Irish Credit Unions: a success story (3:1)

Published in 20th-century / Contemporary History, Features, Issue 1 (Spring 1995), Volume 3Anthony P. Quinn

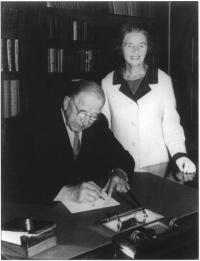

President De Valera signing the Credit Union Act in 1966;

with Nora Herlihy.

(Courtesy of The Irish League of Credit Unions)

A credit union is a mutual society, owned and run by the members on a democratic co-operative basis to provide a savings and loan service. Co-operation, a basic human process, was expressed in the traditional Irish meitheal by which neighbours helped one another with the harvest. The origins of modern formal co-operation were in the self-help movements of the Victorian era, which took different forms in various countries.

Agricultural credit societies—land banks

The growth of the Irish co-operative movement, mainly in the agricultural and creamery sectors, during the late nineteenth and the early twentieth centuries has been well documented and described (see HI Winter 1994). The main leaders were Sir Horace Plunkett, George Russell (Æ), and Fr. Tom Finlay SJ. Plunkett’s aims of better farming, better business and better living were effected under the aegis of the Irish Agricultural Organisation Society (IAOS). His ideals were translated into practical initiatives. The Plunkett Foundation in Oxford was established in 1919 to promote co-operative education and research.

Other projects under Sir Horace Plunkett’s leadership included setting up agricultural credit societies, usually called village banks or land banks. They were registered with the Registrar of Friendly Societies as specially authorised societies. That specific initiative, spearheaded by Fr. Tom Finlay SJ, was based on the Raiffeisen societies of southern Germany where small farmers associated to provide purchasing power for the mutual advantage of all participants. Weaknesses in the land banks included insufficient deposits to match loans, a dependency on state support and inadequate control procedures. The so-called land banks, however, did fill a void in rural Ireland.

The success of the Doneraile bank, founded in 1894, encouraged the IAOS to start similar societies. At the turn of the century, there were seventy-six land banks and the total reached 268 by 1908. Rural communities were rescued from the grip of the gombeen men, ruthless local shopkeepers who exploited small farmers by loaning money at exorbitant interest rates. Commercial banks had not served the credit needs of poor rural communities.

The land banks were run on a voluntary communal basis. Interest rates were low as the people themselves provided the source of credit by their savings. An inhibiting factor was reluctance to disclose personal affairs to local committees composed of neighbours and possibly the parish priest. Although there were differences in emphasis and detail, the land banks were a prototype for modern credit unions.

Folk High School,Red Island holiday camp, Skerries,County Dublin, May 1957

(Courtesy of Eilis Mac Eoin)

Lessons of failure and decline

World War One affected the land banks as support from the Department of Agriculture and Technical Instruction and from the Congested Districts Board declined due to government financial constraints. Many of the land banks emerged much weakened from the Great War. Commercial banks, realising the market potential, began to take a more active role in providing loans to smallholders.

The agricultural credit societies did not live up to the high expectations of their founders and became virtually extinct by the 1950’s. The societies did not survive into modern Ireland but they provided a Raiffeisen-type basis for credit union ideas and salutary lessons in pitfalls to be avoided. The lack of success associated with the land banks reinforced prejudices against co-operative credit. The Irish Banking Commission in 1938 concluded that there was little prospect that any useful development of co-operative agriculture credit could be achieved by state initiative. Economic Development, the blueprint for the modern Irish economy prepared by the Department of Finance in 1957, was presumably influenced by the land bank experience when it asserted that Irish history afforded no support for the belief that co-operative credit societies could be successfully established.

Friendly societies

Mutual loan and insurance societies were an expression of the self-help ethos of Victorian Britain. In Ireland, according to contemporary reports, there was a reluctance to use small savings banks and friendly societies. The small savings habit was not widespread but some farmers hoarded cash. Friendly societies were organised among the emergent urban working classes especially the better-off skilled tradesmen in the East and North East. Irish friendly societies developed in different forms and some societies called ‘tontines’ divided their funds among members at Christmas.

Societies like the Irish National Foresters and the Ancient Order of Historians provided mutual insurance on a wide scale before the modern welfare state. A small residue, including some specially authorised loan societies survived into the late twentieth century. The very successful St Mary’s Credit Union, Navan, County Meath, was founded in 1963 in the front room of the old Foresters’ hall in the town. In general, however, the friendly society movement lacked deep roots in Ireland and had only a minimal influence on the modern Irish credit union movement.

Social and economic studies

After the Second World War, concerned individuals stimulated the study of economic problems within a wider social and philosophical context. In 1946, extension lectures were organised by Professor Alfred O’Rahilly in University College Cork. In A Labour History of Ireland 1824-1960 (1992), Emmet O’Connor ascribes the UCC initiative to Catholic social teaching and trade union fear of communist and other secular influences.

