The Royal Dublin Fusiliers in the Great War

Published in 20th-century / Contemporary History, Features, Issue 5 (Sep/Oct 2005), Revolutionary Period 1912-23, Volume 13

Royal Dublin Fusiliers pose for a recruitment poster.

The Soldiers Died in the Great War 1914–1919 (SDGW) series was first published in 1921 and was compiled from official casualty returns. Each regiment and unit in the British army that served in the Great War had its own listing of their dead. The lists contain the names of non-commissioned officers and men of other ranks only. Officers are listed in a separate publication, entitled Officers Died in the Great War 1914–1919 (HMSO, 1919). Part 71 of the SDGW series lists the men who died while serving with the Leinster regiment. Part 72 lists the Royal Munster Fusiliers and Part 73 lists the Royal Dublin Fusiliers (RDF). The latter lists each Dublin Fusilier’s name, rank, regimental number, place of birth, where he enlisted, occasionally where he lived (town and county), how he died (whether he was killed in action, died of wounds or died from disease, etc.), what theatre of war he died in (e.g. France and Flanders, Gallipoli, the Balkans (Salonika), etc.), and if he had previously served in another regiment prior to joining the ‘Dublins’. Further information may be obtained from the Commonwealth War Graves Commission (CWGC) listings on Dublin Fusiliers—the country where the man is buried or mentioned on a memorial and/or cemetery and grave number, and further information such as age and marital status, next of kin’s address, etc. If a man’s body were never found, his name would be inscribed on a war memorial near where he was killed.

Anomalies

The SDGW series gives the town and county in which the man was born. The CWGC data may also give the name of the street in which he or his next of kin—usually parents or wife—lived. In most cases both sources agree. For example, Pte Thomas Byrne of the 2nd RDF died of wounds on 27 August 1914. In the SDGW data he is listed as born in Drogheda, Co. Louth. However, in the CWGC data some further detail is given as to where in Drogheda he lived prior to enlistment. He is listed as being the son of Nicholas and Rose Byrne of 3 Boyne Place, Drogheda, Co. Louth. But there are anomalies and errors in both lists. There are Dublin Fusiliers listed in the SDGW but not in the CWGC, and vice versa. There are men listed in the SDGW with the same regimental number. Pte P. Campbell 17984 of the 2nd RDF has the same regimental number as Pte John O’Brien of the same battalion. This is explained by the fact that Campbell served and died of wounds on 15 October 1916 under the alias of ‘John O’Brien’. Sgt Henry Hare of the 5th RDF has the same regimental number (6745) as Pte Martin Walsh of the 2nd RDF. Nevertheless, by their random nature, the data and method of analysis do present a profile of the Dublin Fusiliers in terms of place of birth, age, etc.

Between 4 August 1914 and 11 November 1918, according to both the CWGC and the SDGW series, the total number of men who died while serving as Dublin Fusiliers was 4,858—281 officers and 4,577 men of other ranks. According to the official history of the 1st battalion of the regiment written by H.C. Wylly (Neill’s Blue Caps. The history of the 1st Battalion Royal Dublin Fusiliers, vol. III) the figure is 269 officers and 4,508 men of other ranks. The last recorded death in the CWGC data is that of Pte M. Callaghan, 7th battalion, aged 39, a married man who lived at 38 Old Bride Street, Dublin. He died on 6 August 1921 and is buried at Grangegorman military cemetery. For the purposes of commemoration, the Commonwealth War Graves Commission stopped recording service personnel who died as a result of the Great War on 31 August 1921. According to the CWGC, the total number of men who died while serving with the Dublins at the time of their death between 4 August 1914 and 6 August 1921 is 4,973—292 officers and 4,681 men of other ranks.

