Monday 1 August 1932: Ireland’s finest Olympic hour?

Published in 20th-century / Contemporary History, Features, Issue 4 (July/August 2012), Volume 20

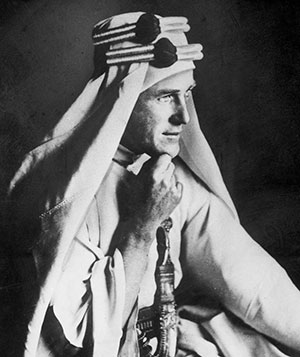

Opposite and right: The menu of a dinner to celebrate the return of Ireland’s conquering Olympic champions, Pat O’Callaghan (top left) and Bob Tisdall (top right) on 27 August 1932—signed by them and, amongst others, Éamon de Valera, W.T. Cosgrave, Eoin O’Duffy and Alfie Byrne. (Larry Ryder)

Bob Tisdall, from Nenagh, Co. Tipperary, had established a reputation as a great all-round athlete as an undergraduate at Cambridge University in the years leading up to 1932. In April of the Olympic year he had written to General Eoin O’Duffy, then the top man in Irish sports organisation, asking to be considered for selection in the 400m hurdles, an event in which he had never competed! O’Duffy liked his style and it was arranged that he would run a trial at Croke Park on 3 June. Tisdall quit his job and moved with his wife into an old railway carriage in Sussex. He had no track and only very basic facilities.

Last-minute addition to the team

At the trial in Croke Park Tisdall was faced with only one other competitor, a high hurdler who agreed to run just to make it a contest. Tisdall did not perform well, his 56.2 seconds falling far short of the standard laid down by the National Athletic and Cycling Association (NACA), which was the 55-second Irish record of Johnny Gibson, set at the Tailteann Games in 1928. O’Duffy, however, ordered a further trial, and on 18 June at the same venue Tisdall came home in a time of 54.2 seconds—a good but not outstanding performance. It was enough for O’Duffy, however, and he prevailed on the other selectors to add Tisdall to the team.Tisdall trained for a fortnight at Ballybunnion and then set off with the rest of the team on 3 July, arriving on 17 July in Los Angeles, where he went into virtual seclusion, spending most of his time relaxing and doing very little hard training. Following victory in the heat and semi-final of 31 July, the scene was set for the final on the following day, the field including the reigning and preceding champions in Taylor and Lord Burghley, and the current champions of the USA, Sweden and Italy, with Tisdall the avowed novice.

The final

The final

Drawn in lane 3, Tisdall got a clean start and immediately took charge of the race. He was first at the first hurdle and cantered away around both bends. He was well clear at the penultimate hurdle, but as he rose for the final barrier his technique let him down and he struck the hurdle quite hard. Unlike modern hurdles, which, though counterweighted, are designed to topple away from the runner, those in Los Angeles had an inverted T-shaped base, which meant that when hit they actually kicked slightly upwards in falling. While he didn’t actually fall, Bob’s rhythm was upset and he stumbled for a couple of strides, which allowed his opponents to close the gap. Hardin led the charge but Tisdall managed to gather himself again and crossed the line in 51.7 seconds, with Hardin in second place in 51.9 seconds. Morgan Taylor took the bronze medal. Tisdall’s time was a world record but because he’d knocked over the final hurdle it didn’t count. So Glenn Hardin received credit for the new world and Olympic record despite being the runner-up. Apart from the sheer brilliance of Tisdall’s performance, it is staggering to think that this race was actually only his fifth run over the full hurdle distance and that he had been a last-minute addition to our Olympic team (a portent of what was to happen to Ronnie Delany in 1956).

Pat O’Callaghan, defending Olympic hammer champion

Amazingly, immediately after his race, Tisdall quickly shook off the hordes of pressmen and made his way across the Los Angeles Coliseum to the vicinity of the hammer circle. His team-mate Dr Pat O’Callaghan was trying to retain his own Olympic title, which he had won in Amsterdam four years previously, but was in trouble because the surface of the circle was incompatible with his spiked shoes. He had acquired a file and with Tisdall’s assistance he was trying to smooth down the spikes as the competition proceeded. ‘The Doc’, as he was known, had come into the contest as joint favourite with Porhola of Finland, based on their sharing of the best throw of the year to date, and while O’Callaghan had the benefit of his earlier championship title the Finn was no mean competitor, having been Olympic shot-put champion in 1920 and a prominent performer in all the weight events. He had been away from competition for a few years before returning in a ‘new’ discipline.O’Callaghan had won his Olympic title in his main event in Amsterdam, even though he was at the time a relative novice at hammer-throwing. His win then was the first occasion on which the Irish tricolour was raised at an Olympic victory ceremony, all previous Irish-born champions having either represented other countries or, in the case of 1906, the actual Olympic Games having been the subject of dispute. The Doc was a renowned all-round athlete himself, albeit with emphasis on the weight events, recording high jump clearances of 6ft 2ins and 6ft 3ins in July 1930, while weighing around sixteen stone (100kg)!

Not happy with the throwing circle

In Los Angeles he was well experienced and had thrown close to the European record the previous year. After two throws in the preliminary rounds, however, he was lying only fifth, but he drew on his experience and managed 171ft 3.5ins to move into second place behind Portola’s 171ft 6.5ins. He was not happy with the throwing circle: his spikes were catching in the surface and interfering with his normal technique, so as the competition proceeded he was busily filing down the long spikes to allow him a smoother transition. He was grateful for Bob Tisdall’s help in this activity since he had to keep himself active and supple for the later throws.The first round of the final throws produced no major change but Zaremba of the USA moved into third place with 165ft 1.5ins and O’Callaghan threw about 170ft. The second final round showed no change, and going into the last round the Doc had only one chance left. His shoes would have to do now. The crowd was apprehensive as he stood in the circle and began his preliminary swings. Gradually increasing the speed of the hammer, he moved into his turns across the circle, one, two, three, and then lift and release. The hammer soared towards the sky and completed its arc, breaking the green turf at a distance of 176ft 11ins, probably beyond Porhola’s ability. And so it proved. Porhola threw well short of his own best mark in the final round, so gold was O’Callaghan’s yet again.And so, within a single hour, little Ireland had beaten the best in the world on the Olympic stage in two disparate events, possibly the greatest day in Irish sports history. HI

Kevin Byrne is a former insurance official.