An evening diploma course in social and economic studies at University College Dublin in the late 1940s/early 1950s, was directed by Fr. Edward Coyne SJ, President of IAOS. The UCD extra mural course was an innovation in Irish adult education aimed at people who normally would not have had access to third-level qualifications. As such the initiative was supported by the Congress of Irish Unions, part of a divided Irish trade union movement which also included the Irish Trade Union Congress.

In the UCD course, ethics and sociology lecturer, Cornelius Lucey of Maynooth, and later bishop of Cork, related the Victorian Rochdale co-operative principles to Christian social teaching on human dignity and State subsidiarity. The concept of the State supplementing but not supplanting private effort for the public good reinforced co-operative ideas. Dr. Lucey stressed the practical value of the course and exhorted the students to put theories into practice.

Muriel Gahan(Irish Countywomen’s Association), Sean Forde and Seamus Mac Eoin (co-founders of the Irish Credit Union movement) at the unveiling of Nora Herlihy’s portrait in 1988.

(courtesy of The Irish League of Credit Unions)

Ideas into action

One participant on the UCD diploma course, a civil servant named Seamus P. Mac Eoin, was inspired to form an economics study panel to debate topical social issues. Mac Eoin spoke on the co-op movement at a open meeting on 9 December 1953 at 35 Lr. Gardiner Street, Dublin, where the printers’ trade union was based. The paper stimulated interest in credit co-ops among a keen audience including Nora Herlihy, a Cork-born school teacher based in Dublin. She was later acknowledged as the founder of the Irish credit union movement along with Mac Eoin and Sean Forde.

Following the economics panel meeting an initiative was taken to tackle unemployment and emigration through worker co-op development and low cost credit. That was topical because 1954 was the centenary of the birth of Irish co-op pioneer, Sir Horace Plunkett, and also of Alphonse Desjardins, Canadian pioneer of the caisse populaire, a prototype for modern credit unions. The Dublin Central Co-op Society (DCCS) held its first meeting on 6 March 1954 in Moran’s Hotel, Talbot Street, Dublin. The DCCS, whose registered office was at 85 Lr. Abbey Street, formed an investment bank but its legal basis was not clear and further research was necessary. Nora Herlihy obtained data on credit unions from the Credit Union National Association (CUNA), Madison, Wisconsin, USA.

John Hume – spearheaded the spread of the credit union movement in Northern Ireland in the 1960s. (Peacemaker)

Credit Union Extension Service

Despite the demise of the land banks, the concept of co-op credit was re-discovered and developed in the late 1950s by this small group of Irish enthusiasts. The leaders—Nora Herlihy, Seamus MacEoin and Sean Forde—started a ginger group, the Credit Union Extension Service in 1957. Community groups including Muintir na Tíre, the National Farmers’ Association (now IFA), and the Irish Countrywomen’s Association (ICA) were represented. The National Co-operative Council, under its president Brendan Ó Cearbhaill, a printers’ trade union leader, was also active in promoting mutual societies. The initiative aimed to create a reliable system of low cost credit for urban workers and rural communities in an expanding market for consumer goods. There was also a charitable element in rescuing poorer people from the moneylenders’ trap. There was large middle class participation in the organisation and membership of credit unions.

Folk high schools

By 1958, the first Irish credit unions were at Donore Avenue, South Circular Road, Dublin, where Eileen and Angela Byrne (Ní Bhroin) were the pioneers and at Dún Laoghaire. The latter was confined to members of Dún Laoghaire Grocery Co-op, managed by Eamonn Quinn. The Dún Laoghaire Co-op stimulated community initiatives including the Borough Historical Society and an all-Irish school. Eamonn Quinn and his brothers operated Red Island Holiday Camp, at Skerries, north County Dublin, where folk high schools, termed Daon Scoileanna, were organised on the Danish model in the 1950s and early 1960s.

Themes discussed at the resid-ential folk schools included co-operation and community development. In May 1957, a folk school organised at Red Island by the National Co-operative Council under its chairman, Brendan Ó Cearbhaill, was opened by An Taoiseach, Eamon de Valera. John O’Halloran, manager of Red Island, was active in the Co-operative Council. The director was Con Murphy, an Irish Sugar Company executive and admirer of the folk high schools founded by Grundvig in Denmark to promote community development. Those folk high schools provided the basis for the successful Danish and Scandinavian co-operative movements. As an educational aid, an American credit union film, named King’s X to recall the marking of debtors’ doors before imprisonment, was shown at the Skerries folk school in 1957. The innovative audio-visual aid helped to spread the fledgling credit union message.