Nationality profile

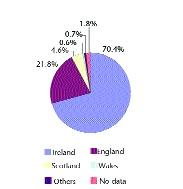

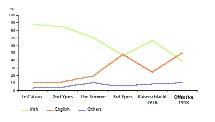

Closer analysis of the data indicates a variance in the nationality profile (Fig. 1) of the battalions with time. The Irish and non-Irish (mainly English) compositions varied in each battalion as the war progressed (Fig. 2). The 2nd battalion was a regular one that served from the beginning of the war to the end. In August 1914, 87.3 per cent of its members were born in Ireland and 9.1 per cent in England. These were men who enlisted before the war. Irish recruitment into the British army between 1910 and 1913 remained steady. In 1910 Irish-born soldiers comprised 9.4 per cent of the British army, and 9.1 per cent in 1913. These percentages closely match the figure for the Irish population of the United Kingdom between 1910 and 1913 (9.7). By 31 May 1915 the Irish percentage of the 2nd RDF had dropped slightly to 84.4, while the English percentage rose slightly to 11.2. One explanation as to why the Irish concentration remained reasonably high up to 31 May 1915 was that the ‘wastage’, a term occasionally used to describe casualties, was replenished by regimental reservists from the 3rd, 4th and 5th reserve and special reserve battalions.

Closer analysis of the data indicates a variance in the nationality profile (Fig. 1) of the battalions with time. The Irish and non-Irish (mainly English) compositions varied in each battalion as the war progressed (Fig. 2). The 2nd battalion was a regular one that served from the beginning of the war to the end. In August 1914, 87.3 per cent of its members were born in Ireland and 9.1 per cent in England. These were men who enlisted before the war. Irish recruitment into the British army between 1910 and 1913 remained steady. In 1910 Irish-born soldiers comprised 9.4 per cent of the British army, and 9.1 per cent in 1913. These percentages closely match the figure for the Irish population of the United Kingdom between 1910 and 1913 (9.7). By 31 May 1915 the Irish percentage of the 2nd RDF had dropped slightly to 84.4, while the English percentage rose slightly to 11.2. One explanation as to why the Irish concentration remained reasonably high up to 31 May 1915 was that the ‘wastage’, a term occasionally used to describe casualties, was replenished by regimental reservists from the 3rd, 4th and 5th reserve and special reserve battalions.

However, after the Battle of the Somme, when most of the reservists were used up, the Irish percentage dropped to 70.8 and the English percentage climbed to 19.4. This trend continued up to 31 August 1917, i.e. after the battalion’s part in the opening of the third Battle of Ypres (Passchendaele). Irish recruitment had dropped off drastically, and in order to keep the battalion up to strength the ‘wastage’ was made up mainly by Englishmen. Following the battle, the Irish concentration in the 2nd battalion began to rise and the English percentage to fall. This is explained by the fact that after the 16th (Irish) division’s part in Passchendaele (November 1917) the 8th and 9th (service) battalions of the regiment were disbanded and the men went into the 1st and 2nd regular battalions. After the German offensive in March 1918 and up to the end of the war in November, the Irish percentage of the battalion dropped off to 39.2 and the English percentage rose to 50.3. There were more English than Irish in the battalion by the end of the war. The decline in Irish representation in the regiment as the war progressed shows up in the service battalions as well (Table 1).

Irish provincial and English profile

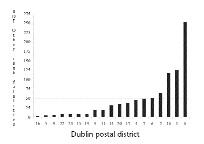

Fig. 3: Fatalities by Dublin postal district.

Dublin Fusiliers came from all of the 32 counties of Ireland. The highest proportion came from Dublin city and county. Of the 1,711 Dubliners who died, 1,409 or 82.3 per cent enlisted in Dublin. In Ulster the highest component came from County Antrim, the majority from Belfast. Fourteen of the Belfast Dublins who died came from the Shankill.

Of the 999 Englishmen who died while serving with the Dublins, the highest proportion, 327, came from Middlesex (London) (168) and Lancashire (159). Moreover, 441 or 44.1 per cent had previously served in other regiments. As shown in Fig. 2, using the 2nd battalion as an example, the percentage of Englishmen in the regiment rose as the war progressed. Among them were the two Evenett brothers, Albert and Alfred. Both came from Leytonstone and had previously served with the Wiltshire regiment before their transfer to the RDF. Their Wiltshire regimental numbers were 13054 and 13053 respectively. When transferred to the Dublins, their new regimental numbers were again together, 15356 for Albert and 15355 for Alfred. Albert went into the 7th RDF and Alfred into the 6th. Sadly, both men were killed. Albert was the first. He died of wounds as a lance sergeant in Gallipoli on 12 August 1915. Nearly one month to the day before the war ended, Alfred was killed in action on 10 October 1918.

