1914–18 and the War on peace

Published in Features, Issue 4 (July/August 2014), Volume 22

Conscientious objectors take a break from breaking stones in Dyce prison camp, outside Aberdeen, in October 1916.

These networks of intellectuals and activists included well-known Irish women and men. Acknowl-edging the history of these Europe-wide coteries provides a necessary frame for understanding both Ireland’s revolutionary turn and more specific contexts such as the death of a pacifist like Francis Sheehy Skeffington or the split loyalty of a combatant such as Tom Kettle.

‘Conchies’ targeted

Once war had been declared, those who had tried to awaken public consciousness with regard to the impending conflagration regrouped. As the hostilities dragged on, the mechanisms of state intervened and were deployed to close down opposition. Pacifists and conscientious objectors, or ‘conchies’, were targeted by state security agencies. Meetings were infiltrated and broken up, and legislation was passed to arrest and to prosecute peaceniks, preventing their ideas from circulating.

Many revolutionary leaders who had spoken out against the inevitability of war would later on conspire to bring an end to the conflict. Several ringleaders involved in the Easter Rising of 1916, the October Revolution of 1917 and the Spartacist uprising in 1919 had been earlier advocates of peace. But not all pacifists were revolutionaries. The antecedents of Europe’s anti-war movement might be traced back to traditions of non-conformist religion. Both Quakers and intellectual adherents of the Positivist Church of Humanity developed acts of peace and altruism. Feminism, too, developed a strong pacifist dimension. Earlier wars had also fostered anti-war sensibilities. Britain’s confrontation with the Boer republics from 1899 to 1902 initiated the Stop the War Committee founded by investigative journalist W.T. Stead. This was supported by the future prime minister David Lloyd George and the Scottish labour leader Keir Hardie. Various prominent Irish nationalists opposed the war in South Africa. They included the historian Alice Stopford Green and Irish anarchist Nannie Dryhurst.

Following the resounding Liberal victory at the polls in 1906, a group of Liberal MPs worked hard to promote a policy of peace. But the swerve of most Liberal politicians, and, indeed, the Irish Parliamentary Party, was in support of Britain’s empire. The politician and Irish Home Rule architect John Morley was one of the more prominent statesmen who would resign from the cabinet in August 1914 owing to his principled objection to the declaration of war. But such sacrifices brought few rewards, either then or at the hand of history.

Left-wing opposition

![Keir Hardy addressing an anti-war demonstration in London’s Trafalgar Square in 1914. He had earlier supported the Stop the [Boer] War Committee in 1899–1902.](https://www.historyireland.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/07/Keir-Hardie-in-Trafa1DFC82-300x199.png)

Keir Hardy addressing an anti-war demonstration in London’s Trafalgar Square in 1914. He had earlier supported the Stop the [Boer] War Committee in 1899–1902.

The war changed everything. Some dissenting voices fell back into line; both the loyalties of suffragettes and Irish nationalists were split. In Germany opponents to the war joined the New Fatherland League, founded by German physiologist Georg Friedrich Nicolai, and signed the Aufruf an die Europäer (Manifesto to the Europeans). The most prominent signatory was the theoretical physicist Albert Einstein. The following year Nicolai published The bio-logy of war, an indictment of warfare; for this he was imprisoned and relieved of his academic post. In France, Romain Rolland wrote an anti-war blast, Au-dessus de la mêlée (1915), translated as Above the battle (Chicago, 1916). That same year he received the Nobel Prize for Literature.

E.D. Morel and the Union of Democratic Control

Karl Liebknecht, tried for treason in October 1907 for his book Militarism and anti-militarism, addressed a rally of around 10,000 Parisians on 13 July 1914.

In 1912 Morel published Morocco in diplomacy. He dedicated the book ‘to those who believe the establishment of friendlier relations between Britain and Germany to be essential to the prosperity and welfare of the British and German people’. He set out to show how the British public had been misled by a deliberate process of deception and misrepresentation:

‘. . . the British and French peoples alike have been led to the verge of war with Germany, not because of alleged deep-rooted antagonisms of conflicts due to “elemental forces”, but through the intrigues, the lack of straightforward dealing, and the absence of foresight on the part of a diplomacy working in the dark and concealing its manoeuvres from the national gaze’.

Once war was declared, Morel rallied a network of collaborators and allies in both Europe and America. At its foundation the UDC was not a pacifist organisation in the obvious sense. It opposed the war as undemocratic, however, and aimed to develop a credible opposition in advance of a settlement. This opposition would then be positioned to intervene in public debates, thereby influencing events and promoting an abiding and democratic peace. There were further demands for a more transparent foreign policy and for controls on the international arms industry.

In the first months of the war the UDC published a series of pamphlets by recognised public intellectuals; these criticised the official version of why the war had started and promoted a dialogue of peace. Pamphleteers included the Cambridge philosopher Bertrand Russell, the economist and staunch critic of imperialism J.A. Hobson and the journalist H.N. Brailsford. UDC branches were established across England, Wales and Scotland, and in Ireland in Belfast, Cork and Dublin.

