1969: the North erupts

Published in 20th-century / Contemporary History, Features, Issue 4 (Jul/Aug 2009), Troubles in Northern Ireland, Volume 17

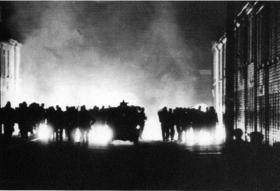

A line of RUC and B-Specials moves along Hooker Street in Catholic Ardoyne on the night of 14/15 August 1969, backlit by the fires of loyalist arsonists (note the absence of street lights, already shot out by police). Two Catholics were killed by the RUC and B-Specials in the Ardoyne area, and one Protestant on the nearby Crumlin Road by nationalist gunmen. The Scarman Tribunal later found that on several occasions, as the RUC and B-Specials pushed Catholics back, loyalist mobs followed in their wake, burning houses as they went. (Belfast Telegraph)

In introducing this special issue Brian Hanley touches on some of the complexities and contradictions of that fateful year.

The events in the North in 1969 transformed Ireland; it could be argued that the violence of that August continues to shape this country to the present day. Yet in comparison to ’68, commemorated last year by conferences, books and TV documentaries (and History Ireland), 1969 is curiously underrepresented. We hope that this issue of History Ireland will encourage a closer look at the politics and events of that year (see Gordon Gillespie’s narrative, pp 16–19). Today very different views on what occurred during 1969 are held by people living on either side of the ‘peace lines’ in Belfast, structures first established in the wake of the August events (see Jonathon Byrne, p. 43). Both communities hold their conflicting ‘memories’ dear, and rival political organisations have invested much in their own readings of the outbreak of the Troubles. In the South, not only does the usual ignorance about Northern Ireland apply but there are also political reputations tied up in the response of the Irish state in 1969.

Even a cursory look at some of the eighteen fatalities in Northern Ireland that year reveals complexities. The first British soldier to die in the conflict, Hugh McCabe (home on leave), was killed by RUC gunfire. The first RUC officer to be killed, Victor Arbuckle, was shot dead by loyalists, probably the UVF; the first two civilians killed by the British Army, Herbert Hawe and George Dickie, were Protestants, shot on the Shankill Road in October. The IRA (non-existent according to some accounts) caused the first fatality of the August violence in Belfast, loyalist Herbert Roy, more than likely by a Thomson submachine-gun (see Lar Joye, p. 39). The youngest person to die, nine-year-old Patrick Rooney, was killed by the RUC, while the next victim closest in age to him was fifteen-year-old Gerald McAuley, the first republican fatality of the Troubles. At the time the death toll seemed almost unimaginably terrible. This is because in the context of Northern Ireland’s short history it was; there had not been inter-communal violence on this scale since 1935, and prior to that since 1920–2. From the vantage point of 40 years and over 3,500 deaths later it is easy to imagine that such violence was an everyday occurrence; but despite flare-ups in Belfast during 1964 and 1966, it was not. Indeed, some commentators had been optimistically predicting improving community relations throughout the 1960s. For most people in Ireland, what occurred in 1969 was new and unexpected. It has often been viewed through the perspective of what happened afterwards. Given the scale of what took place after 1970, much of what happened until August 1969 can seem minor. But it is important to stress that it did not seem like that at the time. In April 1969 the Irish News described rioting in Derry and Belfast as the ‘most devastating wave of violence and civil strife’ since the 1930s. Then in early August fierce fighting between loyalists and the RUC on the Shankill was regarded as the worst violence the city had seen. Just over a week later the Battle of the Bogside began, followed by the explosion of August 13–15 in Belfast.

