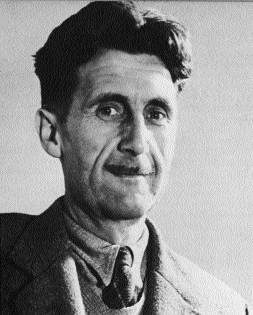

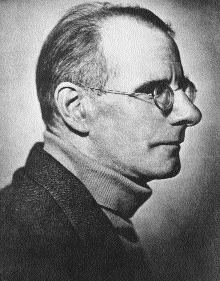

George Orwell & Sean O’Casey

Published in 20th-century / Contemporary History, Features, Issue 3 (Autumn 1998), Volume 6

George Orwell an agent of British Intelligence? Public records released in July 1996 reveal that the British writer in 1949 had supplied a secret propaganda unit in the Foreign Office, the Information Research Department, with a list of about a hundred writers, artists and intellectuals who should not be invited to become covert cheerleaders in the British Government’s campaign against Soviet Communism. At that time he was asked for suggestions of persons who would be useful for this purpose; he offered his list of those who should be excluded. For several years he had been drawing up the list, with contributions from Richard Rees and Arthur Koestler, the noted ex-communist writer, of ‘crypto-Communists, fellow-travellers or inclined that way, and should not be trusted as propagandists’. As early as the end of 1944 Orwell had voiced his great concern about the possibility of disloyalty among English intellectuals and the need to find out who these people were. In the Tribune of 8 December l944 he declared, ‘In my opinion a few pacifists are inwardly pro-Nazi, and extremist left-wing parties inevitably contain Fascist spies. The important thing is to discover which individuals are honest and which are not.’ Among the writers on his annotated list were George Bernard Shaw, J.B. Priestley, Kingsley Martin and C. Day Lewis. Actors were also suspect: Michael Redgrave, Paul Robeson and Orson Welles. Included in the list was Sean O’Casey, the Irish playwright, beside whose name was the annotation ‘Very stupid’. Had he known of Orwell’s activity, O’Casey would not have been surprised; earlier they had had a verbal clash of arms.

Savage review

In October 1945 Orwell had written in The Observer a savage review of Drums Under the Window, the fourth volume of O’Casey’s rambling autobiography. At the beginning of what was little more than an insulting outburst, Orwell set the tone for what followed: ‘W.B. Yeats once said that a dog does not praise its fleas, but this is somewhat contradicted by the special status enjoyed in this country by Irish nationalist writers’.

‘Why is it’, asked Orwell, ‘that the worst extremes of jingoism and racialism have to be tolerated when they come from an Irishman?’ He saw the reason as being ‘England’s bad conscience’: ‘It is difficult to object to Irish nationalism without seeming to condone centuries of English tyranny and exploitation’. Referring to O’Casey’s description of the execution of some Irish political prisoners, Orwell commented: ‘So literary judgement is perverted by political sympathy, and Mr. O’Casey and others like him are able to remain almost immune from criticism.’

According to Orwell, O’Casey’s ‘outstanding characteristic is the romantic nationalism which he manages to combine with Communism’. Moreover, ‘this book contains literally no reference to England which is not hostile or contemptuous’. He also criticised the Irish dramatist for pretentiousness, bombast and imitative writing.

Orwell’s English patriotism

Why this diatribe? Previously Orwell had only shown a peripheral interest in Irish affairs. There is no evidence that his wife, Eileen Maud O’Shaughnessy, whose family had come to England a century earlier, had a sense of Irish identity or an attachment to Catholicism and Orwell never visited Ireland. What brought Ireland and the Irish into his focus was his work as a writer and broadcaster during World War II in which he extolled the virtues of English patriotism. Anything that stood in the way of the English interest in this emergency Orwell looked upon with suspicion and hostility. Christopher Hollis, his friend and fellow-writer, has said that ‘the deepest of all Orwell’s emotions was his overwhelming love of England’, but he ‘did not fully understand that other people might have as deep a love for their national way of life and be prepared with uncompromising loyalty to defend it against all attacks from without as he himself had for the English way.’

