Neutrality: ‘the very essence of Irish independence’?

Published in 18th–19th - Century History, Issue 5 (September/October 2013), Platform, Volume 21

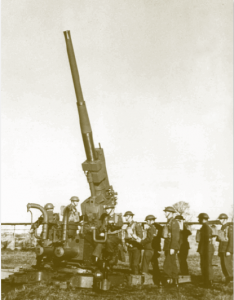

Irish Defence Forces manning a 3.7-inch Vickers heavy anti-aircraft gun. They were not shy about taking the offensive if required. At least three belligerent aircraft were shot down, and anti-aircraft batteries regularly opened fire on suspicious intruders. (Military Archives)

‘It rarely pays to get between a dog and a lamp-post’, remarked United States Secretary of State Cordell Hull on the virtues of neutrality. For Dante, ‘the hottest places in hell are reserved for those who, in times of great moral crisis, maintain their neutrality’.

Was Ireland right to stay neutral in the Second World War? Place yourself in the Long Fellow’s shoes and make up your own mind by reading the original correspondence from the wartime Department of External Affairs. The archives of today’s Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade reveal how Ireland’s senior diplomats and politicians saw the world of 1939 and how they responded to the fearful summer of 1940, when an invasion of Ireland appeared imminent.

Irish Naval Service motor torpedo boats—neutral Ireland actively defended its territory (and waters) during wartime. (Military Archives)

There is a real need to go to these sources and examine them, as Ireland seems to be increasingly ashamed of its wartime foreign policy but at the same time has forgotten why the state opted for neutrality. Reading the panels recently at the Army Museum in Stockholm showed Sweden grappling with the same questions about its 1939–45 stance as we are in Ireland, except that where we write ‘Britain’ the Swedes write ‘Germany’. Guilt and shame are perhaps emotions all neutrals suffer.

Wartime neutrality is now regularly assessed with the luxury of hindsight in an ahistorical and often politicised manner. Current agendas are often placed on the decisions of over 70 years ago and these decisions are then repurposed to meet contemporary ends.

Neutrality remains almost unanimously acceptable as a foreign policy position for Ireland in 2013, yet it has been denounced as an immoral stance in World War II. During World War II, however, the moral belief of the Irish people was also almost unanimously in favour of neutrality. We are in danger of forgetting that the vast majority of the population of Ireland wanted the state to remain neutral during the war; neutrality was ‘the fundamental attitude of the entire people’, as one Irish diplomat put it in mid-1940.

As the memory of the Civil War fades, we also forget the real fear that joining the war on the Allied side would again split the country and probably lead to renewed civil strife. Was there in reality any alternative to neutrality that would have had wide popular acceptance? Neutrality was a flexible pragmatic foreign policy to get Ireland through World War II. Ireland did not wish to be dragged unwillingly into the war and would remain neutral until invaded. Neutrality was ‘the very essence of Irish independence’ and it would be defined to suit Ireland’s circumstances and needs.

Of particular significance in understanding the reasons for neutrality are a series of memoranda and papers drafted by Dr Michael Rynne, the legal adviser at the Department of External Affairs. Starting with ‘Ireland’s neutrality in practice’, written on 1 September 1939 and now the first document in DIFP VI, these papers set out the legal and philosophical basis of neutrality. In essence they are the nearest documents available to an intellectual corpus explaining wartime neutrality. In mid-September 1939 Rynne commented that ‘if we want to stay out of war, we must not tie ourselves to the strict law’; it was another expression of de Valera’s ‘certain consideration’ for Britain, which he expressed to German Minister to Ireland Edouard Hempel.

The resulting covert assistance to the Allies is often pounced upon to show how Ireland ‘wasn’t neutral really’. Irish diplomats and statesmen of 1939 to 1945 would not have agreed. To them Ireland might push the envelope of neutrality in favour of the Allies as the national interest and the progress of the war dictated, but Ireland remained a neutral, albeit from the Allied point of view a ‘benevolent neutral’.