Fig. 3: Fatalities by Dublin postal district.

Although Albert died of wounds and was probably buried, his body was never found and his name is on the Helles memorial to the missing of Gallipoli. Nor was Alfred’s body ever found; his name is on the Vis-en-Artois memorial in France.

Dublin city and county profile

The total number of other ranks who died with the regiment between 4 August 1914 and 11 November 1918 and born in Dublin city or county is 1,712. When cross-checked with the data contained in the CWGC, 888 gave details of an address in Dublin where he, his parents or next of kin lived (Fig. 3).

In order to examine what part of Dublin these men came from, the current Dublin postal district numbering system was applied to locate around the city and county the addresses given by the 888 soldiers for whom Dublin address data exist. Dublin 8 (mostly south side) had the highest proportion of the Dublin-born RDF fatalities, and Dublin 1 (north side) the second highest—both inner-city districts. In 1914 these were the poorest areas of the city, with dreadful tenement living conditions. According to a 1914 government report, out of a total Dublin population of 304,000, some 194,000 (63 per cent) could be reckoned as working-class. The majority lived in tenement houses, almost half with no more than one room per family. Approximately 37 per cent lived at a density of more than six persons per room. Fourteen per cent lived in houses declared unfit for human habitation. The only water supply for houses that sometimes contained as many as 90 people was often a single tap in the outside yard. ‘We cannot conceive’, wrote the committee who presented the report, ‘how any self-respecting male or female could be expected to use accommodation such as we have seen.’

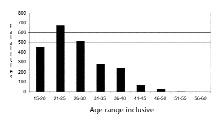

Fig. 4: Age range.

Of the non-tenement houses in which the rest of the working-class population lived, the report stated that some ‘scarcely deserve the name house, and could be more aptly described as shelters’. The death rate in Dublin was higher than in many other large centres of population in the United Kingdom, although it was highest of all in Wexford, Galway and Cork. The same report reproached Dublin Corporation over its housing commitments.

Many of the inner-city streets of Dublin city suffered more than their fair share of tragedy from the war. Eleven Dublin Fusiliers from Francis Street died, three from the Coombe. Brothers such as the three McDonnells from Bride Street, the two Gallagher brothers, Terrence and Christopher, from 63 Bridgefoot Street and the Murray brothers, John and Michael, from Hanover Parade died. Neighbours were killed. Pte Patrick Redmond from 3 Bishop Street and Lance Sgt Sylvester Mullen from next door at No. 4 were among the Dublin 8 statistics. Over the Liffey, seven Dublins from Gloucester Street added to the Dublin 1 statistics. Seventeen-year-old Pte Patrick Byrne was gassed at Hulluch and died on 27 April 1916. He lived at 19 Summerhill. A few weeks later in the same Hulluch sector Pte Patrick Doyle, aged 22, was killed. Patrick lived with his wife in the same house as young Pte Byrne, at 19 Summerhill. Judging by the data presented in Fig. 3, it seems that there was a link between poverty in Dublin’s inner city and recruitment into the Dublin Fusiliers. Of the men who came from Dublin 1 and 8, it is very difficult to separate the regular from the volunteer Kitchener/ Redmond recruits. When faced with a choice between poverty at home and the risk of death or incapacity fighting with the Dublin Fusiliers in France and Flanders, it would seem that some Dubliners chose the latter.

The third-highest Dublin postal district from which Dublins came was Dublin 18. In this postal area I have included Blackrock, Kingstown (Dún Laoghaire), Dalkey and Monkstown. In 1914 these districts had a high proportion of Protestants, who were more than likely to have unionist political sympathies. While generalisations are always risky, it would be reasonable to assume that living conditions were better in Kingstown than in a tenement house in the Liberties, which would imply that it might not have been solely for ‘the shilling’ that so many from Dublin 18 enlisted in the RDF.

