The Scullabogue Massacre 1798

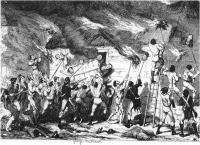

Published in 18th–19th - Century History, Features, Issue 3 (Autumn 1996), The United Irishmen, Volume 4 Few events in modern Irish history, especially in the history of revolutionary nationalism, haunt the imagination like the massacre that took place in the townland of Scullabogue in southern County Wexford on 5 June 1798. The killing of well over a hundred government supporters by rebels has been immortalised in the illustration that George Cruickshank produced for William Maxwell’s narrative of the rebellion, published in the middle of the last century. This, along with the vivid descriptions of other historians in the last century and of Pakenham in this, have immortalised the event in the Irish historical consciousness.

Few events in modern Irish history, especially in the history of revolutionary nationalism, haunt the imagination like the massacre that took place in the townland of Scullabogue in southern County Wexford on 5 June 1798. The killing of well over a hundred government supporters by rebels has been immortalised in the illustration that George Cruickshank produced for William Maxwell’s narrative of the rebellion, published in the middle of the last century. This, along with the vivid descriptions of other historians in the last century and of Pakenham in this, have immortalised the event in the Irish historical consciousness.

Raw brutality

The massacre occurred in a farmstead that was located at the foot of Carrickbyrne Hill, the main campsite of the southern division of the Wexford rebel army in the early days of the insurrection. The main body of that army had gone six miles to the west the evening before, to attack the town of New Ross, and had left a guarding party in charge of their loyalist prisoners. The next morning, as the battle for New Ross raged between government and rebel forces, they hauled close to forty men out of the dwelling house of the farmstead and shot them, four at a time, on the lawn. At the same time, other rebels attacked a larger group of prisoners being held in other parts of the farm and drove them into a large barn; there they shot at them and piked them until some of the prisoners slammed shut the barn doors. Then the guards set the building on fire. Inside, panic broke out. Between trampling, smoke and flames, all of those in the building died. The victims included men of all ages, a number of women, and several children. Most of them were Protestants, although around twenty are claimed to have been Catholics. There were many atrocities that summer, perpetrated by both sides, but none can match Scullabogue in terms of raw brutality. It was the single largest case of mass murder, by either side, and, very significantly, it was the only case in which rebels killed women and children. Beyond that, it was the only major atrocity associated with Wexford rebels from the area to the south of the Slaney. In more than one way then, it stands out as a kind of grim aberration.

Efforts to reconstruct the circumstances surrounding the massacre and to detail the killings themselves are hampered by lack of evidence. Eyewitness accounts of the massacre are few. A number of depositions, taken from the relatives of victims, were transcribed by Sir Richard Musgrave and published three years after the event, and these give us some insight. In addition, the records of several of the court martial trials of individuals accused of having taken part have survived. We also have the very vivid accounts of the event on the loyalist side written by Sir Richard Musgrave and George Taylor. Both accounts appeared in its immediate aftermath and both are based on evidence collected from those indirectly familiar with it. On the ‘pro-rebel’ side we have the memoirs of Edward Hay and Thomas Cloney. Neither was present at the killings either but Hay travelled the county in the year or so after the rising and talked to those generally familiar with it, Scullabogue included. Cloney spent the day of the battle in New Ross, where he took a prominent part in the fighting, and returned to Carrickbyrne the next morning. His account is chiefly valuable for the details it provides of the battle. Most critical of all is the very detailed narrative of the battle of New Ross compiled by James Alexander, a former officer in the British army and a seemingly fair-minded observer. His version of events, more than any other, has a genuine ring of truth about it; he was a loyalist, tried and true, but it is clear that he also disapproved strongly of the abuses to which soldiers in the New Ross garrison resorted before, during and after the battle.