Neutral Ireland actively defended its territory during wartime. The Defence Forces were not shy about taking the offensive if required. At least three belligerent aircraft were shot down by the Defence Forces, and anti-aircraft batteries regularly opened fire on suspicious intruders. After the North Strand bombing, Dublin protested emphatically to the German foreign ministry that ‘the strain’ caused by the raid ‘might well become insupportable’. Dublin had already informed Berlin that Luftwaffe air attacks on Irish cities could bring Ireland into the war on the Allied side.

The war came to Continental neutrals such as Denmark, Norway, the Netherlands, Belgium and Luxembourg when German forces rolled over their borders; Britain invaded non-belligerent Iceland. It is a twist of historical fate and a virtue of geography that Ireland managed to remain outside the destruction and death of the conflict. The nightmare scenario for Ireland was always invasion—from either side—or being drawn, against the national will, into a Great Power war.

There was no certainty that Ireland could hold out as a neutral, though survival became much easier through 1941 after Germany invaded the Soviet Union and the United States entered the war. Neutrality was a question of survival in a world where freedom of action was gravely limited. The morality of neutrality is in fact not the question. Neutrality was instead a question of pure national interest, the result of a cold assessment of Ireland’s power relationships and the possible outcomes of following strategies other than neutrality.

Should Ireland have done more to bend the parameters of neutrality? Documents in DIFP VII (1941–5), which is not yet on-line, show that Irish diplomats in Berlin, Paris and Rome did try, unsuccessfully, to intervene on behalf of Jews in Nazi concentration camps. It was a small effort but one about which there is little public awareness.

Were there alternatives to neutrality? What if de Valera had thrown Ireland in with the Allied cause in 1939? It would have been an undemocratic act, given public opinion, and was in any case constitutionally impossible without the assent of Dáil Éireann, except in the case of invasion, and such assent was unlikely to be obtained. Those who argue that Ireland should have joined the war in its final stages do not factor in the need to get the assent of the Dáil. Like other neutrals, Irish policy was that it would fight only after it was invaded.

‘Small nations like Ireland do not and cannot assume the role of defenders of just causes except their own’, wrote secretary of the Department of External Affairs Joseph Walshe in early 1941. Neutrality was a matter of how long Ireland could hold out and look after itself alone. It was about the present and, particularly during May and June 1940, about day-to-day survival when invasion and occupation by Germany or reoccupation by Britain seemed Ireland’s only future.

Small states suffer in the wars of great powers. We tend to forget that World War II began as a war between three great powers after one of them invaded Poland, not necessarily as a moral crusade against Nazi Germany. Why would Ireland join in a Great Power war?

Further, what would the consequences have been? The destruction of Irish cities in air raids and the death of tens of thousands of Irish men and women, both civilian and combatant, are the most obvious consequences. Perhaps we would judge this to be the price democracy must pay to preserve its existence, or perhaps we would judge it as being ultimately detrimental to Ireland, the bank guarantee scheme of its age? Perhaps the dividends of war via Marshall Aid would have been greater, and perhaps a post-war combatant Ireland would truly have taken part in the post-war boom?

This, of course, assumes an Allied victory, and rather naively Irish diplomats assumed that following an Allied victory or an Axis victory Ireland would continue to be master of its own destiny. Real planning for the post-war world began in Iveagh House only after 1943, when an ultimate Allied victory was likely. Ireland’s experience of the early Cold War nevertheless shows that, like today, Ireland could not isolate itself from the international system.

Readers may not like or agree with what DIFP VI says about Ireland and its international outlook during the war. Nonetheless, we should openly debate and be critical of, but not hand-wringingly ashamed of, our wartime history. We should judge Ireland’s World War II neutrality first and foremost in the context of its time, based on historical evidence and not on today’s contemporary agendas. HI

Michael Kennedy is the executive editor of the Royal Irish Academy’s Documents on Irish Foreign Policy series, volume IX of which will be published in 2014.

Documents on Irish Foreign Policy VI (1939–41) is available to read on-line free at www.difp.ie and in hard copy, published in 2008, from the Royal Irish Academy.