Indeed, beyond specific national reactions to the war, there were responses from different international groups that transcended national boundaries. The Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom was founded after a congress held in The Hague in 1915 organised by many leading European feminists, including Aletta Jacobs and Catherine Marshall.

Zimmerwald conference

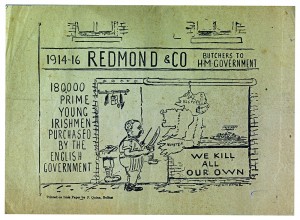

‘We kill all our own’—an anti-war, anti-John Redmond poster. (NLI).

Anti-war agitation spread from Europe to the US. In 1915 one of the most popular songs of the year was ‘I didn’t raise my boy to be a soldier’. The anarchists Emma Goldman and Alexander Berkman set up the No-Conscription League and published a manifesto arguing that conscription breached the ethical and political choice protected by the American constitution.

Censorship and propaganda

But the international efforts by anti-war activists to organise were severely compromised by greater controls of international communication and the hidden hand of censorship and official propaganda. Although the opponents of war were relatively few and their voice swamped by the bombardment of state propaganda, anti-war movements and pacifists were targeted by state security services from very early on. Freedom of speech was heavily suppressed. Meetings were infiltrated and broken up. In the House of Commons, Sir Edward Carson was particularly outspoken in the drive against pacifists.

On 19 August 1915 British police raided the offices of the Independent Labour Party (ILP) and confiscated thousands of pamphlets. By the spring of 1916 many of the leaders had been imprisoned or sentenced to menial labour, including the founder of the No-Conscription League, Archibald Fenner Brockway, and future home secretary Herbert Morrison. At his trial, when asked whether he belonged to any religious denomination, Morrison commented defiantly: ‘I belong to the ILP and Socialism is my religion’.

The pacifist threat was taken seriously. To tackle pacifist propaganda and the efforts to exploit discontent among the British working classes, the National War Aims Committee was set up in the summer of 1917. The head of Special Branch at Scotland Yard, Basil Thomson, was ordered by the permanent under-secretary at the home office, Sir Edward Troup, to produce daily reports on various pacifist organisations.

By the end of 1917, pacifist meetings had been largely closed down and leaders of the movement harassed and imprisoned. The ideas promoted by the pacifists were now targeted. An amendment was made to the Defence of the Realm Act, Regulation 27c, which sought to close down all criticism of government policy. Henceforth, all unofficial leaflets about the war and the future peace had to be passed by the Press Bureau. Bertrand Russell responded with a leaflet titled The new dictatorship of opinion. Lloyd George’s comment, mentioned in the diaries of C.P. Scott, that ‘If people really knew, the war would be stopped tomorrow’ might have applied as much to the home front as it did to the continuing slaughter on the Western Front.

When the peace came, the key demand of the UDC for an equitable distribution of responsibility for the war was ignored. Article 231 of the Treaty of Versailles, known as the ‘war guilt clause’, required Germany and her allies to accept responsibility for all loss and damage. Upstream negotiations in Paris would produce immense turbulence downstream.

Legacy

The organisation of anti-war protests during the First World War would leave a mark across the century. The Union of Democratic Control endured as a think-tank for both the British Labour Party and for anti-colonial agitation. Many of its most outspoken supporters went on to hold senior cabinet positions in the 1920s and 1930s. Bertrand Russell served out his prison sentence at the end of the war . . . and returned to prison in the 1960s, aged 89, for inciting the public to commit a breach of the peace during the anti-nuclear arms protests.

Some historians, such as Jay Winter, have recently argued that the discourse on human rights that came to dominate international re-lations in the late twentieth century owes much to the pacifism of the First World War. The New Fatherland League was renamed the German League for Human Rights. In Britain in 2014, the ‘No Glory in War 1914–18’ campaign is orchestrating a movement to denounce the triumphalism and celebration surrounding many of the centenary commemorations. ‘No Glory’ is endorsed by various public figures, among them the director Ken Loach, actors Vanessa Redgrave and Jude Law, the late Tony Benn, the sculptor Anthony Gormley and the poet laureate Carol Ann Duffy.

Difficult as it may be today to take an unpopular stance against war, it was a much greater act of independent thinking and principled determination to have done so a century ago. The courage of those who placed conscience before country, who saw through the jingoism of the recruitment posters and who defended the common cause of humanity against the tidal wave of hate should not be underestimated. Protests took many forms, from personal stands to organised strikes, mutinies, songs, art and writing. The war resulted in years of untrammelled mass slaughter, but there was an impressive network of individuals and associations who tried to change the tragic course of events that unfolded. As we continue into this decade of centenaries, their stand should be recognised and their example lauded.

Angus Mitchell is the author of 16 Lives: Roger Casement (O’Brien Press, 2014).

Read More: E.D. Morel imprisoned

Unlikely relationships

Further reading

A. Hochschild, To end all wars: how the First World War divided Britain (London, 2011).

E.D. Morel, Truth and the war (London, 1915).

B. Russell, Justice in war-time (Manchester, 1915).