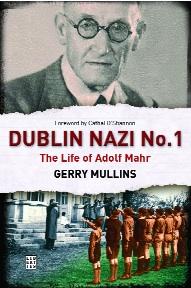

Dublin Nazi No. 1: the life of Adolf Mahr

Published in 20th-century / Contemporary History, Issue 5 (Sep/Oct 2007), Reviews, The Emergency, Volume 15

Dublin Nazi No. 1: the life of Adolf Mahr

Gerry Mullins

(Liberties Press, €25 hb, €16.99 pb)

ISBN 9781905483198

In 1927 the Austrian Adolph Mahr became Keeper of Irish Antiquities at the National Museum in Kildare Street, Dublin, one of a diverse group of European professionals recruited by the fledgling Irish Free State. Made director in 1933, he played a crucial role in introducing a more scientific methodology to Irish archaeology, helped to implement the Lithberg report and to draft the National Monuments Act, and is considered by many to be the ‘father of Irish archaeology’. Gerry Mullins’s biography deals with Mahr’s other, more embarrassing, role in Dublin society. Between 1934 and early 1939 he was head of the Nazi Party in Ireland, which he helped to establish.

Mahr’s duties included keeping tabs on German’s in Ireland, sending regular reports on Irish developments back to Berlin and asserting the dominance of the Nazi Party over other agencies of the German government abroad—in this case the Foreign Office. Irish newspaper editors and politicians seem to have shown a baffling lack of awareness of the potential dangers of having an arm of the Nazi Party in direct control of the German colony in Ireland. In addition to having their own Hitler Youth wing, members of the Nazi Party in Ireland held important positions in the Irish economy, including in the ESB and the Turf Board.

By 1937 Mahr had been at least partially responsible for the removal of two German ministers to Ireland and had attracted the attentions of Irish military intelligence. His position as an Irish civil servant and the agent of a foreign power was anomalous at a time when civil servants were forbidden to be members even of domestic political parties. In early 1939 Mahr left to attend a conference, and initially it was assumed that the war would be brief and that he would shortly resume his duties. Events turned out differently. Mahr ended up as the head of Irland Redaktion, coordinating propaganda broadcasts to neutral Ireland. After the war Mahr was interned by the Allies, and later did his best to return to his job in the National Museum (from which he had technically been taking a leave of absence). The Irish government were understandably reluctant to admit him. Mahr, like other Nazi officials, had been arrested, mistreated, and released without being subjected to anything particularly out of the ordinary. With the Reich in ruins, Dublin’s Nazi No. 1 became merely another ex-official to be moved through the de-Nazification procedure. He died in 1951 amidst the wreckage that his party had brought to Germany.

Mahr’s departure to Germany in 1939 was not directly connected with his work for the Nazis. While he was under increased surveillance as war approached, he had already abandoned his position as head of the Auslandorganisation. He does not appear to have been responsible for Nazi espionage in the Free State prior to the war, nor was he closely involved with the preparations for Fall Grun, the planned invasion of Ireland. It is also unclear whether he would really have become Nazi Gauleiter in an Irish satellite state after a German victory (although he would have been a prime candidate). Mahr seems to have been principally dangerous to his fellow Germans—a list despatched to Berlin details his compatriots and includes the term Jude in brackets after the names of known Jews. Mahr may not have been aware that he had, in effect, signed a series of post-dated death warrants. It was, however, public knowledge that he was exposing those Jews he helped to identify to the theft of their property and their expulsion from public life.

Mullins’s description of Mahr’s work with Irland Redaktion is of great interest. The decision to shift broadcasts away from the Irish-language and to focus propaganda efforts on an anti-imperial, anti-partition and pro-neutrality campaign shows a shrewd grasp of Irish affairs. Similarly, his efforts to use Irish America as a tool to promote isolationism in the US and his decision not to emphasise anti-Semitic propaganda themes (of little value in Ireland, which had a comparatively small Jewish population) demonstrate Mahr’s value to Goebbels’s organisation. While the remaining Jews vanished and the Allied bombing campaign began to bite, Mahr’s career in radio propaganda made rapid progress. By 1944 he had been appointed to head Ru IX and Ru II, which dealt with broadcasts to Britain, Ireland and the British Empire. Much of Mahr’s Irish experience ceased to be significant to the war effort as German agents were systematically arrested in Ireland and it became steadily more apparent that Ireland would not be invaded.

