1825—THE APOCALYPSE IN IRELAND

Published in Features, Issue 1 (January/February 2023), Volume 31By Thomas P. Power

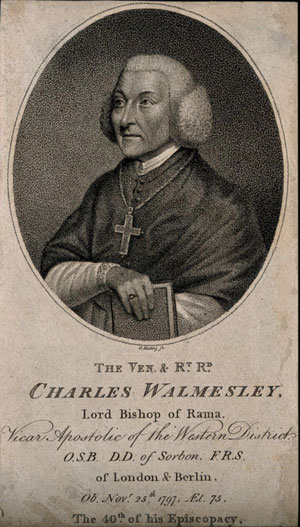

Above: Bishop Charles Walmesley (1722–97), a.k.a. ‘Pastorini’, author of A general history of the Christian Church (1771), which predicted the destruction of Protestantism in 1825.

Predictions about the end of the world became common in the wake of the French Revolution. In Ireland such predictions took different forms. Highly influential was a volume entitled in part A general history of the Christian Church, first published in 1771. Its author was an English Catholic bishop, Charles Walmesley (1722–97), writing under the pseudonym ‘Pastorini’. Based on the Book of Revelation (the last book of the New Testament), the General history contained a prophecy that was explosive for it predicted the destruction of Protestantism in 1825.

DISSEMINATION

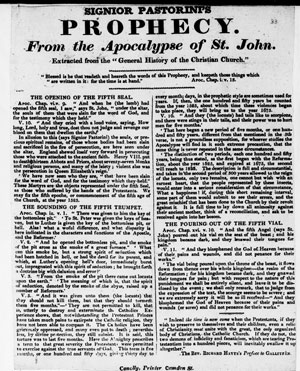

Multiple Irish editions and impressions of the General history appeared between 1790 and 1825 and circulated in the hundreds. While editions of the folio volume circulated among the reading élite, it was the broadsheet containing passages extracted from the larger General history that disseminated knowledge of the prophecy widely in Ireland. So famous did the broadsheet version of Pastorini become that it came to be known generically as a ‘Conolly’, after Robert Conolly of Dublin, who produced it in the thousands. What made it so appealing was that it was cheaper and more easily portable than the folio editions, which had hundreds of pages. It could be easily conveyed by hawkers, ballad-singers and peddlers for dissemination at fairs, markets and chapels.

The broadsheet could be read by its purchasers, or its contents could be communicated orally in schools by schoolmasters or around the country by ‘prophecy men’. Either way, knowledge of the prophecy was disseminated to the literate and illiterate alike and became the topic of regular conversation. In May 1824 George Warburton concluded that ‘I do not think there is an instance to be found amongst the lower class of people who do not speak of it in their common conversation, at their work, and on other occasions, when they are assembled together; they do not speak of it in any secret way, but as a thing known’.

What assisted dissemination was an improvement in biblical literacy in the early nineteenth century owing to the efforts of the different Bible societies and their ancillary educational organisations that were active in Ireland at this time, as well as initiatives of the Catholic Church itself. This allowed for an understanding of the text on which the prophecy was based and assisted in its adoption.

RECEPTION

Above: One of Robert Conolly’s broadsheets, containing passages extracted from the larger General history that disseminated knowledge of the prophecy widely in Ireland. (British Library)

The prophecy encountered a culture that believed in the presence of the supernatural in everyday life. Such belief embraced calendar customs and a variety of rituals designed to invoke supernatural powers to ensure the fertility of the land and animals and the good fortune of people generally. Whereas traditional folk religion was subject to the fickleness and unreliability of supernatural intervention, Pastorini provided certitude because it had a specific date that grounded its predictions.

The prophetic was also evident in poem and ballad, which could be absorbed into the expectations of the prophecy. Increasingly such genres referred to the heretical progeny of Luther and Calvin. ‘I am intoxicated by Luther’s breed’ and ‘the bloody breed of Calvin are holding the sway’ epitomised the desirability of their destruction. Moreover, traditional prophecies like those of Colmcille were proving inadequate and were replaced by the more radical prophecy of Pastorini, which provided the script for the end times and the timetable for its achievement. The credit given by Catholics to miracles in the summer of 1823—one involving the recovery of speech, the other recovery from paralysis—validated the potential for the prophecy to be fulfilled, serving to heighten expectations that the overthrow of Protestantism predicted by Pastorini was more than aspirational. The miracles received the approval of two bishops, one of whom saw them as providential for a renewed church and as a means of attracting Protestants back to the fold. All these elements aligned with the expectations of the prophecy.

