Theatre Eye: Bleeding poets

Published in 18th–19th - Century History, Issue 3 (May/Jun 2008), Reviews, The Famine, Volume 16

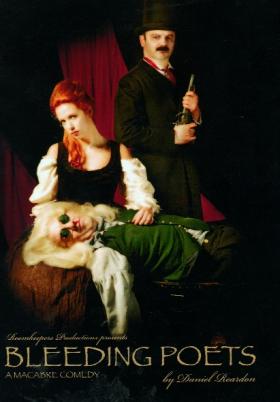

James Clarence Mangan, in blonde wig and green-tinted glasses (Mark O’Regan), being attended to by barmaid Mary Malone (Lisa Lambe), while Edgar Alan Poe (Michael James Ford) looks on. (Roomkeeper Productions)

Bleeding poets

Daniel Reardon

New Theatre, Dublin, Feb.–March 2008

by Eamon O’Flaherty

An imaginary encounter between three poets in a public house in Dublin at the height of the Great Famine forms the basis of this comedy of ideas from Daniel Reardon. The New Theatre is an intimate space, and this suits the claustrophobic atmosphere of Reardon’s play, in which three creative personalities jostle for space in the small bar of the Bleeding Horse Tavern, only held in check by the choleric barmaid Mary, or Molly Malone, as Poe insists on calling her.

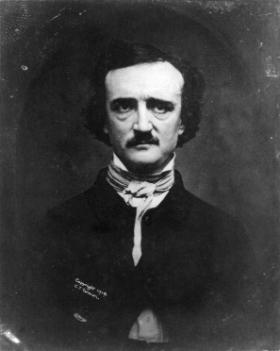

The idea of confronting Edgar Allen Poe and James Clarence Mangan holds out many obvious dramatic possibilities. As tortured souls who explored the darker sides of romanticism and addiction, Poe and Mangan, who both died relatively young and in broken health in 1849, might well have sparked off each other in an imaginary meeting, but the decision to include a third poet—the less well-known Francis Sylvester Mahony—achieves a dramatic and comic tension that is one of the key factors in the success of the play. Mahony, better known by his pseudonym Father Prout, is now a fairly obscure figure in Irish literary history, although he is still remembered as the author of ‘The Bells of Shandon’. Wonderfully played by Arthur Riordan with a plummy Cork accent, Prout’s dramatic entrance into the run-down pub is made more mysterious by his clerical three-cornered hat and black cloak. His mild flirtations with the barmaid suggest ambiguities in his character that occasionally lurk beyond the glittering surface of his seemingly endless flow of words. Prout’s ostensible purpose in the play is to find Mangan and enlist him for a literary project involving poetic translation. Translation is a central motif of the play and provides some of its most energetic moments.

Almost from the beginning, the shadow of events in the outside world intrudes into the play, initially through Prout’s obsessions with his literary and political bugbears, Thomas Moore and Daniel O’Connell. The smooth-talking cleric of the play fits rather well with some of what we know about Francis Sylvester Mahony. An effortless versifier and a good linguist, Mahony’s Father Prout (only one of his literary alter egos) specialised in producing Latin and French translations of contemporary poems, notably Moore’s melodies, which were comically presented as the originals in The rogueries of Tom Moore. The charge of plagiarism against Moore was more than just comic fun, however. Mahony resented Moore for his support for Daniel O’Connell, to whom he was always hostile and whom he satirised viciously in ‘The Lay of Lazarus’, written in 1845:

Hark, hark, to the begging-box shaking!

For whom is this alms-money making?

For Dan, who is cramming his wallet, while famine

Sets the heart of the peasant a-quaking.

The figure of Mangan, played by Mark O’Regan, is in stark contrast to Father Prout. O’Regan’s Mangan, in characteristic conical hat, wig and dark glasses, is the poète maudit, broken down by addiction to alcohol and opium but veering often in the direction of bathos. Mangan’s suspicions of Prout’s literary schemes gradually give way to engagement as the brandy flows.

The figure of Mangan, played by Mark O’Regan, is in stark contrast to Father Prout. O’Regan’s Mangan, in characteristic conical hat, wig and dark glasses, is the poète maudit, broken down by addiction to alcohol and opium but veering often in the direction of bathos. Mangan’s suspicions of Prout’s literary schemes gradually give way to engagement as the brandy flows.

With the arrival of Poe as the third visitor, the poetic trio is complete. Like the other two characters, Poe is something of a caricature. He is stereotypically American, swaggering about the stage like a dark villain from a Western, complete with gun, shocking the diplomatic Mahony and the protective barmaid and sharing his pouch of opium with Mangan.

Francis Sylvester Mahony (a.k.a. Father Prout) now a fairly obscure figure in Irish literary history, is still remembered as the author of ‘The Bells of Shandon’.

He introduces a note of energy and violence into the play, balancing the mellifluous Prout and the cryptic Mangan.

The interaction of the four characters on the small set at a sometimes terrific pace is a fine

piece of directing. The comic interaction is balanced by the introduction of darker themes from the poetry: an engaging series of exchanges sparked off by Mahony’s recitation of his translations of the Odes of Horace, while the tragic vision of Mangan’s versions of German and Irish poetry, the darkness of Poe’s poem ‘The Raven’ and the syrupy nostalgia of ‘The Bells of Shandon’ provide a brisk and effective succession of poetic moods. Always lurking in the background is the sense that these escapades are being acted out in the context of the enormous catastrophe of the Famine taking place outside The Bleeding Horse.

The darkening atmosphere of the second act, when Poe contemplates suicide and Mangan encounters the woman he was unable to marry, is less engaging than the serio-comic ecapades of the first. Even Father Prout is given a tragic past by the playwright, who introduces the death of a young student as the reason for the end of Mahony’s career as a Jesuit. In reality nobody died, but Mahony was forced to resign after allowing the senior class at Clongowes to become incapably drunk on an excursion to Celbridge in 1832.

Bleeding poets is an interesting example of dramatic fiction toying with the counter-factual—setting up an imaginary encounter between three contemporaries and exploring themes from the literary and social history of the 1840s. These themes are in a sense timeless and universal, linking the modern audience to the past and connecting three disparate writers to each other. The play’s entertainments and diversions also raise the question of the connections between the creative world of poetry, the mental anguish of the individual poets and the contemporary tragedy of the Famine that is happening offstage.

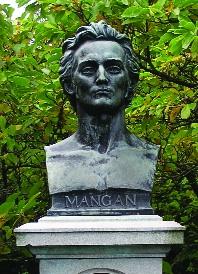

Poe (above) and Mangan (Oliver Sheppard’s bust in St Stephen’s Green), who both died relatively young and in broken health in 1849, might well have sparked off each other in an imaginary meeting.

Eamon O’Flaherty lectures in history at University College Dublin.