Pasteboard Perceptions

Published in 18th–19th - Century History, Features, Issue 2 (Summer 2002), Volume 10

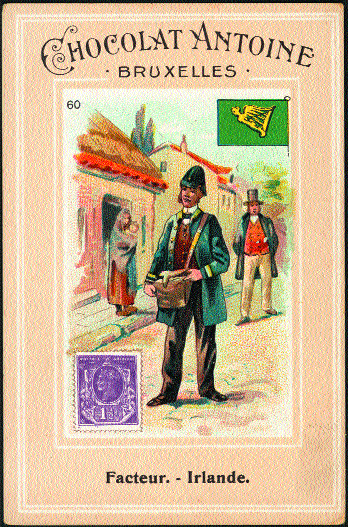

The Irish subject of this Chocolat Antoine of Brussels series, shows a village scene complete with helmeted postman and a shawled woman holding a baby.

In 1853 Aristide Bouciclaut—no apparent relation of the Irish playwright—hit upon a novel way of publicising his modest drapery shop, trading as Bon Marché, in the Rue de Sèvres in Paris. He produced an attractive card, printed by the relatively new process of chromolithography, depicting an elegantly aristocratic figure paying his respects to a blushing young lady. The key was the young lady—for the card was designed to appeal to the children who came with their parents to his shop and were presented with it together with a promise that it would be followed by a new one the following week.

Trade cards

The chromo was, in fact, the first of a set of six, and with its appearance a new collecting hobby was born. By the end of the century shops large and small both in Paris and the provinces, chocolate manufacturers, starch manufacturers, chicory sellers, umbrella makers, undertakers and the world and his wife were issuing cards in profusion. Formats varied according to the exigencies of packaging or other commercial imperatives, but a common size was 110 x 70mm or thereabouts, permitting effective display of the colourful obverse images. The reverse of the cards was either entirely devoted to an advertising message or carried an informative text relating to the subject matter which itself ranged far and wide, drawing in time on virtually every theme and topic known to the encyclopaedia and the almanac, supplemented by contemporary events such as the great Paris International Exhibitions of the latter part of the nineteenth century.

Printing by lithography—transferring the image from a specially prepared stone—had been invented by the Bavarian Alois Senefelder in Munich in 1796-9, and it was the German firm of chocolate and cocoa manufacturers, Stollwerck, founded in 1839, which first recognised the advertising value of the new process by printing attractive images on its wrappers, frequently employing the resources of the twelve-colour process. These package images evolved into a vast series of collectable cards, from 1897 issued with special albums in which to house them.

The meat extract company Liebi

The meat extract company Liebig, based in Uruguay and subsequently in Antwerp and originator of the familiar Oxo cubes, began issuing cards in the early 1870s and by 1974, when publication ceased, had circulated some 1,863 series, generally in sets of six. Liebig cards appeared in up to thirteen languages, including Flemish, Polish, Swedish, Danish, German and, rarely, English. Research and production standards were consistently high if the treatment of the subject matter (see below) was at times somewhat idiosyncratic.

Cigarette cards

While the popularity of the trade card was expanding exponentially in Europe a parallel development, originating in the United States, introduced a new, and equally collectable, advertising medium. The cigarette card developed from an initial plain stiffener for a packet but its value as a promotional item soon became apparent and from the 1880s onwards cards began to appear first with simple advertising messages and then with visually attractive images and issued in sets. While some mainland European countries were slow to adopt this new medium (Germany, for instance, did not issue cigarette cards in volume until after the First World War) they became extremely popular in Britain and her colonies (including Ireland) and in such diverse locations as Denmark, the Canary Islands, Egypt, Cuba, Argentina and Mexico, until the stringencies of World War II and the advent of political correctness in the matter of tobacco consumption induced their effective eclipse.

Irish subjects

As issues both of trade and tobacco cards increased throughout the period under review the search for attractive and appealing new subjects grew more and more extensive. Early American and British smokers, being largely male, were offered pretty girls, dogs, military glory and sporting prowess on early cigarette cards, but the European trade card, reaching as it did a wider cross-section of the community, was from the beginning more wide-ranging in its choice of themes. It was thus inevitable that a number of the many series that ventured beyond the history, natural history, social mores, heraldry, husbandry or other domestic preoccupations of France, Germany or the many other individual issuing countries should at some point include Irish subjects within their conspectus. The selection of such material was nothing if not eclectic and its study offers an unusual insight into mainland European perceptions of Ireland through the period.