Efforts to reconstruct the circumstances surrounding the massacre and to detail the killings themselves are hampered by lack of evidence. Eyewitness accounts of the massacre are few. A number of depositions, taken from the relatives of victims, were transcribed by Sir Richard Musgrave and published three years after the event, and these give us some insight. In addition, the records of several of the court martial trials of individuals accused of having taken part have survived. We also have the very vivid accounts of the event on the loyalist side written by Sir Richard Musgrave and George Taylor. Both accounts appeared in its immediate aftermath and both are based on evidence collected from those indirectly familiar with it. On the ‘pro-rebel’ side we have the memoirs of Edward Hay and Thomas Cloney. Neither was present at the killings either but Hay travelled the county in the year or so after the rising and talked to those generally familiar with it, Scullabogue included. Cloney spent the day of the battle in New Ross, where he took a prominent part in the fighting, and returned to Carrickbyrne the next morning. His account is chiefly valuable for the details it provides of the battle. Most critical of all is the very detailed narrative of the battle of New Ross compiled by James Alexander, a former officer in the British army and a seemingly fair-minded observer. His version of events, more than any other, has a genuine ring of truth about it; he was a loyalist, tried and true, but it is clear that he also disapproved strongly of the abuses to which soldiers in the New Ross garrison resorted before, during and after the battle.

Round-ups of loyalists not unusual

What then were the circumstances surrounding the massacre and what does the context of the event tell us about why it may have taken place? The first thing we must note here is that the creation of a make-shift prison camp at Scullabogue was in itself not unusual. It was common for rebel divisions, once they established themselves at a strong-point, to send parties out into the surrounding countryside to round up people they suspected of pro-government sympathies. This happened in the area around Enniscorthy and it also took place in and around Wexford Town and Gorey. Those rounded up were mostly Protestants, although some Catholics were held too. While there may have been a sectarian undertone to the process everywhere, it is noteworthy that some of the rebel officers who ordered these sweeps and some of the rank-and-file who took part in them were themselves Protestants. In most places those seized were not initially harmed, although the rebel units based on Vinegar Hill executed several men each day, (usually two or three a day), over the course of the four weeks they held the county. These killings normally followed a period of incarceration in a brewery at the foot of the hill and a trial at its summit. There were eventually killings at Gorey and Wexford Town too, but they took place in the final days of the rebel regime when panic had invaded their ranks and when internal factional struggles caused imprisoned government supporters to be sacrificed.

The process of rounding up prisoners in the vicinity of Carrickbyrne Hill followed roughly the same pattern as elsewhere. The rebels established a camp there on 1 June, in preparation for their anticipated attack on New Ross, and over the next two days small parties went out into nearby townlands and villages and arrested well over a hundred people. Most of those taken came from inside a triangular area stretching from Foulkesmills to Adamstown to Fethard, that is, from the areas to the north, south and east of the camp. The fact that loyalist families in townlands to the west of the hill had had time to escape to New Ross before the rebels arrived in the area probably explains why so few of them were picked up.

The Battle of Ross-‘One rebel, emboldened by fanaticism and drunkedness, advanced before his comrades, seized a gun, crammed his hat and wig into it, and cried out, “Come on, boys! her mouth is stopped” At that instant the gunner laid the match to the gun, and blew the unfortunate savage to atoms’ – W.H. Maxwell, History of the Irish Rebellion in 1798(London 18445), footnote p.118. George Cruiksank was at the hight of his fame when he drew the book’s technically brilliant illustrations. These heavily propagandist works paved the way for the brutish simian ‘Paddy’ which was to become the British

stereotype of the post-famine period.

The arresting party

The rebels who conducted the arrests were mostly from the locality in which they were operating and knew well those they had taken to the prison camp. We have the names of thirty-two individuals who carried out the sweeps. They came from a widely scattered area around the camp but an usually large number came from the townland of Kilbride, just north of Fethard. A significant number also came from the villages of Saltmills, Fethard and Tintern. Most seem to have been tenant farmers, although there was a scattering of labourers and artisans among them too.

Three rebels were especially prominent in the round-up and they represent something of a cross-section of the rebel officership in this part of the county. The most important of them was Michael Devereux of Battlestown, a townland about three miles west of the campsite. He led rebel parties to the villages of Tintern and Fethard on at least three occasions over those early June days. He was part of the larger Devereux connection, descended from Old English landlords who had lost their estates in the seventeenth century. In 1798 his family still held the entire townland of Battlestown, about six hundred acres, and, remarkably, still held it in 1810, even though he was transported for his part in the rebellion. As a member of the Catholic middleman class of south Wexford, Devereux is typical of the rebel officer corps from that part of the county and his involvement in the round-up of suspected government supporters is not surprising.