International connections

The film was supplemented by an address from Nora Herlihy. She had been strongly influenced by the writings of Monsignor Moses Coady of Novia Scotia, who had formulated a co-operative philosophy based on people asserting control of their monetary and consumer rights. Nora Herlihy’s enthusiasm was tempered by caution. Having studied the weaknesses of the Irish agricultural credit societies, the so-called land banks, she was conscious of the need for a proper legal code to provide adequate controls. In the National Co-op Council, she promoted the concept of credit unions to meet social and economic needs.

The fledgling Irish credit union movement drew strength and inspiration from other sources, especially the Credit Union National Association (CUNA), Wisconsin, USA, the headquarters of the World Council of Credit Unions (WoCCU). There was also an influence from the southern hemisphere through Helen Fowler from the Australian parish credit unions. Many clergy, including Bishops Lucey and Philbin, helped to ignite the spark which inspired the credit union movement. The Credit Union Extension Service evolved further. The Credit Union League of Ireland, later named the Irish League of Credit Unions (ILCU), was founded on 7 February 1960 in the old Jury’s Hotel, Dame Street, Dublin.

During the Lemass era, as Ireland moved forward towards a modern economy and a consumer society, there was growing demand for legislative reform. Following lobbying by community groups, a government Committee on Co-operation (1957-1963) was appointed by Sean Lemass, then Minister for Industry and Commerce and later Taoiseach. The committee was chaired by the Registrar of Friendly Societies, Kevin Mangan, a barrister in the Attorney General’s office. A prominent member was activist Nora Herlihy, nominated by the Irish Countrywomen’s Association, a body with co-operative origins dating back to Sir Horace Plunkett. The Committee issued its report in 1963 and recommended new legislation for credit unions. Law reform was supported by Jack Lynch as Minister for Industry and Commerce.

A watershed—the Credit Union Act 1966

Sean Flanagan TD, Parliamentary Secretary to Dr. Patrick Hillery, Minister for Industry and Commerce, steered the Bill through the parliamentary process with support from all parties. Nora Herlihy was justly proud of pioneering the efforts as she stood beside President de Valera when he signed into law the Credit Union Act 1966. Although the Victorian self-help laws in the Industrial and Provident Societies Act 1893 were retained as the basis, the 1966 Act was a watershed in the history of the Irish credit union movement because it gave statutory recognition to co-op concepts including the mutuality of members in the ownership and organisation of their societies. The Registrar of Friendly Societies, an independent officer under the aegis of the Department of Industry and Commerce (now Enterprise and Employment) was designated as the regulatory authority under the Credit Union Act. Membership of credit unions was based on the concept of a common bond between members in neighbourhoods and employment. A Credit Union Advisory Committee, with Nora Herlihy in the chair, advised the minister and formulated model rules. Jim Ivers and Seamus Mac Eoin were prominent on the committee.

The League and Northern Ireland

Under the League’s aegis, the credit union movement spread to Northern Ireland in the 1960s spearheaded by John Hume, now MP for Foyle, who became the second president of the League. The Derry priest, Fr Anthony Mulvey, ably supported Hume’s efforts. The ILCU, a non-sectarian and non-political organisation, became the umbrella body of the all-Ireland credit union movement. Over 520 Irish credit unions, including approximately 140 in Northern Ireland, affiliated to the ILCU. In recent years, however, following increased interest within the Protestant community, there is a trend for new credit unions in unionist areas of the North to affiliate to a British-based federation.

Conclusion

In July 1994, Mary Robinson, President of Ireland, spoke in Cork to delegates of the World Council of Credit Unions (WoCCU) representing 88 million members in eighty-five countries with savings of $433 billion. An Irishman, Gus Murray, presided over WoCCU. President Robinson paid tribute to the Irish credit union movement which accounts for over 1.5 million members, with £1.4 billion in personal savings and assets among about 560 credit unions most of which are affiliated to the League. Those impressive figures belie negative notions about the lack of success of co-operative credit, conveyed officially in the Ireland of the 1930s to 1950s as conventional wisdom. The Irish credit union movement, based on voluntary self-help community efforts and inspired by idealism, surely deserves a prominent place in the social and economic history of the Irish people.

Anthony P. Quinn is a member of the Society for Co-op Studies in Ireland and associate of the Plunkett Foundation, Oxford.

Further reading:

P. Bolger, The Irish Co-operative Movement—its history and development (Dublin 1977).

A.P. Quinn, Credit Unions in Ireland (Dublin 1994 ).

M. Henry (ed.) with P. Bolger and T. West, ICOS—Fruits of a Century: an illustrated history 1894-1994 (Dublin 1994).

T. West, Horace Plunkett, Co-operation and Politics: an Irish biography, (Buckinghamshire and Washington DC 1986).