Children of the Revolution

Published in 20th-century / Contemporary History, Features, Issue 3 May/June2013, Revolutionary Period 1912-23, Volume 21 Shortly before noon on Easter Monday 1916, Catherine Foster left her home in 18 Manor Place in Stoneybatter, pushing her two-year-old child, John Francis, in his pram towards the city centre. As she reached the junction of North King Street, she encountered a barricade being hastily built by the Volunteers under the leadership of Piaras Biaslaí. Just as she passed, a gun battle broke out as Lancers travelling along the quays were fired upon. One was shot and another ‘galloped up Church Street firing wildly and was shot down after he had killed a child’. John Francis Foster was aged two years and ten months when he was shot in his pram. His mother rushed around the corner to the Richmond Hospital but it was too late, he having been ‘shot through the head at level of ears’. He was the first of 30 children aged sixteen and under who were killed during the Easter Rising.

Shortly before noon on Easter Monday 1916, Catherine Foster left her home in 18 Manor Place in Stoneybatter, pushing her two-year-old child, John Francis, in his pram towards the city centre. As she reached the junction of North King Street, she encountered a barricade being hastily built by the Volunteers under the leadership of Piaras Biaslaí. Just as she passed, a gun battle broke out as Lancers travelling along the quays were fired upon. One was shot and another ‘galloped up Church Street firing wildly and was shot down after he had killed a child’. John Francis Foster was aged two years and ten months when he was shot in his pram. His mother rushed around the corner to the Richmond Hospital but it was too late, he having been ‘shot through the head at level of ears’. He was the first of 30 children aged sixteen and under who were killed during the Easter Rising.

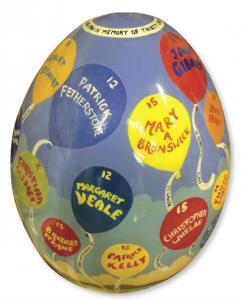

It was almost by accident that I decided to find out the number of children killed during the Rising. The children’s charity Jack and Jill asked 100 ‘well-known’ people to paint a four-foot egg for public display in the period leading up to Easter 2013. Being an amateur artist, I knew I would need a decent story to back up any painting I might conjure. Conflating the charity and the occasion, the idea of listing the children killed in the Easter Rising suggested itself. And given that the most memorable line for many from the Proclamation is ‘cherishing all the children of the nation equally’, it is appropriate that we should list the children who died in the six days after it was pasted to the front of the GPO.

I then discovered that historian Dr Ann Matthews had raised the issue at the Parnell Summer School in 2011, calling for the ‘28 children who were killed in the Rising’ to be commemorated. In Renegades Dr Matthews had begun to compile a list, though some Christian names and many addresses were absent. Using this list, death certificates, newspaper reports, the 1911 census and the Glasnevin Trust records, I set about constructing as comprehensive a list as possible. My aim was to paint the egg by naming these children, using balloons against a landscape for each child, with their age and address also inscribed.

Of the 450 who perished during the six days of fighting, 224 were adult civilians, 116 British soldiers, 64 rebels, 30 children and sixteen policemen. Six of the children killed were aged ten and under; two were only two years old. Most of the children killed were aged between eleven and sixteen. Three of the 30 were members of Na Fianna.

Above: Members of Na Fianna Éireann engaging in first-aid exercise in Dublin’s Merrion Square c. 1917. Three of the 30 children killed in Easter 1916 were members; one was a member of the Irish Citizen Army. (NLI)

The attached list shows that the majority were shot close to the city centre—many lived in tenement housing. In terms of adding to our understanding of the Easter Rising, the list reminds us of the intense nature of the conflict in a relatively small area. From death certificates it is clear that most were killed accidentally by gunfire. Given that most of the group were teenagers, can we presume that they were the ones being sent out to forage for food as the city was in turmoil?

