Returning to its “old form”

Published in 18th–19th - Century History, Features, Issue 2 (Mar/Apr 2007), Volume 15

The Ashes, Cromwellians with an upland seat in the Glen of Aherlow, had twin sentry posts installed at the entrance to their small estate, evidence of the region’s ongoing insecurities.

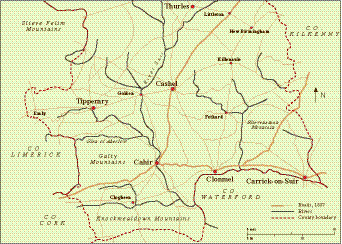

Tipperary in the eighteenth century was a county where a larger than average portion of the countryside remained in Catholic hands and where, consequently, tensions between the Protestant establishment and leading Catholic families remained high. The single greatest reason for this was the failure of the colonial administration to convert sufficient branches of the Butler dynasty—the largest landowners in County Kilkenny and amongst the largest in County Tipperary—to the established church. In Tipperary especially these families were vehemently anti-establishment, and persisted in directing many of their younger sons and daughters into religious orders on the Continent. The county had a large number of Catholic ‘gentleman tenants’, who leased from the remaining gentry of their denomination and Protestants alike. This strong Catholic landed interest, which was at its most powerful in the southern districts of Tipperary, interfaced with an active Protestant interest in the north-west and in the south, along the lower reaches of the River Suir and its tributaries. Indeed, the county constituted an almost physical frontier between the largely Butler lands stretching from Kilkenny across Tipperary to Cashel and Cahir and the ‘quite rabid’ flanking regions of predominantly Protestant landownership on either side.

Ongoing insecurities

In the eighteenth century Protestants of all ranks and creeds in general still viewed Catholics with the greatest distrust. Their spiritual link with the pope in Rome caused them to be termed ‘popish’, ‘papist’ or ‘romish’ by members of the Protestant denominations. Catholic diocesan clergy and religious orders were compared with swarms of insects and portrayed as less than human, owing to fear of their powerful influence over the ordinary people. Immense social pressures were brought to bear, in the first half of the eighteenth century especially, on Catholic clergy to convert, and a few serving in key towns were induced to do so. Surviving sources reveal that local government despaired of ever having sufficient armed force with which to censor priests. Several note the injuries suffered by companies of soldiers, attacked by vast stone-throwing mobs, while transporting priests to prison. The intimidation experienced by High Sheriff Jonathan Lovett was such that he left his home at Kingswell, near Tipperary, to dwell in the safety of the town itself. The Ashe family, Cromwellians with an upland seat in the Glen of Aherlow, had twin sentry posts installed at the entrance of their small estate. These ongoing insecurities led to an increased military presence in the region.

The number of Catholic aristocratic and gentry families dwindled over the first half of the eighteenth century as penal legislation impeded the transfer, intact, of their estates from one generation to the next. Their wealth and status remained significant, however, with several estates surviving virtually intact and many more continuing as head tenants on their former estates. Already, by the mid-1730s, numerous Catholic families of aristocratic, gentry and mercantile background were subscribing to contemporary publications.

These voluntary subscription lists provide a window into Catholicism in this period that belies the myth of the total degradation of leading families of that denomination, while revealing an availability of surplus funds for philanthropic and leisurely pursuits. There are several examples from this period, such as Botanalogia Universalis Hibernica (1735) and Zoologia Medicinalis Hibernica (1739). The former, printed in Cork, drew subscriptions from all over Munster and also County Kilkenny. Of some 370 subscribers, a third were identifiably Catholic, a remarkable statistic and indicative of the lifestyle that many dynasties were able to maintain. In south Tipperary there were nine subscribing Catholic households and seven Protestant; the former outnumbered the latter, in terms both of subscribing households and of copies taken.

Catholic head tenants

In addition to these key survivors among the gentry, a numerous group existed at head-tenant level, with the majority located in the area stretching from south of Cahir to north of Cashel, and also in the hinterland stretching northwards from Clonmel and Carrick-on-Suir. McCarthy of Springhouse and Keating of Garranlea, noted priest-protectors, each held lands extending to several thousand acres, which brought them to the attention of the travel writer Arthur Young in the 1770s. The gentry-style refinement of these households can be further observed in their subscribing to notable publications as early as the 1730s. Keating of Knockagh, Nagle of Garnavella and Mulcahy of Corabella dominated the head tenantry on the Butler (Cahir) estate, where the bulk of the tenants were Catholic.