Ireland ‘a sham independent country’

In February 1941 Orwell noted in his diary what Sebastian Haffner had to say about the neutrality of the Irish state in the war: ‘The spectacle of our allowing a sham-independent country like Ireland to defy us simply makes all Europe laugh at us’. Orwell foresaw the difficulty of precipitous action: ‘If we took the Irish bases by force without a long course of propaganda beforehand, the effects on public opinion, not only in the USA, but in England, would be disastrous’. In his 1944 essay, ‘The English People’, he declared that the ‘instinctive support for the underdog’ of English people and their bad conscience about their record in Ireland were the ‘real weapons’ used by the Irish in their successful struggle for political independence. These factors ‘prevented the British Government from crushing the rebellion in the only way possible.’ Yet he saw the contest over Ulster as being caused by ‘the expansionist, racist nature of modern Republicanism’.

These two sketches by O’Casey, Dodging Bullets in Dublin during the Revolt and Scene in the Slums after the Looting, from a letter to James Shields (17 July 1916) suggest that he was not the ‘Irish romantic nationalist

Orwell returned to the position of Ireland in the war: It was ‘a sham independent state…hiding behind British protection’. Then there was the position of Catholics in England, ‘the bulk of them very poor Irish labourers’ who were ‘the only really conscious, logical intelligent enemies that democracy has got in England’. This group acted as ‘a silent drag on Labour Party policy, but are not sufficiently under the thumb of their priests to be fascists in sympathy’. Christopher Hollis, his friend and fellow writer, later commented that Orwell ‘disliked the Irish because, he thought, they stood not in opposition to the evils of the times, but in a merely Tibetan isolation from them, and this prejudice in him was confirmed by their neutrality in the war’. Orwell also opposed Scottish nationalism and had a fear of Jewish Zionists whom he privately said ‘everywhere hate us and regard Britain as the enemy, even more than Germany’. As well, he had a marked disregard for the USA. Writing about James Joyce, he remarked that this Irish writer ‘dared…to expose the imbecilities of the inner mind, and in doing so he discovered an America which was under everybody’s nose’. A few months before he wrote his review, he cited O’Casey as an example of an Irish writer who was deluded by the blind assumptions of ‘Celtic nationalism’. The review can be seen as Orwell’s reckoning with the irritating Irish.

O’Casey’s response

O’Casey, who had been living in England since 1926, reacted to the review in characteristic fashion, firing off a spirited letter in response to what he later called Orwell’s ‘agonised yell’ and ‘jingo snarl’. In rejecting Orwell’s claim that his ‘life-work is abusing England’, O’Casey asserted that he was ‘one who had built up the greater part of his educated life’ from reading the great works of English literature, which, he said, showed ‘an admiration for England’s achievements that Orwell himself could hardly excel’. Furthermore, ‘I’ll venture the statement that I know far and away more about England than he knows about my country’.

Having declined to accept the financially secure position of resident Irish dramatist within the London artistic community (and for that matter, any Soviet hand-outs), O’Casey was particularly sensitive to the implied charge that he was living off the English proceeds of his works. He noted that he received ‘near as much from his own country as from England, and much more from America’. As to the ‘blatant nationalism’ that Orwell found in his book, O’Casey argued that by failing to note the final sentence in the work—‘Poor, dear, dead men; poor W.B. Yeats’—Orwell had omitted O’Casey’s ‘sadly ironical’ view of Irish chauvinism. In addition, O’Casey pointed out that the bit of poetry that Orwell cited as an example of this:

Singing of men that in battle array

Ready in heart and ready in hand,

March with banner and bugle and fife

To the death, for their native land.

was not from the pen of an Irish writer but from that of Tennyson!