The 30 children killed

1 Bridget Allen (16), 27 Arran Quay. Bullet wound.

2 Christopher Andrews (14), 8 Stephens Place, Mount Street. Bullet wound.

3 Mary A. Brunswick (15), 57 Lower Wellington Quay. Laceration of the brain.

4 Christina Caffrey (2), 27 Corporation Buildings. Bullet wound, outside home.

5 Christopher Cathcart (10), 28 Charlemont Street. Bullet wound.

6 Moses Doyle (9), Whitefriar Street. Shot at his home.

7 Charles Darcy (15), 4 Murphy’s Cottages, Gloucester Street. Member of the Irish Citizen Army.

8 Patrick Fetherstone (12), 1 Long Lane, Dorset Street. Bullet wound.

9 John Francis Foster (2), 18 Manor Place, Stoneybatter. Shot in his pram.

10 James Fox (16), 74 Thomas Street. Member of Na Fianna.

11 John Gibney (5), 16 Henrietta Place. Died as a result of ‘cannonading’.

12 John Healy (14), 188 Phibsborough Road. Messenger boy for Na Fianna.

13 Christopher Hickey (16), 168 North King Street. Shot with his father.

14 James Jessop (12), 3 Upper Gloucester Street.

15 Charles Kavanagh (15), 4 North King Street. Bullet wound.

16 Mary Kelly (12), 128 Townsend Street. Bullet wound.

17 Patrick Kelly (12), 24 Buckingham Buildings. Gunshot wound to the neck.

18 Bridget McKane, 10 Henry Place. Killed during the rebel retreat from the GPO.

19 John H. McNamara (12), 45 York Street. Died at Mercers Hospital.

20 William Mullen (9), 8 Moore Place. Shot in the thorax during the rebel retreat from the GPO.

21 William O’Neill (16), 93 Church Street.

22 Mary Redmond (16), 4 Mary’s Abbey.

23 Patrick Ryan (13), 2 Sitric Place.

24 George Percy Sainsbury (9), 54 South Circular Road. Killed at Haroldville Terrace.

25 Walter Scott (8), 16 Irvine Crescent (north dock).

26 Bridget Stewart (11), 3 Pembroke Cottages. Bullet wound.

27 Margaret M. Veale (13), 103 Haddington Road. Shot at her window.

28 Philip Walsh (11), 10 Hackett’s Court. Gunshot to the abdomen.

29 Eleanor Warbrook (15), 7 Fumbally Lane. Shot in the head.

30 Christopher Whelan (15), 30 North Great George’s Street.

Gerald Playfair: How a 1916 myth lives on

When I compiled this list little did I know that the reaction would help unravel one of the great misunderstandings of 1916. A number of people contacted me to tell me that I had left out one child—‘Gerald Playfair, the 14-year-old son of a British soldier killed in cold blood by the rebels in the Phoenix Park’. Indeed many history books about the Rising published here in the last two decades have referred to the killing of the ‘14-year-old’ Gerald Playfair (although some refer to him as 17).

His name and age also appear in newspaper columns, blogs, tweets and postings about the Rising—often being cited as evidence of the ‘blood lust’ of the rebels. True, a ‘G. Playfair’ was killed in the Easter Rising but when I retrieved the death certificate from the General Register Office it revealed a different story. George Alexander Playfair, a 23-year-old clerk in Inland Revenue, died from ‘bullet wounds to the abdomen’ nine hours after he was shot in 1 Park Place, beside the Islandbridge gate to the Phoenix Park. This was Gerald’s older brother. The family lived in the Magazine Fort—a British Army munitions depot in the Phoenix Park, a key target on Easter Monday morning for the insurgents—where their father, George, was commandant. Newspapers at the time reported that the ‘eldest son of Mrs Georgina Playfair’ was killed by insurgents when he tried to raise the alarm. They assumed that the eldest child was Gerald. Indeed the 1911 census records that there were five children and Gerald was the eldest boy on the census form. But it also revealed in small print that there were six children still living! George, the eldest child, was absent as he was studying in England at the time.

Another reason for the confusion was that the insurgent who shot George Playfair said he looked ‘about 17’. His death is recorded in the Irish War Memorial ‘ordinance department’, indicating that he may have been in the British Army reserve. Gerald Playfair, the 14-year-old boy who many historians and commentators have recorded as the ‘first fatality’ of the Easter Rising in 1916, in fact was not shot or wounded but went to live in Canada where he was married in Toronto in 1923.

Joe Duffy is a broadcaster and journalist.

Further reading

A. Matthews, Renegades: Irish republican women 1900–1922 (Cork, 2010).

Rebellion Handbook [Irish Times] (Dublin, 1917).

The author would like to thank Dr Ann Matthews, Shane Mac Thomáis (Glasnevin Trust) and Hugh Comerford (Dublin City Libraries).