Even more interesting are Joshua Colfer of Fethard village, a maltster, and a John Houghron of the village of Tintern, a stone mason. The evidence of the depositions suggests that these two men led rebel search parties also and came through their home villages several times looking for suspects. Significantly, among those arrested and harassed by Colfer was the Clarke family of Fethard, his former employers. For his part Houghran operated mostly in and around Tintern and those who were prominent in his party included a tailor and a labourer.

The social status of rebels involved in the round-up may be quite significant. Much of south-west Wexford was in the hands of only a few large landlords. Two of these, the Loftus and Tottenham families, were closely associated with the conservative cause in the politics of the 1790s, while the other two, the Colcloughs and Leighs, had once been Catholic and were still associated with the liberal side of local politics. Tenant farmers are almost certain to have been drawn into the maelstrom of the liberal/conservative struggle in such an area. To add to a very tense and highly politicised situation, three small Protestant colonies had been established the villages of Tintern, Old Ross and Fethard earlier in the eighteenth century and these had remained very prominent pro-ascendancy enclaves up to the 1790s; this was especially true of the Old Ross settlement which was an exclusively Palatine Protestant community, located on a small tract of land owned by the Rams of Gorey, a steadfastly pro-ascendancy family. If we consider the political and sectarian symbolism of such communities, and the likelihood that economic rivalry surely developed between craftsmen and labourers of both religions in their vicinity, then it is not surprising that Catholic artisans and labourers would be active in the campaign against such people. Added to any radical or revolutionary agenda, in other words, was a local social and sectarian agenda, fuelled in large part by economic rivalries.

Government atrocities at New Ross

The more immediate circumstances of the massacre are confusing but the fragments of evidence available allow us to untangle them to some extent. Perhaps the most important thing about it is its connection to the battle of New Ross, only six miles away. The rebel attack on the town came at sunrise, 4.05 am according to the official calendar of 1798. According to Alexander’s account fighting reached into the heart of the town by six or seven o’clock. Government troops conducted the first of several counter-attacks in the next hour or two, possibly as early as eight o’clock but certainly by nine.

During these attacks (and there is ample evidence from Alexander to support this), soldiers took to systematically killing captured and wounded rebels. This was not unique to them, both rebel and government forces had done so before but, in the middle of this indiscriminate slaughter, one group of soldiers surrounded and set fire to a large house in Mary Street in which about seventy wounded rebels were lying. They prevented all but one man from escaping and Alexander claimed the screams of the terrified doomed men could be clearly heard, despite the noise of the

battle, over much of the town.

The issue of timing is critical here. The only witness who specifies the time at which the massacre began in Scullabogue, places it at between nine and ten o clock that morning. If the burning of the house in New Ross took place as early as 8.30 or even as late as 9.30, there was ample time for an incensed rebel to ride eastwards to Scullabogue with orders to kill all the prisoners, justifying this by an appeal to what had just taken place in the streets of New Ross. The only men in a position to recount what happened in the hours before the massacre began that

morning, Cloney and Hay, strongly suggest that Bagenal Harvey and the other rebel commanders had no connection to the event and even most loyalist historians seem to concur with this. The consensus instead is that retreating rebel units carried back the instruction to kill the prisoners and that the order came from somewhere other than the rebel commanders. The commander of the guarding party was a Captain John Murphy of Loughnageer, a nearby townland. He apparently refused early instructions to kill the prisoners, but eventually, after messengers had come from the direction of New Ross with orders to put them all to death for the third time, he agreed and told his men to proceed.

What happened once the order was given is not quite clear either. From the evidence we have though we can assert with some confidence that the kind of frantic mob scene depicted in Cruickshank’s illustration did not occur. Instead, it appears that around twenty or so rebels conducted t

he entire massacre while most of the guarding party stood about and watched. The killings were not carried out hurriedly, therefore, but were conducted in a chillingly methodical fashion; this is especially true of the executions on the lawn in front of the farmhouse.