Throughout the south riding, several former landowners whose ancestors had been expropriated in the seventeenth century maintained their position by securing advantageous leases. A sympathetic landlord was essential. In 1729, in addition to bequeathing 30 shillings towards the upkeep of Cahir Mass-house, Robert Keating of Knockagh bequeathed a young grey mare to Lord Cahir’s eldest son as a token of his affection. This flattery obviously paid dividends, for by 1767 the Keatings held over 3,000 acres on lease. Kinship to the landlord was another distinct advantage, as evidenced by the presence of Butler families renting substantial farms on long tenancies in the manors of Rehill and Castlegrace on the Cahir estate. Between them four families held over 900 acres on favourable terms.

Catholic church territorial renewal

Three successive members of the Butler family held the premier Catholic church office in Munster, the archbishopric of Cashel, in the period 1712–91, which is a measure of the confidence the church placed in the religious pedigree of the various branches of this family as well as their ability to increase the perceived respectability of the denomination among Protestants.

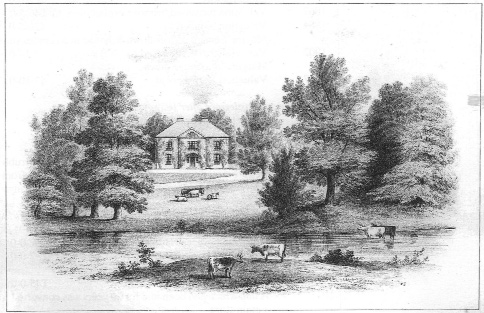

Garnavella, near Cahir, seat of the Nagles, one of many Catholic head tenants in the region who secured advantageous leases.

Christopher Butler, of the Kilcash branch, was archbishop from 1712 to 1747, during which time he held mass ordinations at chapels on the Mathew estates at Thurles and Thomastown for a total of 50 priests. His successor, Archbishop James Butler I, was of the Dunboyne branch, while Archbishop James Butler II was of the Ballyraggett, Co. Kilkenny, branch. A surviving book of diocesan visitations undertaken by James Butler I in Cashel and Emly is instructive. It gives the definite impression of a church going through a period of reform and renewal, not a church existing as a secret underground force struggling for survival, a phase that the archbishop’s secretary, Dr John Butler, parish priest of Ardmayle, noted as returning to its ‘old form’. It shows that rural church buildings, although modest in size and furnishings, were numerous, and that improvements were continually in progress, with several newly built or renovated chapels noted in the years covered by the reports. Even villages had decent chapels, as at Killenaule by 1754, where a chapel was built in the form of a ‘T’, with a stone wall 7ft high, four gable ends, well thatched, six glass windows, altar, rails and pulpit of deal boards, and three large stone cisterns to hold holy water. In this largely rural area, chapels were predominantly barn-like structures with clay floors, whitewashed stone walls and a low thatched roof.

Though the church was still lacking in material resources, it was becoming better organised, with a wide parochial structure well established by the 1750s. The Mass-houses of the towns were significant buildings—particularly those of Clonmel and Tipperary—and were envied by rural Protestants, many still lacking a church or resident rector. The writer Charles Smith visited Clonmel during the 1750s, where he noted that ‘the Romanists have a very neat mass-house, pleasantly situated on the side of the Suir and adorned with a grove of trees, it being a few years ago splendidly rebuilt with many others in Munster by large contributions raised in Spain’. A side view of this building, drawn in the 1840s towards the end of its life, is depicted on p. 27. Although just one side of the substantial ‘T’-shaped building can be seen, its size and durability are obvious. There were a number of very large leaded glass windows, a slated roof and three galleries, all accessed by outside steps, very much in the vernacular style of architecture favoured by the Presbyterians and Catholics during the eighteenth century. In addition, an impressive array of vaults contained the remains of previous parish priests.

Towerless Catholic chapels

In rural parishes, Catholic chapels were often towerless and cruciform, erected on sites that had more to do with the convenience afforded by an expanding arterial road network than with the intrinsic appeal of the many historic Christian sites. In rural districts of south Tipperary they gathered new villages around them; in the towns, however, chapel-building was of a far more affluent nature. In 1824 the chapel erected in 1790–1 at Cahir was noted as a large plain building with a handsome lofty spire. The site at Cahir had no previous ecclesiastical significance, but at Cashel and at Thurles the site of both the Mass-house and the succeeding chapel was on or adjoining the site of the monastery of a religious order. At Cashel, the new chapel of 1795 was built on the site of the Franciscan friary, but this was insufficient to quell the dissatisfaction of the parishioners. Such was their sense of identification with and attachment to the old thatched chapel adjoining the ruined Dominican priory in Chapel Lane that it was razed in 1798 on the orders of the parish priest, in defiance of their opposition to the new site and building in Friar Street, to which he had contributed substantially from his own estate.

The territorial organisation of the Catholic church at this time was still largely that created in the later seventeenth century, and parish boundaries were significantly redrawn in just four locations within south Tipperary in the period prior to the mid-nineteenth century.

