NARRATIVE: 1169 and all that

Published in Features, Issue 3 (May/June 2019), Volume 27Since history is written by the victors, it is not surprising that our most detailed narratives of the invasion of Ireland that began in 1169 are partisan contemporary accounts by the likes of Gerald of Wales. Can we know what actually happened?

By Seán Duffy

In the late 1160s Ireland was invaded and—for the first time in its recorded history—conquered. Yes, the first invaders were invited to get involved by an Irish king and, yes, there were undoubtedly those—allies of that same Irish ruler—who must initially have made them welcome. Nevertheless, the recruitment of what had seemed comrades-in-arms rapidly spiralled into a full-fledged invasion intent upon the conquest of Irish land, and within four years England’s king was claiming Ireland as his own.

Anglo-Norman interest in Ireland

In a sense it could be said that Ireland’s future was up for grabs from the moment that Duke William of Normandy overthrew the Anglo-Saxon regime and conquered England in 1066. William certainly pushed his weight around in Scotland and Wales and it is said that he was toying with the idea of an Irish conquest at the time of his death in 1087, but nothing happened straight away. It was following the succession to the English throne in 1154 of that most imperial of the Conqueror’s heirs, his great-grandson Henry of Anjou (creator of the short-lived ‘Angevin Empire’), that the prospect of intervention in Ireland reappeared. One of Henry II’s first royal councils, held at Winchester in September 1155, was called for the specific purpose of organising a conquest of Ireland, over which his brother William would be made king.

The idea of an Irish invasion was postponed, however, on the advice of their mother, the Empress Matilda. Incidentally, she was so called because before her marriage to Geoffrey Plantagenet of Anjou she had married the German King Henry V, who became Holy Roman Emperor. It is noticeable that contemporaries (including the Irish) regularly referred to her son Henry, the conqueror of Ireland, as Henry FitzEmpress, as if to emphasise this imperial association.

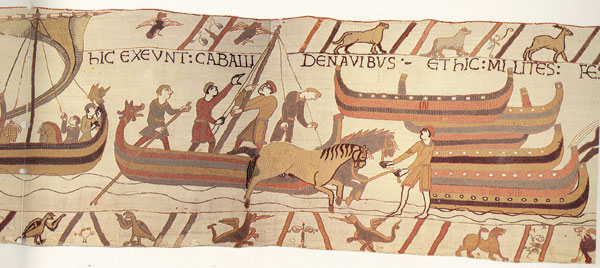

Above: Detail from the Bayeux Tapestry, depicting the Norman conquest of England in 1066. Ireland’s future was up for grabs from the moment that Duke William of Normandy overthrew the Anglo-Saxon regime and conquered England. (Musée de la Tapisserie de Bayeux)

Laudabiliter

It may be that the initiative for an Irish conquest emanated from Canterbury, whose archbishops since the Norman conquest of England had sought to exercise jurisdiction not just over all England but also over the whole archipelago, including Ireland. Such a role was, however, cut short in 1152, when the papacy ratified a reorganisation of the Irish church that made no provision for Canterbury’s continued involvement. It can hardly be a coincidence that when the English cardinal Nicholas Breakspear was installed as Pope Adrian IV in 1154—within weeks of Henry II’s accession—the archbishop of Canterbury sent his secretary on a mission to Rome. This man, the great English scholar John of Salisbury, was a friend of the new pope and obtained a papal privilege known as Laudabiliter, authorising Henry II to invade Ireland, ostensibly to reform the Irish church.

The contemporary belief was that all islands belonged to the Holy See, according to the so-called Donation of Constantine, and that therefore the English pope was within his rights in granting Ireland away to the English king. We now know, however, that the Donation of Constantine was a forgery and no such right existed. It is also possibly the case that the text that has come down to us of Laudabiliter, the papal grant of Ireland to Henry II, is also a forgery, or at least heavily redacted: it seems to originate in the history of the conquest written by Gerald of Wales, who was in effect a paid propagandist for the conquerors and closely related to some of the most important early leaders of the invasion. In a sense, though, it does not matter whether we have the correct text of Laudabiliter; Pope Adrian probably did issue his approval for an Irish expedition by Henry II, and contemporaries (including the Irish) did not doubt that English actions in Ireland had the support of the Holy See.