The Observer did not print O’Casey’s letter, and Orwell did not respond when it was forwarded to him. In Nineteen Eighty-four (1949), Orwell gave the very Irish name of O’Brien to the important character who, at the Ministry of Love, directed the campaign to stifle every aspect of individualism which could challenge the dominance of the Party and State. Orwell provides this description of the character: ‘A large, burly man with a thick neck and a coarse, humorous, brutal face. In spite of his formidable appearance he had a certain charm of manner’. According to Christopher Hollis, Orwell chose an Irish identity for this character, which Hollis found to be ‘amusing’, because Orwell held that once Irish people were outside the domination of their church, they would make a new faith out of a quest for power, while retaining authoritarian habits from Catholic training.

Meanwhile O’Casey believed he had discovered the basis of Orwell’s antipathy towards him. Plowing through old letters in 1947, he came across one from 1935 in which he declined the invitation of a Left Books editor to offer praise of Orwell’s first book, The Clergyman’s Daughter, declaring that he ‘could not for a moment agree with your high opinion of it’. The same year O’Casey wrote a letter, printed in the Daily Worker and the Irish Press in which, among other things, he said that Orwell ‘got very angry because he thought there was too much Irish nationalism in his book’, and cited Orwell’s mistake about the Tennyson poem.

Orwell’s profound pessimism

In his final volume of autobiography, Sunset and Evening Star (1954), published four years after Orwell’s death, O’Casey gave full vent to what he saw as Orwell’s profound pessimism about the human prospect. He said of Orwell, ‘Dying, he wanted the living world to die with him. It seemed to comfort his ailing nature to believe that he was leaving a perishing world, a world that would soon ignobly and terribly die.’

Returning to the charge that resident Irish writers were sponging off the English reading public, O’Casey noted that almost all of his meagre income derived from American and Irish sources and all of it was taxed in England. As to the assertion that he hated the country of his residence, he cited the extensive record of his family’s service in the British Army, including that of his two sons. Orwell’s attitude, according to O’Casey, came down to this: ‘Get outa me country’. Although Orwell was being held up as a model of the principled rebel, O’Casey saw him as ‘a yielding blob that buried itself away from the problems of living that all life has to face and overcome’.

Just to rub it in, and taking poetic license, O’Casey provides a tale in which an Irish friend and himself are driven by freezing rain into an English pub, the Rose and Crown, and observe the very same George Orwell and a seedy English gossip columnist drinking iced beer. Sean and his friend are shortly joined by none other than Cathleen na Houlihan, who is in a definitely post-Holyhead frame of mind. Objecting to the ensuing Irish hooley, Orwell and companion vaporise in indignation.

‘A bitter raging disappointed man’

O’Casey also went after Orwell in several letters written in 1955. Perhaps partially goaded by a writer in the Irish Times who attacked him for ‘venting of venom on people like George Orwell, who was worth twenty of him any day of the week’, O’Casey told one correspondent, ‘Orwell, to my thinking, was just a bitter raging disappointed man, riddled with disease, and one who, instead of fighting his ailment, wasted his life railing at those healthier than himself’. Responding to the assertion that he only attacked Orwell after the latter’s death, O’Casey wrote to someone else, ‘I gave the punch to Orwell years before he died…. Orwell’s review was an attack on Ireland as well as on me, and I defended myself and Ireland from him’. Defensive warfare indeed!

So concluded the brief but abrasive intersection of two of the great writers and controversialists of the era—the Irish champion of his country’s freedom and idealistic communism and the eccentric scourge of elements in British socialism and of Soviet totalitarianism, a vignette in the clash of nationalism and chauvinism, of revolutionary socialism and English gradualism.

Arthur Mitchell is professor of history at the University of South Carolina

Further reading:

C. Hollis, A Study of George Orwell: the man and his works (London 1956).

D. Krause (ed.), Letters of Sean O’Casey, 1943-1954, vol. 2, 1955-1958, vol. 3 (Washington DC 1976, 1977).

S. O’Casey, Sunset and Evening Star (New York 1954).

S. Orwell and I. Angus (eds.) Collected Essays, Journalism and Letters of George Orwell, vol. 2 (New York 1968).