Mullins seems ambivalent as to his subject’s position on the Jewish question. Mahr continued his correspondence with Jewish colleagues, and on at least one occasion tried to help an acquaintance find refuge in the United States. Mullins stresses the German nationalism at the heart of Mahr’s Nazism, his anguish at Germany’s defeat in the First World War, his pride at the restoration of German greatness, and his comparison of the German and Irish positions on national reunification. This doubtless explains much of the emotional charge behind Mahr’s allegiance to Nazi Germany, but several of the letters that Mullins cites suggest a different view. Nazism was not merely an extreme form of German nationalism but a Weltanschaung (world-view) complete unto itself, and there is ample evidence that Mahr shared in it. Nazi ideology stressed the significance of the Aryans (culture creators) and their eternal enemies, the Jews (culture destroyers). In place of what they perceived to be an artificial division of society into classes and the world into sovereign states, the Nazis planned to reconstruct Germany as a racial community based on the Volk and to redefine international affairs on racial grounds. That this was not merely propaganda is apparent from the continuation of the Holocaust long after it was clear that the war was lost.

In 1932 Mahr wrote a letter to Albert Bender, an American Jewish philanthropist of Irish descent:

‘We anthropologists . . . know that the present national and racial boundaries are a thing of very late origin and that the boundaries which separated mankind in the Stone Age are probably more important than the make-shifts of our present politicians. There is a growing sense amongst anthropologists . . . to lose interest in what is today miscalled “politics”.’

Shortly afterwards, Adolf Hitler would begin to remake the world based on his interpretation of the racial boundaries ‘which separated mankind in the Stone Age’. Anthropologists and archaeologists would help him. Later in the Bender correspondence Mahr would defend the Third Reich from allegations of ‘fourteenth-century barbarism’ and allude to Germany’s quarrel with ‘international Jewry’ while making reference to the Balfour declaration and other standbys of Nazi ideology.

Mullins expresses his confusion as to Mahr’s motivations at a joint SS, Propaganda Office and Foreign Office conference in 1944 when he called for the drawing up of lists of ‘pro-Jewish’ Freemasons, journalists, writers and economists. While Mahr may not have understood the full significance of inscribing Jude or ‘Israel’ on earlier lists, there can have been no conceivable doubt as to the use to which they would be put in 1944. After his own tour of the Baltic States and his son’s experience with the Wehrmacht in the East, Mahr knew that he was drawing up death-lists. Mullins comments that Mahr ‘comes across as an ardent anti-Semite in calling for anti-Jewish propaganda in foreign radio services, yet in the service where he had control, there was little such material’. The contradiction here is only apparent. Mullins has demonstrated that Mahr subscribed to anti-Semitic publications and was a believer in ‘international Jewry’ as a coherent entity opposed to the German nation. His apparent lack of personal animus against individual Jews was not terribly unusual among Nazi Party officials, who often managed to disassociate the individuals they knew from the racial enemies they exterminated. In this context, the relative lack of anti-Semitic content on Irland Redaktion is explicable as a tactical move.

Mullins seems to believe that ‘Mahr was . . . like hundreds of millions of others, a victim of the fact that he lived in a time of war’. But this is not the case. Nothing compelled Mahr to join the Nazi movement: unlike those Germans who were still in Germany, he was not dependent on the Party for work or status in society. Mahr appeared to be an anti-Semite at so many periods throughout his life because that’s what he was. He was a believer in National Socialism, did his duty as a ‘national comrade’, assisted the Party in its struggle against the perceived Jewish menace, and never appears to have questioned the evidence on which the Party’s ideology was based. In the final analysis, Mahr failed as a scholar, as a scientist and as a man.

Michael Gibbons is a member of the Institute of Irish Archaeologists.