From the files of the DIB…‘A veritable tragedy of family likeness’

Published in 18th–19th - Century History, Issue 5 (Sep/Oct 2006), News, Volume 14

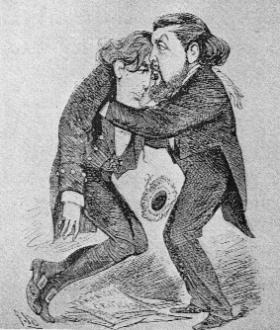

Willie consoling brother Oscar on the failure of his play Vera in 1883.

WILDE, William Charles Kingsbury (1852–99), journalist, was born 26 September 1852 in Dublin, eldest son of Sir William Wilde, surgeon and antiquary, and his wife, the poet and journalist ‘Speranza’ (Jane Francesca Elgee). He was educated at St Columba’s College, near Dublin, and Portora Royal School, Enniskillen, Co. Fermanagh, and was a good if erratic student, excelling at drawing and the piano. Towards the end of his schooling, however, he had already begun to be outshone by his younger brother Oscar and had to suffer his mother’s evaluation that ‘Willie is all right, he has a first-class brain, but Oscar will turn out something wonderful’. At Trinity College, Dublin, he took the gold medal in ethics, was a leading debater in the Philosophical Society, and had verse published before graduating BA (1873). He was called to the Irish bar on 22 April 1875 but never practised.

On his father’s death in 1876 he inherited the family house in Merrion Square, heavily mortgaged, and had to sell it three years later after failing to marry an heiress, despite his best efforts. In May 1879 he arrived with his mother in London and set up first in Grosvenor Square and then in 146 Oakley Street, where he presided over his mother’s salon and lived in the reflected glory of his brother. The brothers were markedly similar in appearance—both large and ponderous, with heavy-lidded eyes and sensuous lips. Neither was handsome, but until Willie’s advent Oscar had at least been original. He allegedly paid Willie to sport a moustache and beard to mitigate what Max Beerbohm called ‘a veritable tragedy of family likeness’.

Willie shared some other of his brother’s characteristics—he was excellent company and a good talker, though he tended to genial humour rather than dazzling wit. After contributing stories to the World and theatre criticism to Vanity Fair, he was taken on as a correspondent and leader-writer for the Daily Telegraph. He was inordinately lazy and liked to boast that he would arrive at the Telegraph offices at noon, come up with an idea for an article, then take a long lunch and a stroll in the park before repairing to his club to write up the article in an hour, after which he would remove for the night to the Café Royal. He showed uncommon energy in his coverage of the Parnell commission in 1888–9, however, attending the commission hearings with Oscar and writing impressive articles for the Daily Chronicle that counterbalanced the anti-Parnellite stance of The Times; but this turned out to be the high point of his career.

Two years later he finally succeeded in marrying an heiress and was able to stop ‘working’. He met the thrice-married Mrs Frank Leslie in summer 1891 (she was 55 to his 39), a former actress, an extremely wealthy newspaper publisher and an American celebrity. They were married in New York on 4 October 1891; the best man was the wit Marshall P. Wilder, so the magazine Town Topics joked that the groom was wild, the best man wilder, but the bride wildest. Willie omitted to follow Oscar’s advice to secure a pre-nuptial agreement, and so found himself divorced and destitute within two years. He had spent the marriage in New York’s Lotos Club, proclaiming that America needed a leisured class and entertaining members with parodies of his brother’s poems. The New York Times reported that he had been expelled from the Lotos for non-payment of debts, and summed him up as ‘Willie, known to fame as Oscar the Aesthete’s Brother, as Mrs Frank Leslie’s Ex-Husband, as having been “Born Tired” and as Chronically Willing to Drink all Night at Somebody Else’s Expense’.

On his return to London he found that rumours of his parodies had reached Oscar, who also suspected him of writing a negative review of his play Lady Windermere’s fan in the Daily Telegraph. The two were estranged and Oscar did not attend Willie’s second wedding in London in January 1894. When Oscar was imprisoned, however, Willie defended and supported him. Oscar wrote to W. B. Yeats that William ‘has been defending me all over London. My poor brother, he would compromise a steam engine’. When released on bail in May 1895, Oscar had to stay with Willie and suffer his moralising. In poor health, Willie lived off his wife and mother for his remaining years before dying in London on 13 March 1899.

He left one daughter, Dorothy Ierne Wilde (1895–1941), who greatly resembled her father and uncle. She divided her time between London and Paris, where she was, for a time, the toast of the salons, celebrated for her wit, intelligence and physical likeness to her uncle, as whom she used to dress up. She lived a ramshackle, bohemian life, carrying on affairs with men and women—she preferred the latter—and becoming a morphine addict. Her literary legacy was even less significant than her father’s: she survives only in a few witty letters and reminiscences, privately printed as In memory of Dorothy Ierne Wilde: Oscaria (1951). She died in London, a recluse, on 10 April 1941, just short of her 46th birthday, the age at which both her father and uncle died.

Bridget Hourican is an editorial assistant with the Dictionary of Irish Biography.