While it is possible to date with some accuracy the cards of major issuers such as Liebig, Stollwerck, Suchard or Bon Marché others, such as those offered by French provincial stores or manufacturers, present major difficulties in this regard. The problem is exacerbated by the fact that the specialist printers involved would originate designs which were subsequently sold to a substantial number of customers over a considerable period: Paris firms such as Laas, for example, produced cards which can be found with the names of companies not only in France but in Belgium and Spain and as far afield as the United States, Panama, Britain and Ireland. A series employing the common device of a blank square in the illustration in which a firm’s name could be overprinted was sold, for example, to John MacWilliams, Hosiers, of Dublin sometime in the early nineteenth century. This could in no way be described as Irish in subject matter, any more than the series featuring children in rural French scenes issued by the Compagnie Irlandaise, handkerchief manufacturers, of Paris.

Postman Pat?

The unlikely figure of the postman would, at this time, seem to have attracted the same kind of public admiration as the pop star of the present day, and a series featuring, and sometimes titled, ‘The Post in Various Countries’ appeared in many formats and under the imprint of many issuers, from those of Turkish and British cigarette manufacturers to French and German biscuit and chocolate firms, Dutch tea merchants and Spanish patent medicine purveyors. The originator must have made a small fortune in royalties, since in virtually all cases the identical artwork appears, if in a variety of sizes and formats. The Irish subject, as depicted in the version by Chocolat Antoine of Brussels, shows a gold harp on a green ground as the national flag, a 1 1/2 d. stamp of Queen Victoria, and a village scene complete with helmeted postman and a shawled woman holding a baby. [fig.1] Unlike those of some other issuers, this version of the series carries no informative text on the reverse of the card.

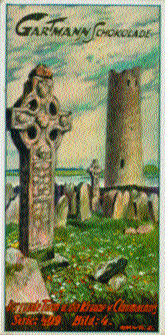

German chocolate firm Gartman’s romantic view of the High Cross at Clonmacnois.

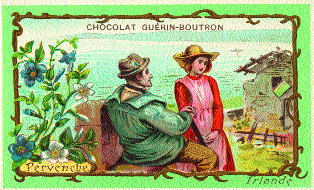

Chocolate manufacturer Guérin-Boutron’s early twentieth-century series, ‘Fleurs avec Pays d’Origine’-the Irish flower is, surprisingly, the pervenche or periwinkle.

Several series, including two by Liebig, were based on Swift’s Gulliver’s Travels.

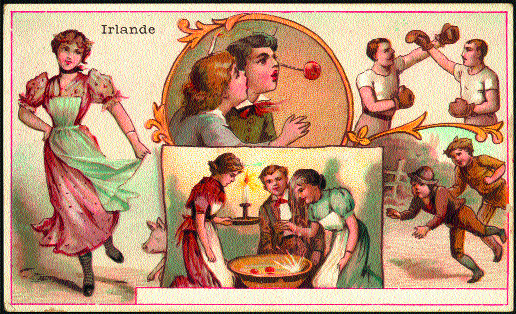

Irish pastimes of ‘La fíªte de Hallowe’ illustrated and described in ‘Sports & Divertissements du Monde’ (Bonzel-Haubourdin, proprietors of ‘Chicorée í la Bergére’).