The perpetrators

Most of the men who actually did the killing can be identified, and a profile of the group suggests some surprising features. Of the seventeen rank-and-file rebels which the depositions link directly to the slaughter, three, John Ellard, Robert Mills and John Turner, were Protestants; all three later claimed that they acted out of fear for their own lives (a common claim by former rebels in the years afterwards). Mills provided detailed evidence of the activities of those around him at the court martials and seems to have been set free by way of payment for his evidence, this in spite of the fact that he admitted hacking at prisoners trying to escape from the barn with his pike and striking a woman prisoner so hard with the weapon that it bent. Five, Patrick Furlong, Patrick Kerrivan, Michael Quigley, Daniel Sullivan, and John Tobin, were present at the killings, carried weapons at the time but were not actually seen to shoot or pike prisoners or set the barn on fire. Furlong and Sullivan were executed; Quigley and Tobin—who was about sixteen years of age—were transported; the fate of Kerrivan is unknown.

The remaining nine men, along with Robert Mills, were the hard core of the killers. This group consisted of two sets of brothers, John and Thomas Mahony and Nicholas and Thomas Parle. There was also Matthew Furlong (who may or may not have been related to a Matthew Furlong of Templescoby who was among those shot by soldiers in cold blood that morning in New Ross) and John Keefe, James Leary, Mitchell Redmond, and Michael Murphy. All nine were accused of having shot or stabbed prisoners at the door of the barn and three, Furlong, Leary and Murphy, were identified as having set the straw roof of the barn on fire. All nine were executed, a few in the late summer of 1798 itself, but most in the summer of 1799 and in the spring of 1800.

There were a few other people associated with the incident whose exact role is unclear. One deposition claimed that rebel officers Nicholas Sweetman of Newbawn and Walter Devereux of Taghmon were present. The evidence is not strong but Devereux was alleged to have praised the action later that day. He was captured a few weeks after the rebellion in Cork as he tried to take ship for America; the authorities hurriedly tried and executed him. Even more intriguing is the case of Father Brien Murphy, a suspended priest who lived in Taghmon and who was claimed to have been the one who sent word to kill the prisoners. There is reason to believe that the priest was in fact involved; several sources mention him in this role and even James Gordon, the widely respected Protestant historian of the rebellion, points an accusing finger. Surprisingly, though, Murphy somehow escaped the worst of the counter-revolutionary terror and as late as 1803 we find him asking Bishop Caulfield, the Catholic bishop of Ferns, to believe his promises of good behaviour and to allow him to administer the sacraments. We can only conclude that he went into hiding while the hunt for former rebel officers was underway and came out in the open a year or two later and survived partly because of his connection with the Church.

Conclusions?

What conclusions can we draw from this cursory summary of the evidence? We must first acknowledge that the rounding up of suspected government loyalists was common practice everywhere in Wexford during the rebellion, and the killing of prisoners was not unknown either; in this sense what happened at Scullabogue was part of a larger pattern, albeit on a larger scale and carried out in an especially brutal manner. Beyond this though, the evidence strongly suggests that the killings took place as an immediate reaction to atrocities in the battle of New Ross, raging six miles away. It suggests that they were ordered by what can only be described as renegade officers and carried out hesitantly by only part of the guarding party and not by the entire unit. Finally, while it is undeniable that sectarian hatred had some part to play in the affair, I suspect that as we learn more about the crime and the people who carried it out, it will be seen to fit the larger pattern of social and political violence that was characteristic of Ireland at large and the Atlantic world as a whole in the era of the French Revolution; the sectarian dimension will then come to appear far more incidental to the affair than it has hitherto seemed.

Daniel Gahan lectures in history at the University of Evansville, Indiana.

Further reading:

T. Pakenham, The Year of Liberty: the great Irish rebellion of 1798 (London 1969).

E. Hay, History of the insurrection of the county of Wexford, 1798 (Dublin 1803).

D. Gahan, The People’s Rising: Wexford 1798 (Dublin 1995).

J. Alexander, A succinct narrative of the rebellion in the county Wexford (Dublin 1800).