Christopher Butler of Kilcash, Catholic archbishop of Cashel from 1712 to 1747-two other Butlers, albeit from different branches, held the office until 1791. (St Patrick’s College, Thurles)

![An 1840s drawing of the Mass-house at Clonmel, ‘splendidly rebuilt [in the mid-eighteenth century] with many others in Munster by large contributions raised in Spain'. Note the large leaded windows and slated roof.](/wp-content/uploads/2013/02/59.jpg)

An 1840s drawing of the Mass-house at Clonmel, ‘splendidly rebuilt [in the mid-eighteenth century] with many others in Munster by large contributions raised in Spain’. Note the large leaded windows and slated roof.

Three of these boundary revisions came about through a realisation that current arrangements were too extensive to serve the needs of the parishioners. Two other boundary revisions reflected population growth along the southern county boundary. A final boundary realignment, also directly related to a growing population, involved the building of a chapel of ease in the county town of Clonmel. All these developments involved expansion or improvement. Only one Mass-house was abandoned owing to falling population.

The strongest adherence to the site originally chosen for the thatched Mass-house occurs in the southernmost parishes, particularly in the heavily Catholic jurisdiction of the diocese of Waterford and Lismore. In the great swathe of territory to the north of this area—the jurisdiction of the archdiocese of Cashel and Emly—retention of the original Mass-house site was the exception rather than the rule. This would seem to indicate the existence of a generally more favourable climate for the prominent placement of Mass-houses in the early eighteenth century in the southernmost parishes. Here, a large number of comfortable Catholic tenant farmers and merchants, in combination with the survival of a number of gentry, allowed the Catholic denomination to establish itself on favourable sites at an earlier period than their brethren in Cashel and Emly archdiocese to the north.

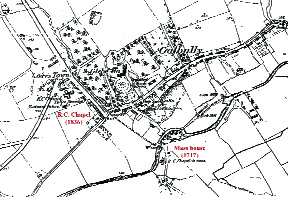

The premier local example of chapel site improvement occurred in the border village of Galbally, in the archdiocese of Cashel and Emly, where the thatched cruciform Mass-house of 1717—separated from the village by a river and located at the end of a side street—was superseded in 1836 by a large slated chapel and schoolhouse. This was symbolically placed at the heart of the old plantation settlement of Lowe’s Town. The glebe-house demesne, complete with medieval ruined church, still occupied the ancient ecclesiastical site of the settlement. The extent of the identification of the entire settlement with the Catholic church from 1836 led the Anglican establishment to relocate its parish church to the village in the early 1850s, on a prominent site at the street junction next to the entrance to the glebe-house. The estate church of the Massy family at Duntrileague, which had served the parish union since the Restoration, was then dismantled.

The village of Galbally-an example of Catholic chapel site improvement. (Ordnance Survey Ireland)

Catholic Mass-houses were generally thatched structures, and prior to the building of the first modern chapels in south Tipperary only the important urban parishes of Clonmel, Carrick-on-Suir and Tipperary possessed a slated Mass-house. In south Tipperary the thatched roof still prevailed on all but seven of the 55 chapels in existence in 1800. A striking indicator of the seismic transition from thatched to slated chapel in little more than three decades is the fact that by 1834 only eight parishes still had thatched chapels. They were predominantly backward, rural parishes in which this deficiency was not remedied for many decades. It is significant, however, that all but one of these churches lay within the bounds of Cashel and Emly, with its significant and enlarged Protestant rural communities and with Catholic tenant farmers of a less affluent nature than their brethren in the diocese of Lismore to the south.

Mass-houses, meeting-houses and churches

In the first half of the eighteenth century, prior to the easing of penal legislation, Catholic places of worship were termed ‘Mass-houses’, while those of the Protestant dissenters were called ‘meeting-houses’. They shared a second-rate status and were invariably located in side streets and less desirable obscure locations. In the last quarter of the century, both were somewhat upgraded in the eyes of the establishment as ‘chapels’, while the term ‘church’ remained reserved for the buildings of the established church alone.

The location of Catholic chapels was determined by a number of factors, such as site sponsorship by a local family and the cooperation or otherwise of the principals of the local Protestant establishment. Surviving Catholic gentry and head tenants had been most important in the provision of the rudimentary Mass-houses of the early eighteenth century, as at Cahir, where the Mass-house stood by the demesne gates of the Butler estate, and at Kilcash and Thomastown, where it was within the demesne itself.