The aftermath—an old woman surveys the wreckage on the Falls Road. (Belfast News Letter)

In retrospect we can trace radicalisation since January, when the loyalist attack on the People’s Democracy march at Burntollet was followed by rioting in Derry, and a week later by more trouble in Newry; there was rioting in both Derry and Belfast in April, and the first reports of people being forced from their homes in the city also came that month. A particular flashpoint was Ardoyne, where a local priest, Fr Marcellus Gillespie, attested that during the early summer ‘Catholics were as much to blame as Protestants’ for the clashes. That may surprise some today, but Protestants would also be the victims of sectarian violence in 1969, among them William King, who died after being beaten up in Derry during September. Hence many loyalists still believe that it was Catholic aggression that sparked off the trouble in Belfast, while some also celebrate (on YouTube and elsewhere) the burning of Catholic homes in ‘response’. But as Ian S. Wood shows (pp 20–3), loyalists had killed as early as 1966 and the UVF were planting bombs aimed at bringing down Terence O’Neill in the spring of 1969. The Shankill Defence Association, led by John McKeague (see Patrick Maume, p. 66), was active in spearheading attacks on Catholics in early August. Catholics comprised the majority of 1969’s victims, both those killed and those forced from their homes. At least eight of the nine Catholic dead during 1969 were killed by the RUC or the B-Specials. In Belfast especially the violence brought back powerful memories of the pogroms of 1920–2. Coming on top of the resistance of many unionists to the demands of the Civil Rights movement, it is unsurprising that nationalists remember themselves as defenceless victims of unprovoked attacks.

But that is only partly the reality. Two Protestants were also killed in the fighting in Belfast, which erupted after republicans attacked police barracks and personnel to draw their forces away from Derry on 13 August (see Hanley, pp 24–7). While no doubt poorly armed, the idea that the IRA had little interest in armed politics simply does not stand up to examination, nor indeed does the belief that nationalists automatically accused it of having let them down in the aftermath of the August events. The IRA was growing during 1969 and increasingly active, North and South. It was thrown into crisis by the August events, but less by the reaction of nationalists to its ‘performance’ than by the disenchantment of former members to what they perceived as a failure caused by a concentration on ‘politics’. The memory of these events was further complicated by the bitterness surrounding the republican split in 1969–70 and the diverging paths of those concerned. Those who became the Official IRA and later the Workers’ Party played down and then rewrote entirely their role in the violence, creating a new narrative of a completely peaceful civil rights strategy. Their rivals in the Provisionals, meanwhile, would invest a great deal in their claim to have emerged organically from the demand by disillusioned nationalists for defence.

The story would be further complicated by the intervention of the Irish government, taken by surprise and at sea in the early stages of the crisis, flirting with military intervention and shaken by a wave of nationalist feeling in the South, all outlined in articles by Dermot Keogh (pp 28–31), Edward Longwill (pp 32–5) and Niamh Puirséil (pp 36–8). In this context money and arms went north, some of it supplied by politicians, and both rival republican factions benefited. What the crisis revealed, however, was how little attention had really been paid to Northern Ireland by Dublin. The same has been said of London, but this does not seem to have been entirely the case, as Paul Bew shows (pp 46–9). Yet the British government were also ill-prepared for the violence of August, and their deployment of the British Army was a stopgap, not a considered attempt at a solution. The shock waves reached the United States too, with interest in Ireland reaching a level not seen since the 1920s (see Tara Keenan-Thompson, pp 44–5). Despite what some have wishfully imagined, the substantial reforms introduced that winter, which included the disbandment of the B-Specials and the disarming of the RUC, came as a response to the violence of August, not because of the strength of the Civil Rights movement. That movement was already fracturing by the summer of 1969, riven by disputes about strategy and ideology. Whatever hopes there may have been in O’Neill’s reforms were being tested by the resistance of much of unionism to the idea of any change at all. Ian Paisley and others were describing any compromise as treachery and increasingly winning mass support. But despite the violence of that year, many areas of the North saw little trouble during 1969, and even much of Belfast was uneasily quiet during August, as Liam Kelly explains (pp 40–2). If the events of that year were unexpected, it is also true that no one foresaw that they would be the beginning of a conflict that would last 30 years, aspects of which we also examine in our regular Film Eye (pp 50–1), TV Eye (pp 52–3), Bookworm (pp 54–5) and book reviews (pp 56–65). HI

Brian Hanley lectures in history at Queen’s University, Belfast.