THE ROCKITES

Though knowledge of the prophecy was widespread, it was particularly well known in Cork and Limerick, where rural unrest associated with the Rockites and Captain Rock arose in the early 1820s. What differentiated the Rockites from previous agrarian movements was the overt sectarian rhetoric used to justify their actions, and their use of Pastorini’s prophecy to give cohesion to the movement. Through this association, expectations that economic injustices would be righted, historic wrongs reversed, the Catholic Church restored and the land settlement overturned assumed prominence. Official sources made a specific connection between the spread of rural unrest, the occurrence of the Pastorini prophecy and declarations concerning the annihilation of Protestants. Expressions of sectarianism went beyond mere rhetoric, as Protestant churches were burned, Protestant clergy attacked and vulnerable communities targeted. When the Rockite threat subsided by mid-1824, adhesion to the prophecy remained and propelled itself forward in its own right without reference to the agrarian issues.

THE OMINOUS YEAR AND EMANCIPATION

The year 1825 arrived but the predicted destruction of Protestantism did not occur. The gap in expectations was filled by Daniel O’Connell and the Catholic Association. The Association gained greater popularity with the broadening of its membership to anyone who paid the 1d. per month, known as the ‘Catholic rent’. The rent showed its sharpest increase in the latter months of 1824 and into early 1825, coinciding with expectations as regards prophecy fulfilment. In the initial stages of collection, priests were non-committal as to the use to which the rent was to be put. This only led to speculation among contributors that it was intended to support the achievement of the prophecy.

It was in the transition period between December 1824 and January 1825, when expectations were heightened, that O’Connell’s status changed to one where he became associated with the achievement of the prophecy. O’Connell replaced Captain Rock as the focus of expectations, thereby assuming a messianic role. His transformation was enhanced in the spring of 1825 when, at a time when the Catholic cause was at a low point, O’Connell proposed a redating of the prophecy. Originally Pastorini had calculated that the destruction of Protestantism would occur 300 years after 1525. Now O’Connell claimed that this was a misprint and that the correct date was 1528, the beginning point from which the 300 years should be calculated and at the conclusion of which, i.e. April 1829, the demise of Protestantism would occur. The details of O’Connell’s redating were widely reported in the Dublin and Belfast press.

Making 1828–9 rather than 1825 the ominous year when Protestantism would expire accorded well with O’Connell’s campaign for Catholic Emancipation and implicitly assisted in its achievement. As matters transpired, the redated prediction was close enough, for the Catholic Relief Act received royal assent on 13 April 1829, thus lending retrospective legitimacy to O’Connell’s prediction and raising his stature further.

CATHOLIC RESPONSES

Leading Catholic bishops were familiar with the contents of the prophecy and some of them condemned it publicly. They sought to assume control and to direct apocalyptic expectations through the diversion of popular adherence to the prophecy and by highlighting the difficulty of interpreting Revelation. In reality, however, because of class differences in Catholic society, episcopal condemnations were ineffective in deterring rural agitators from their embrace of the prophecy. The same was true of Catholic priests, who, though they condemned the rural violence and questioned the veracity of Pastorini, found that acceptance of their declarations was not automatic. To some degree, priests themselves may have been ambivalent, given the less deferential calibre of priest emerging from Maynooth. Middle- and upper-class Catholics dismissed the prophecy and its claims. At a time when they were seeking additional relief, they were anxious to downplay the prophecy’s currency among the lower class. Such divisions in Catholic society disappeared once 1825 dawned and all classes united around the emancipation cause.

PROTESTANT RESPONSES

Fearful that events in France would be repeated in Ireland, apocalyptic fervour among Irish Protestants grew sharply in the 1790s. This was increased when Pastorini’s prophecy predicted their destruction in 1825. The prospect of their elimination elicited memories of 1641, 1798 and 1803.

Protestants had a perception that Catholic priests were promoting not just Pastorini but also anti-Protestant literature. There was also a concern that the miracles of 1823 were to be used by Catholic priests to strengthen the position of the Catholic Church and as a means of inducing Protestants to convert, a process encouraged by the prophecy. They discerned a clear connection between the miracles and wider Catholic claims to precedence in Ireland.

To contribute to the reduction of Protestant fears, Protestant writers challenged the accuracy of the prophecy’s claims. Based on a rigorous sifting of the relevant passages in Revelation, the predictions drawn by Walmesley were shown to be defective. To allay Protestant anxieties, one author demonstrated that the calculation of 300 years from the beginning of the Reformation should be based not on 1525 but on the more conventional year of 1517, when Martin Luther posted the Ninety-Five Theses. That would make the prediction of Protestant destruction datable to 1817, when nothing transpired. Hence any prediction as regards 1825 was erroneous and any fears unwarranted.

