Sisters sentenced to death: infanticide in independent Ireland

Published in 20th Century Social Perspectives, 20th-century / Contemporary History, Features, Issue 6 (Nov/Dec 2011), Volume 19 The County Roscommon district courthouse was crowded in January 1935 when sisters Elizabeth (23) and Rose E. (18) were tried for the murder of the elder sister’s infant daughter. Like most of the mothers who stood trial for infanticide in post-independence Ireland, Elizabeth was unmarried. Irish society was deeply intolerant of unmarried mothers and their illegitimate children in the 1930s and the experience of single motherhood was a huge ordeal for many unmarried women. The options available to poor, single women at the time were extremely limited; many felt that they had no choice but to give birth in secret and to take the infant’s life shortly after delivery. The investigation into the disappearance of Elizabeth’s baby began over three months prior to their appearance at the district court, in mid-October 1934. The following month, although the neonate’s body had still not been located, the sisters were formally chargedwith murder. Elizabeth E. was one of 183 single women who stood trial for the murder of an illegitimate newborn at the Central Criminal Court between 1922 and 1950; Rose was one of eight women who stood trial for the murder of an unmarried sister’s illegitimate infant.

The County Roscommon district courthouse was crowded in January 1935 when sisters Elizabeth (23) and Rose E. (18) were tried for the murder of the elder sister’s infant daughter. Like most of the mothers who stood trial for infanticide in post-independence Ireland, Elizabeth was unmarried. Irish society was deeply intolerant of unmarried mothers and their illegitimate children in the 1930s and the experience of single motherhood was a huge ordeal for many unmarried women. The options available to poor, single women at the time were extremely limited; many felt that they had no choice but to give birth in secret and to take the infant’s life shortly after delivery. The investigation into the disappearance of Elizabeth’s baby began over three months prior to their appearance at the district court, in mid-October 1934. The following month, although the neonate’s body had still not been located, the sisters were formally chargedwith murder. Elizabeth E. was one of 183 single women who stood trial for the murder of an illegitimate newborn at the Central Criminal Court between 1922 and 1950; Rose was one of eight women who stood trial for the murder of an unmarried sister’s illegitimate infant.  It wasn’t the first time the County Roscommon sisters had fallen foul of the law; in December 1933 they had been convicted of the larceny of three turkeys. On that occasion they had been discharged. This time, however, they faced the death penalty if convicted. Garda John Salmon was present when Superintendent Twomey arrested and charged Elizabeth and Rose E. with murder in their parents’ home. They said nothing in reply. At one point Garda Salmon was alone in the kitchen while the sisters were dressing in the parlour. He recalled how they left the door open while they combed their hair and put their caps on. Garda Salmon took note of the conversation he overheard between them. The sisters seem to have been shocked and confused. Lizzie apparently said ‘What did he say we did—murder the child?’ Rose responded by saying ‘Does he think we are idiots?’ Lizzie then repeated the word ‘murder’, while Rose responded by saying ‘Let them murder away’ (National Archives of Ireland, Court of Criminal Appeal, 13/1935).

It wasn’t the first time the County Roscommon sisters had fallen foul of the law; in December 1933 they had been convicted of the larceny of three turkeys. On that occasion they had been discharged. This time, however, they faced the death penalty if convicted. Garda John Salmon was present when Superintendent Twomey arrested and charged Elizabeth and Rose E. with murder in their parents’ home. They said nothing in reply. At one point Garda Salmon was alone in the kitchen while the sisters were dressing in the parlour. He recalled how they left the door open while they combed their hair and put their caps on. Garda Salmon took note of the conversation he overheard between them. The sisters seem to have been shocked and confused. Lizzie apparently said ‘What did he say we did—murder the child?’ Rose responded by saying ‘Does he think we are idiots?’ Lizzie then repeated the word ‘murder’, while Rose responded by saying ‘Let them murder away’ (National Archives of Ireland, Court of Criminal Appeal, 13/1935).

Found guilty and sentenced to death

The sisters stood trial at the Central Criminal Court in Dublin in March 1935. After an hour’s deliberation the jury returned a verdict of guilty with a strong recommendation to mercy. Nevertheless, less than a month later, on 17 April, both sisters were sentenced to be hanged. Neither sister manifested any emotion when Mr Justice O’Byrne donned the black cap and passed the sentence of death, first on the elder sister and then on Rose. Juries in post-independence Ireland invariably recommended mercy for women convicted of infanticide and judges always strongly supported such recommendations. Between 1922 and 1950 twelve women and one man were convicted of the murder of an illegitimate infant in the southern state. Of the twelve women convicted of murder, nine were the birth mothers. In all cases the death sentence was commuted to penal servitude for life. Elizabeth and Rose would have to wait almost two months, until after the appeal, before learning that they would not be executed. Life imprisonment, however, was an unreality; Rose spent just over two years in prison and was released on licence on 1 December 1936. It is not known how long the elder sister spent in prison.