The nineteenth century saw a steady stream of travellers from mainland Europe visiting Ireland and recording their impressions. Some, like Gustave de Beaumont (L’Irlande Sociale Politique et Religieuse, [1839]) or Johann Georg Köhl, who interviewed Bianconi, ‘king of the Irish roads’ in his Reisen in Irland (1843), were serious social enquirers. Others, such as the Baron E. de Mandat-Grancey, whose 1887 account was translated as Paddy at Home, could be described as being of the pig-in-the-kitchen school. Both of these approaches are reflected in card issues of the period featuring Ireland. In 1908 Liebig published a set under the title ‘Raccolti Vari’, depicting harvesting in various countries, the card relating to Ireland offering a highly romanticised impression of the potato gathering. [front cover] The following year the same company issued a series entitled ‘Divers Systèmes de Chemins de Fer’, both these sets appearing in several languages but not in English. Included in the latter was a view of the unique Listowel-Ballybunion monorail (1888-1924) which had attracted wide international interest. The card in this instance carried a text on the reverse which reads in part: ‘The monorail railway is often referred to as the rapid transit of the future, since even at a speed of 180 km an hour derailments are impossible. In Ireland several of these railways have been constructed…’ The Listowel-Ballybunion line, in fact, remained unique and nothing remotely approaching a speed of 180 kmh was ever achieved…or indeed attempted. The picture, be it noted, includes, besides an accurate representation of the locomotive and train, an admiring audience in the shape of a barefoot youth accompanied by a pig and a goat. The Lartigue, as it was popularly known after its inventor, also featured on a later German cigarette card series issued by Reemstma under the title ‘Bilder aus aller Welt’.

‘Lago de Glenda’

Some quarter of a century later, in 1935, Liebig devoted a complete six-card set to Ireland under the title ‘Attraverso L’Irlanda Pittoresca’ featuring Killarney, the Giant’s Causeway, the ‘Castello de Killemore’ (Kylemore) and the quaintly translated ‘Lago de Glenda’ (Glendalough). [fig.2] The emphasis, both visual and verbal, was certainly on the picturesque to the extent that the view of Killarney, for example, appears to have been plucked out of a much earlier era, whilst some of the ‘facts’ conveyed are equally bizarre: ‘…nel 459 essa fu evangelizzata de monaci bretoni e scozzesi tra i quali si trovava San Patrizio…’ [‘…in 459 it was evangelised by Breton and Scottish monks after which came Saint Patrick…’].

Rural Irish scenery appealed to several other issuers including the prolific German chocolate firm of Gartmann—which published a six-card series depicting highly romantic views of McGillicuddy’s Reeks, and the High Cross at Clonmacnois [fig.3]—and the Belgian firm of Planta (Killarney, Blarney Castle).

A set by Chocolat Poulain included Lally Tollendal, ‘baron de Tollendal en Irlande’ who led an Irish brigade at Fontenoy.

In its extensive ‘Collection Européene’, Suchard, the Swiss chocolate manufacturer, featured ‘La Chaussée des Géants’ with the information that ‘Le géant Finn Mac-Coul aurait construit la chaussée pour permettre à son rival Ecossais le géant Bolindonner, de traverser la mer sans mouiller ses pieds…’—an odd reversal of the usual version of the legend which has Finn building the causeway to get at his Scottish adversary. The Liebig card, already referred to, has a different version again. The rural emphasis is also apparent in a series of ‘Fleurs avec Pays d’Origine’ produced by the large chocolate manufacturer Guérin-Boutron early in the century. This shows a quaintly-attired couple at the seashore with, in the background, an archetypical ruined cottage. The flower in question is, somewhat surprisingly, the pervenche or periwinkle. [fig.4]

The urban Irish scene clearly had less appeal for Continental issuers, but a Danish card produced by Richs of Copenhagen in the 1930s offers a fully contemporary view of Dublin’s O’Connell Street complete with tram no. 87. The text supplies correctly the Irish name, Baile Átha Cliath, an accurate pocket history from the Danes (predictably) onwards and a summary of significant monuments including, as illustrated, ‘O’Connell, irsk Folkeforer og Statesmand…’ [‘Irish popular leader and statesman…’]. As for the people themselves and their customs, the game of hurling is described as ‘une sorte de hockey’ in a series devoted to ‘Sports Insolites’ [‘Unusual Sports’] by Jacques of Belgium; but even more unusual are the Irish Halloween (‘La fête de Hallowe’) pastimes illustrated and described in ‘Sports & Divertissements du Monde (Bonzel-Haubourdin, proprietors of ‘Chicorée à la Bergére’). These include, in addition to the familiar ducking for apples, the ‘jeu de Cochon’ in which a greased pig is released between the rows of players who attempt to capture it, ‘ce qui n’est pas facile à exécuter’. This card can be approximately dated by the fact that it describes Dublin as having a population of 245,000. The 1871 census gave a figure of 246,326, but the information on the card was probably not up to date.