The charge that Orangemen were responsible for disseminating Pastorini’s prophecy was an additional cause of anxiety for Protestants. The Catholic Association wanted to assign some culpability for the prophecy to Orangemen, a charge articulated most intensely in 1825, when the Association’s prospects and O’Connell’s reputation were at a low ebb.

While nothing came of the specific predictions of annihilation to the degree anticipated, Protestants feared that something apocalyptic was in the air and that their position was no longer secure. The overriding, cumulative sense was of an apocalyptic portent, particularly after the achievement of Catholic Emancipation in 1829. In effect, emancipation was for Protestants the refracted realisation of Pastorini’s prophecy. While some reports may appear alarmist, nevertheless the perception of a threat to their safety was sufficient to cause Protestants to emigrate in large numbers.

EXODUS

Emigration from Ireland in the post-1815, pre-Famine period is characterised by its British North American orientation and its largely Protestant composition. Multiple data sets indicate that most migrants from Britain and Ireland to British North America were Irish. For instance, the evidence from passenger lists for ports in Britain and Ireland for 1825–30 indicates destinations in the USA (80,522), Australia (64,170) and British North America (90,172). Of this total of 177,111, emigrants from Ireland made up 80,979 or about half the total. They comprised two thirds (60,204) of those who went to British North America (90,172).

The distinctly Protestant character of this emigration is attested to by newspaper reports, one from Waterford in 1826 stating:

‘Where emigration has taken place from certain districts it was largely made up by the emigration of Protestants; and from universal, concurrent testimony, we apprehend there can be no doubt generally that the disposition to quit the country exists more strongly among Protestants than among Roman Catholics.

It was recalled in 1868 that the emigration of Irish Protestants in the period 1825–34 numbered 175,000, which would be an annual average of 17,500. It was estimated in 1832 that 60,000 Protestants had emigrated since 1829, the year of emancipation, which would mean an annual average of 15,000. Emigrants consisted of farmers, artisans, shopkeepers, tradesmen and professionals. One source in 1833 suggested that the exodus was not confined to those of landed status, as ‘the whole body is in motion—the great body of Protestant farmers, and mechanics, and manufacturers are in motion’. People of means chose to emigrate increasingly because of the sectarian atmosphere in Ireland.

NEW JERUSALEM

The opportunity to emigrate to British North America (or Canada as it became) appealed because the language of administration, politics and the law was English. There was a demand for farmers and an educated élite for the colony to succeed economically and administratively, and Ireland filled the need. In the New World the denominational imbalance was reversed, putting Protestants in a majority. The threat from Catholics in the Old World was reversed in the New.

Early Irish Catholic settlers were loyal subjects of the British Crown, its clerical leaders disavowing support for O’Connell. In contrast to Catholic settlements, Protestant communities in Canada quickly became organised and viable. The Orange Order was transplanted to Canada, where it provided cohesion, solidarity and opportunity as part of the settlement process. A distinct form of churchmanship—low church, evangelical—was contributed by the Irish to the emergent colonial church. In succeeding decades hundreds of new churches were erected. Because of the heightened sectarianism of Ireland in the 1820s, sectarian prejudices were also exported. Unsurprisingly, the cumulative set of circumstances around Pastorini nurtured an anti-Catholic bias among Protestant emigrants, epitomised in yearly riots in Toronto on 17 March and 12 July.

Ultimately, the aims of the prophecy were achieved, though not to the degree advocated. The Catholic Church triumphed and Protestantism was reduced; Protestants emigrated in large numbers; although there was not a complete overthrow of the land settlement, the Protestant middle interest was decimated; and though there was not a massive influx of Protestants into the Catholic Church, the number of conversions was considerable. Irish democratic nationalism, drawing as it did on French revolutionary fervour, stimulated by the idealism of the United Irishmen, in reaction to Ascendancy excesses and culminating in the achievement of Catholic Emancipation in 1829, contained within itself a sharp sectarian edge that it had acquired in large part because of Pastorini’s prophecy.

Thomas P. Power is sessional lecturer in the History of Christianity, Wycliffe College, University of Toronto.

Further reading

J.S. Donnelly, Captain Rock: the Irish agrarian rebellion of 1821–1824 (Madison, 2009).

T.P. Power, The Apocalypse in Ireland: prophecy and politics in the 1820s (Oxford, 2023).