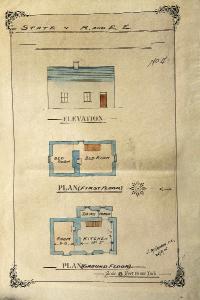

Gardaí carrying out their investigation at the house. Despite extensive searches of the surrounding countryside and the dragging of the river in the vicinity, no trace of the infant’s body was ever found. (National Archives of Ireland)

The County Roscommon case was more complex than most infant murder cases tried between 1922 and 1950. First, despite extensive searches of the surrounding countryside and the dragging of the river in the vicinity, no trace of the infant’s body was ever found. It was not uncommon for investigations to begin before a body was located in post-independence Ireland. Many suspected cases of infanticide were investigated by the gardaí because of ‘information’ they received from members of the public. The sexual behaviour of single women, particularly those living in tight-knit rural communities, was closely monitored. The gardaí pursued rumours about single pregnant women. Members of the neighbourhoods and communities in which unmarried pregnant women lived frequently played a key role in alerting the police about suspected cases of infanticide. It is apparent that while neighbours or acquaintances, on noticing that a single woman was pregnant, did not, in most instances, offer any advice or support, they were quite prepared to alert the police as soon as they suspected that the woman had given birth and no baby had appeared. Nevertheless, unlike the County Roscommon case, the infant’s body was almost always discovered before the case went to trial.

Sisters stuck to their story

Second, neither sister changed her version of events, despite the intense pressure of the trial at the Central Criminal Court, followed by an appeal hearing and the death sentence being upheld after the appeal. This was most unusual. Women who stood trial for the murder of an infant born outside wedlock often broke down as soon as they were arrested and charged. Few women seem to have made sustained attempts to deny that they had given birth or to lie about their crime; most seem to have broken down soon after being interrogated. Few seem to have thought of convincing lies to tell the authorities in advance of their arrest. This suggests that even if the women who feature in the trial records had planned to kill the infant from the outset they had not considered the consequences of such actions; some simply may have wanted to dispose of the problem, the shame of having a baby outside wedlock, as quickly as possible.

Although Rose claimed to have dug a grave for the infant near their home, the hollow she showed investigating gardaí was empty. (National Archives of Ireland)

In another case involving two sisters, the birth mother’s sister Cáit eventually told gardaí that her older sister Máire had killed her newborn infant. Both sisters were questioned separately by gardaí until 1am in February 1941. Cáit had probably been interrogated for several hours before she incriminated her sister. When she was asked ‘Cé agaibh a rinne é?’ (Which of you did it?), according to Garda Michael Ó Riada ‘Dúirt si Máire’ (She said Máire). ‘Thachtaigh sí é lena lámha ar a muinéal’ (She choked it with her hands on its neck) (NAI, Central Criminal Court, Co. Galway, 1941). Unlike Cáit ní C., however, Rose E. did not yield to such pressure, remaining loyal to her sister throughout the investigation and during the trial. In fact, Rose displayed considerable spirit and defiance when questioned. When asked how she buried her sister’s baby, Rose retorted, ‘Well it wasn’t with my face. It was with a spade’ (NAI, CCA, 13/1935). She never revealed where she had buried the baby, despite having been put under considerable pressure by the authorities. The sisters also seem to have been aware of their rights at a time when most of the women who appear in the trial records seem to have been ignorant of their rights during the pre-trial process. Very few would have had access to legal counsel during questioning. Yet when Sergeant Tobin began to look around the E. home on 30 October Lizzie reminded him that he was not entitled to search the house without a warrant. The following day Lizzie refused to sign a statement. She said that she would not sign it as she didn’t know what she was saying; she was, she claimed, nearly ‘gone in the head’ (NAI, CCC, Co. Roscommon, 1935). Gardaí had been searching their home and the surrounding areas for several days at that stage.