Religion and rivalry

Villages and towns were battlegrounds between the two traditions. The Catholic chapel was usually located well away from the Anglican church, reflecting the deep-seated dualism common in a colonial setting. Indeed, by the mid-nineteenth century the location of various institutional buildings in many towns and villages reflected both the dominance of the Anglican establishment and the subordinate status of the Catholic majority. This concept of churches at opposite ends of a village or town, gathering each to its own, often at the end of a single thoroughfare, underlined the powerful undercurrents that bedevilled this polarised society.

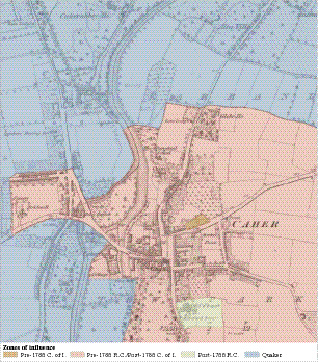

The dichotomy of the market square and fair green appeared to be a well-developed characteristic of villages and small towns that served as estate centrepieces. The square or main street displayed the planned arrangements of institutions and functions that satisfied the needs and tastes of the landlord, including his own townhouse, the market and courthouse, assembly rooms, church and school. In association with the fair green, on the other hand, were usually found the more casual and menial needs of the countryman: smithy, ball alley, pound, police barracks, bridewell, public house, medical dispensary, national school, ‘big chapel’ and priest’s house. The estate town of Cahir was unique in south Tipperary, and exceptional in southern Ireland, in that in addition to being a fine example of the above phenomenon it also developed three distinct denominational spheres of influence. A great swathe of territory to the north and west of the town was leased by the Quaker milling dynasties, with the country estates of Cahir Abbey (Grubb), Alta Villa (Going) and Mill View (Walpole) adjoining their family mills of Abbey, Suir and Cahir respectively. The great central zone was occupied by the Anglican establishment, with a church, parochial school, glebe-house, bridewell, police barracks, courthouse and market-place all adjoining the landlord’s seat, Cahir House.

The estate town of Cahir-an example of three distinct denominational spheres of influence. (Ordnance Survey Ireland)

The Catholic zone of influence was miniscule by 1840, with its chapel and national school boxed in on all sides by landlord-owned property. Ironically, this was a direct reversal of the influence enjoyed prior to 1788, when the sphere of Catholic interest adjoined the Quaker properties, leaseholders of a Catholic landlord, and the Anglican zone of influence was confined to its medieval churchyard.

Further evidence of competition for space between Anglican and Catholic institutional churches in the early nineteenth century can be observed on examination of the dates of construction or renovation of parish churches in both communities. It can be established that in eight south Tipperary parishes where Catholic chapels were built or rebuilt, the local Anglican establishment retorted—on average within five years—by substantially rebuilding or replacing their own premises. This competition was even more pronounced in a further four parishes, where within a year of the Anglican parish church being built or rebuilt the local Catholics responded even more promptly by providing new church premises, usually within four years. In some rural Anglican parishes, the insecurities resulting from the relaxation of penal legislation from the 1770s led to an upgrading of the visibility of the parish church, usually with the addition of a tower or steeple. The success of the Catholic church in occupying central urban sites in the post-emancipation period also prompted the movement of the Anglican churches from medieval sites to the settlement itself.

Cordial relations

Despite this competition for space, cordial relations were in evidence in several parishes. At a local level, theological issues often had little bearing on inter-church cooperation; in the heavily Catholic town of Carrick-on-Suir, the chief builder of the new chapel was Richard Clarke, ‘a good, honest Protestant’. In 1819 at Clogheen, following the completion of the new parish church, the vestry resolved that the materials from the old church be given in trust for the use of the new Catholic chapel intended to be erected in the town. The exclusion of the steeple from this ecumenical gesture signifies, however, that the Anglican community, while still comfortable in their ascendancy, were averse to being lorded over by Catholics, most particularly with materials of their own provision. The steeple at Shanrahan, a comparatively recent erection of 1793–4 that aimed to raise the profile of the established church on its detached medieval church site, one mile from the town of Clogheen, was instead left in position. Nevertheless, this gesture was of the utmost significance, given its location in a district that had seen some proselytising during the 1740s and widespread anti-establishment violence from the 1760s, resulting in the execution in 1766 of the parish priest, Revd Nicholas Sheehy, at the peak of sectarian tensions.

David J. Butler teaches at the Department of Geography, University College Cork, and Department of History, University of Limerick.

Further reading:

D.J. Butler, South Tipperary, 1570–1841: religion, land and rivalry (Dublin, 2005).

W. Nolan and T. McGrath (eds), Tipperary: history and society (Dublin, 1985 and 1997).

T.P. Power, Land, politics and society in eighteenth century Tipperary (Oxford, 1987).

M. Wall, Catholic Ireland in the eighteenth century: collected essays of Maureen Wall (Dublin, 1989).