Several series, including two by Liebig, were based on Swift’s Gulliver’s Travels but with no acknowledgement of an Irish connection. [fig.6] Similarly, a transport series by Pernot, the French biscuit firm, gives the origin of the fiacre carriage (named after St Fiachra) without referring to his putative origins. Irish-French connections were, however, better represented in a large set by Chocolat Poulain which included Lally Tollendal, ‘baron de Tollendal en Irlande’ who led an Irish brigade at Fontenoy. [fig.7] A similarly extensive biographical issue (c.1903), that by the still familiar grocery chain of Félix Potin, reproduced a striking photograph, by Reutlinger of Paris, of the young Maud Gonne, with a sympathetic if somewhat euphemistic account of her life-story to date (‘resolut d’employer tous les moyens en son pouvoir por améliorer le sort de ses compatriotes’).

Propaganda

Card issuers, both tobacco and general trade, were not slow to appreciate the propaganda, as distinct from the commercial, possibilities of the new medium. The colonising nations—Belgium, Britain, France, Germany and to a lesser extent the USA—produced series commemorating the spread of their respective empires and their successes in colonial wars, while newly-independent nations, such as Argentina, responded with cards depicting and describing their respective ‘freedom-fighters’, including, in the case of Chile, General Bernardo O’Higgins. Most of these series, assuming an acceptance of colonial expansion per se, were what might be described as benevolently propagandist. The First World War, however, saw a harsher tone develop, with a British cigarette manufacturer, for example, devoting a series of 140 to alleged German atrocities in Belgium; and with the subsequent rise of Nazism the propaganda potential was exploited to the full. In the early months of the Second World War the German tobacco firm of Reemstma issued a substantial series in several differing formats under the title ‘Raubstaat England’ [Robber-State England] which included several cards depicting Ireland’s fate at that country’s hands, from the Norman invasion which was responsible for ‘der lange Leidensweg des irischen Volkes’ [‘the long Way of the Cross of the Irish people’] to the Famine and the death—‘starb für Irland’—of Terence MacSwiney.

![‘Irland am Kreuz' [Ireland on the Cross] surrounded by the phantoms of women and children, crying out ‘O God, whom I have so long implored in vain, have you become an Englishman?'](/wp-content/uploads/2013/02/Pasteboard-Perceptions-8.jpg)

‘Irland am Kreuz’ [Ireland on the Cross] surrounded by the phantoms of women and children, crying out ‘O God, whom I have so long implored in vain, have you become an Englishman?’

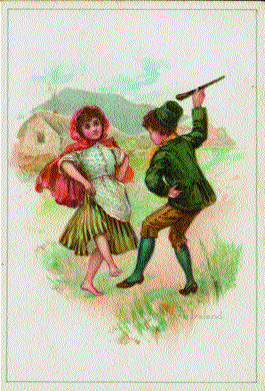

The abiding image of Ireland-he wielding a shillelagh, she shawled and barefoot.

As an added barb some of the texts were supported by quotations from England’s then allies including the French journals Le Monde Illustré and, bizarrely, Le Rire of 1899. The latter is quoted on a card entitled ‘Irland am Kreuz’ [Ireland on the Cross] which shows, in stark black and white in common with the rest of the series, the crucified female figure of ‘Erin’, surrounded by the phantoms of women and children, crying out ‘O God, whom I have so long implored in vain, have you become an Englishman?’[fig.8]

The visual appeal of heraldry, particularly in its frequent deployment of gold and silver, made the subject a popular one from the early days of card issues, and Irish arms and flag, in both its colonial and republican manifestations, appeared in several Continental series. The abiding image of Ireland, however, is perhaps best represented by a card which appeared in many series of ‘National Types’ on which a boy and a girl, he wielding a shillelagh, she shawled and barefooted, are dancing a jig in front of a thatched cottage with a Paul Henry mountain in the background. [fig.9] About this time Ireland itself was marketing a cigarette card series (1931) devoted to the construction of the transformative Shannon Scheme; but before the new message could get through the houses of cards, already shaken by new advertising media and methods, were to collapse before the whirlwind of world war.

Bernard Share is a writer and editor.