Age profile

Cork solicitor Lt Bob Staunton—pictured here (extreme left) with his family—was killed at Gallipoli in August 1915.

The number of other ranks RDF fatalities for whom there are age details in the CWGC data is 2,272 (Fig. 4). The youngest recorded Dublin Fusilier who died was Pte Joseph Berrills of the 1st battalion, from Drogheda, Co. Louth. He died of wounds in Gallipoli on 22 August 1915. Joseph was fifteen when he died. The oldest recorded Dublin Fusilier who died was Pte Christopher Power of the 8th battalion. A married man and a native of Athy, Co. Kildare, Pte Power was 59 when he died on 28 April 1916 from gas wounds probably received at Hulluch. Recruits were supposed to be between 19 and 45 years of age. One interesting feature of the 15–20-year-old fatalities is that amongst their number are 34 lads who were seventeen years of age when they died, i.e. under the minimum recruiting age. Pte Timothy Kiely, 1st RDF, from Cork Hill, Youghal, Co. Cork, was killed in action on 29 March 1918 aged seventeen. Not only did the army take in men who were over age, it seems that they knowingly also took young lads who were under age, even as late as March 1918. The highest fatalities occurred amongst the 21–25 age group, the vast majority of whom, 90 per cent, were unmarried men.

Conclusion

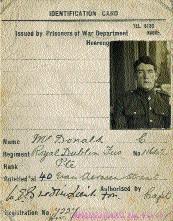

Before he enlisted, L/Cpl John Boland was a messenger boy from Russell Street facing Croke Park in Dublin. He was killed on 27 August 1914 near the French village of Clary. Born in Holles Street maternity hospital, Dublin, Pte Christopher McDonald was a gardener’s assistant who lived in Rathfarnham. He was captured near Clary and spent the rest of the war in a German POW camp. Pte Thomas Errity was a farm labourer from Newtownmountkennedy, Co. Wicklow. He was killed in Gallipoli in April 1915. Sgt Paddy Cummins of the 6th Dublins was a baker from Pearse Street. He survived the war to rear a family, one of whom became a Fianna Fáil TD and served under Taoiseach Seán Lemass. Lt Bob Stanton was a solicitor from Cork. He died in Gallipoli in August 1915, fighting with the 6th Dublins. Lt Tom Kettle, born in Artane in north County Dublin, was a professor of economics at University College Dublin. Sgt Andrew Kinsella from Arbour Place in Dublin was a postman and was married with a young family. He was killed during the German March offensive of 1918. Fr Willie Doyle SJ was a chaplain to the Dublins.

Pte Christopher McDonald, a gardener’s assistant from Rathfarnham, Co. Dublin, spent most of the war in a German POW camp.

He came from Dalkey and was killed at Frezenberg ridge near Ypres in August 1917. Sgt Tommy Cunningham was a decorator before he enlisted. He came from a tenement house in Peter Street and survived the war. Captain Harvey de Montmorency, an officer in the 7th Dublins, thought that the Irishmen in his battalion came from ‘the poorest, unskilled casual labourers of Dublin, the lowest strata of our society’. This is an over-simplification. It seems that the Dublin Fusiliers who served and died in the Great War were a group of men, mainly Irishmen in their mid-twenties, who reflected the society from which they came, a society with all its divides of class, wealth, religion and politics.

Tom Burke MBE is chairman of the Royal Dublin Fusiliers Association.

Further reading:

Soldiers Died in the Great War 1914–1919, part 73 (Royal Dublin Fusiliers) (London, 1921).

Stand To, journal of the Western Front Association, no. 27 (1989).

The Irish Sword, journal of the Military History Society of Ireland, nos 66 (summer 1987) and 81 (summer 1997).

Commonwealth War Graves Commission, www.cwgc.org.

Royal Dublin Fusiliers Association, www.greatwar.ie.