016), Reviews, Volume 24TIMOTHY EGAN

Houghton Mifflin Harcourt

$28

ISBN 9780544272880

Reviewed by: Dean Jobb

Thomas Francis Meagher should have died in 1849, at the age of 25. A leader of the failed Young Ireland uprising, he faced the death penalty for treason. Offered a chance to speak before the sentence was passed, Meagher—a spellbinding orator—made a passionate plea for Irish independence:

Meagher’s sentence was commuted and he was banished to the distant penal colony of Tasmania. It marked the end of his dream of liberating his homeland but it was the beginning of a remarkable journey that would make him the most influential Irish-American of his time.

In The immortal Irishman, American author and journalist Timothy Egan brilliantly traces the remarkable and improbable life of an Irish legend: ‘The man was never quiet, never still, never slow, never far from history’s front edge’. Egan, a winner of the Pulitzer Prize and America’s National Book Award, proves as energetic as his subject. He scoured the historical record for the rich detail needed to breathe life into Meagher and his tumultuous times. And Egan is as eloquent and seductive on the page as Meagher was on the podium, combining bull’s-eye insights with vivid descriptions of people, places and events.

Meagher was an unlikely revolutionary. The son of a Waterford merchant who became a member of parliament, he could have enjoyed a life of wealth and privilege. But he was rebellious from the start; early clashes with his teachers evolved into an abhorrence of all things British. He was still a teenager when he resolved, as he put it, never to become ‘a silken and scented slave of England’.

He became, instead, England’s implacable enemy. He was one of the cadre of intellectuals—the Young Irelanders—radicalised by the horrors of the Great Hunger. With hundreds of thousands of his starving countrymen dead or forced to flee to America, Meagher rallied farmers armed with pitchforks and clubs to take on the military might of the British Empire. The uprising of 1848 was doomed, Egan writes—‘language and history against muskets, cannons and warships. An iron will … never beats an iron fist’.

Exile to the other side of the world marked a new beginning for Meagher; in Tasmania he was reunited with fellow Young Irelanders, married the daughter of a banished convict and plotted his escape. In 1852, after adventures worthy of fiction—at one point he was marooned on a deserted island, only to have a band of surprisingly generous pirates save him from starvation—he arrived in New York City.

America’s large and powerful Irish community embraced Meagher as a hero, his escape a symbol of defiance. He was praised and fêted and was in demand as a speaker and writer. Even President Millard Fillmore wanted to meet him. He wasted no time in applying for American citizenship and, after his wife died in 1854, he married a Fifth Avenue heiress who was almost as rebellious as he was.

Meagher’s new home was a nation divided over the scourge of slavery. The outbreak of the Civil War gave him a new mission—to reunite the fractured country that had given so many impoverished Irish immigrants a second chance. He supported Abraham Lincoln and raised a unit of Irish fighters. Battling the Southern rebels, he declared, ‘is the duty of us Irish citizens who aspire to establish a similar form of government in our native land’.

Even though he lacked military training, Meagher proved to be a brave and effective commander. Commissioned as a brigadier-general, he led his Irish Brigade into some of the bloodiest battles of the war. They became the Union’s shock troops, earning the respect of officers on both sides for their courage and toughness. ‘Never were men so brave,’ said Confederate commander Robert E. Lee. But respect came at a terrible cost—the Brigade was so decimated that it had to be disbanded in 1864.

Meagher fought on but his glory faded. The Civil War failed to produce the battle-hardened army he had hoped would liberate Ireland after the defeat of the South; too many Irishmen had been killed or maimed. Worse, the war exposed ugly divisions in Irish America. Many were unwilling to fight to end slavery, fearing that freed blacks would compete for jobs as labourers and servants. Irish resentment exploded in New York City in the summer of 1863, when anti-draft riots left as many as 500 dead.

Meagher’s stubborn support for Lincoln and the war effort made him an outsider in his own community. After the war he tried to make a new start as the acting governor of Montana. He made enemies as he struggled to bring order to the lawless territory and died in 1867, apparently the victim of foul play. ‘His vanishing is one of the longest-lasting mysteries of the American West,’ writes Egan, who makes a convincing case that he was the victim of murderous vigilantes.

‘His was a mind that needed the inspiration of great purpose,’ eulogised a childhood friend. ‘To see the great game of life played by other hands, and to stand by inactive, and only to watch … was to die a living death.’ Meagher was only 43 when he died, but his was a life for the ages. And with this elegant and riveting book, Egan has provided a fitting epitaph.

Dean Jobb is the author of Empire of deception (Algonquin Books, 2015).