Established facts

The sisters’ explanations for the death and disappearance of Elizabeth’s baby were dismissed by one judge as ‘a tissue of falsehoods’. Certain facts have been established, however. Shortly before Elizabeth gave birth the sisters informed their parents and brother that Elizabeth was not in good health and needed to be hospitalised. At approximately 11pm on the night of 2 October 1934 the sisters called to the home of a local doctor, who drove them to the Roscommon County Home, where Elizabeth gave birth to a baby girl, Mary Teresa. Elizabeth wore a wedding ring when she was first admitted and told staff that her name was Mrs M. It was only when one of the nurses remarked that she did not know any Mrs M. in the area that Elizabeth admitted that she was unmarried. Such was the sense of disgrace associated with unmarried motherhood in Ireland during this period that when unmarried expectant women entered the union workhouse or a county home they generally lied about their marital status and registered as married women. Perhaps they may have hoped that by giving a false name they would escape detection after being discharged. Approximately two weeks later, Elizabeth returned to her parents’ cottage by car, accompanied by Rose. Elizabeth claimed that when she got out of the car she put her coat around her infant daughter and left her in a small grove of trees before entering her parents’ home. She did this because her mother was in the house at the time. Although the sisters insisted that they brought the baby upstairs to the bedroom they shared ten or fifteen minutes later and that the infant died the following morning, it seems likely that the baby was never brought into the house. In court, Elizabeth asserted that her infant daughter had been delicate from birth. She claimed that the morning after allegedly returning to her parents’ home she ‘lifted up the child’ but ‘could find no breathing in it’. She said that she ‘cried [her] fill and held it in [her] arms’. Elizabeth then asked her sister Rose to bury the baby’s body (NAI, CCA, 13/1935). Although Rose claimed to have dug a grave for the infant near their home, the hollow she showed investigating gardaí was empty. She was unable to account for the fact that the baby’s body was no longer there.

Interior of a Dublin Magdalen laundry in the 1890s. In post-independence Ireland single mothers would continue to appear before the courts on murder of infant charges, providing a steady stream of ‘sinners’ to Ireland’s network of Magdalen laundries. (British Library)

While some single expectant women, like Elizabeth E., found allies in a relative, others feared how family members would react. Most defendants felt unable to confide in anyone. They did their best to conceal signs of pregnancy from everyone they knew, perhaps even denying the pregnancy to themselves. They usually gave birth unattended. Some women found themselves homeless towards the end of pregnancy; a small number were forced to deliver unassisted in unsanitary conditions outdoors. Many Irish families reacted angrily to the news that an unmarried female relative was pregnant. A considerable number of single women in the case files seem to have come under sustained pressure from their relatives to kill their illegitimate infants and to conceal all evidence of their existence from the wider community. Some were turned out of the family home, only being allowed to return if they came back without the baby. Fear of male relatives’ discovery of an out-of-wedlock pregnancy seems to have been a motivating factor in many infanticide cases. It may well have been a motivating factor in the Roscommon sisters’ case. In October 1934 Rose E. remarked to her sister Elizabeth that ‘the old fellow will kill us if he hears about the baby’ (NAI, CCA, 13/1935). Such fears were articulated by a number of women in the cases examined.

High-profile case

The case involving the Roscommon sisters was but one of hundreds of murder of infant and concealment of birth cases involving a single mother that went before the courts in Ireland during the first half of the twentieth century. Unlike most infanticide cases involving single mothers, which received only passing mention in the national press, theirs was a high-profile case that attracted more interest than most. Many Irish people had followed the sensational case of the sisters from their trial at the Central Criminal Court through to the appeal and the overturning of the death sentence. There was a palpable sense of relief when the death sentence was overturned in May 1935. In that month the Irish Times suggested that all Ireland ‘is lighter in spirit at the news that the two sisters who were condemned to death for the murder of an illegitimate child have been reprieved’. There was a sense of unease that the birth mother and her younger sister could hang while the father of the deceased infant escaped ‘scot-free’. Outraged readers, in letters to the Irish Times, decried the death penalty, with one noting that ‘if our rulers really do hang these two girls it will be a sign that Ireland is sinking in the scale of civilisation’ (Irish Times, 20 May 1935). Although none of the women, or men, convicted of the murder of an illegitimate infant were executed in post-independence Ireland, many more would be convicted of manslaughter or concealment of birth. Most unmarried women convicted of these lesser offences would be sent to convents rather than to prisons. Judges who tried infanticide cases in post-independence Ireland seem to have felt that convents, or the Bethany Home in the case of Protestant women, were the most appropriate places of detention for unmarried women who had sinned by becoming pregnant outside marriage. Little is known about the fate of single Irish women who were convicted of the murder, manslaughter or concealment of birth of an illegitimate infant following their terms of incarceration. Some women’s relationships with their close relatives may have been ruptured following their arrest, trial and imprisonment, and they may not have returned to their parents’ home when they were released from prison, while others may have been welcomed back into the family fold. At yet another infanticide trial involving a single mother at the Central Criminal Court in June 1935, the judge referred to the ‘awful plague of infanticide which was over-running the country at the present time’. Single mothers would continue to appear before the courts on murder of infant charges for some time to come, providing a steady stream of ‘sinners’ to Ireland’s network of Magdalen laundries. HI

Clíona Rattigan’s What else could I do? Single mothers and infanticide, Ireland 1900–1950 has just been published by Irish Academic Press.

Further reading:

D. Ferriter, Occasions of sin: sex and society in modern Ireland (London, 2009).M. Luddy, Prostitution and Irish society, 1800–1940 (Cambridge, 2007). L. McCormick, Regulating sexuality: women in twentieth-century Northern Ireland (Manchester, 2011).