Above: Mac Murchada struck a deal with one of Henry’s least favourite subjects, Richard fitz Gilbert de Clare, nicknamed Strongbow (left): the latter would come to Ireland to secure Diarmait’s restoration, marry his daughter Aífe (right) and inherit Mac Murchada’s claim to the overkingdom of Leinster—detail from the watercolour version of McLise’s The Marriage of Strongbow and Aoife. (National Gallery of Ireland)

Mac Murchada’s expulsion

Henry II, however, did nothing for a number of years. Instead, he channelled his ambition into expanding his vast domains elsewhere. In 1165 he led a military expedition against the Welsh. While he himself led the land army into Wales from the east, he recruited the assistance of the fleets of Dublin and other Irish port towns to attack the Welsh from the west. Since the king of Leinster, Diarmait Mac Murchada, was overlord of Dublin and Wexford, this surely put King Henry into contact with him and might explain why Mac Murchada soon afterwards turned to King Henry for assistance.

Diarmait Mac Murchada was king of Uí Chennselaig (County Wexford and part of Carlow) and claimed to be overking of all Leinster, but he struggled to command the loyalty of the other kings of the province and of the Hiberno-Norse of Dublin, and in 1166 they rebelled against him. They joined forces with the new high-king of Ireland, who was the king of Connacht, Ruaidrí Ó Conchobair, and his ally Tigernán Ó Ruairc of Bréifne. The latter in particular was a long-standing foe of Mac Murchada’s: they were political rivals who both wanted to extend their rule into Mide (counties Meath and Westmeath) and they were personal rivals since Mac Murchada had scandalised opinion by absconding with Ó Ruairc’s wife Derbforgaill a decade earlier. When all Diarmait’s enemies ganged up on him in 1166, he astonished everyone by fleeing overseas.

We have two accounts of the momentous events that followed: the Latin narrative by Gerald of Wales, Expugnatio Hibernica (‘The Conquest of Ireland’), written about twenty years later, and the poem in French usually called ‘The Song of Dermot and the Earl’, written about the same time, which may be an independent witness. According to both, Mac Murchada made straight for Bristol. He was no doubt familiar with it from its trading links with Wexford and Dublin, but Bristol also had strong associations with Henry II since his youth. The town’s leading mercantile oligarch, Robert fitz Harding, offered asylum to the Irish king and his family and pointed him in the direction of King Henry, who was then on the Continent. Diarmait crossed the Channel to meet him, explained his plight and sought assistance. More importantly, he swore an oath of fealty, accepting Henry II, the king of England, as his feudal lord. In return, King Henry gave him a promise of help—as Diarmait was entitled to expect from his new lord—along with letters permitting Henry’s subjects to go to Ireland to his aid. Mac Murchada returned to Bristol, eventually striking a deal with one of Henry’s least favourite subjects, the lord of Strigoil (Chepstow), Richard fitz Gilbert de Clare, nicknamed Strongbow: the latter would come to Ireland to secure Diarmait’s restoration, marry his daughter and inherit Mac Murchada’s claim to the overkingdom of Leinster.

Mac Murchada’s return

Diarmait then travelled to south Wales, whose king, Rhys ap Gruffudd, facilitated him in obtaining further offers of support from two half-brothers, sons of the Welsh princess Nest. One was Robert, son of Stephen of Cardigan, who was released from prison by Rhys on condition that he go to Ireland, and the other was Maurice, son of Gerald of Windsor, both of whom would go on to play major roles in the conquest (Maurice being founder of the great Geraldine dynasty). Diarmait returned to Ireland about August 1167, but only with some men from the Flemish colony earlier established in Pembrokeshire by Henry I, led by members of the fitz Godebert family (they settled in Ireland, adopting the surname Roche). After his initial reoccupation of his dynastic territory of Uí Chennselaig in south Leinster, the army of the high-king, Ruaidrí Ó Conchobair, came against him and two minor battles ensued, among those slain being ‘the son of the king of Wales’, presumably Rhys ap Gruffudd’s son; in the end, Diarmait was allowed possession of part of his core lands and handed over hostages to the high-king as a sign of his good faith.

Above: Long after Gerald of Wales, the claim that Irish rulers freely submitted to Henry II was included in proclamations of the English right to rule Ireland. In the late 1780s Vincenzo Waldré produced this painting of the Irish princes’ submission for the ceiling of St Patrick’s Hall in Dublin Castle. (National Monuments Service)

The 1169 landings at Bannow

Mac Murchada’s ambitions remained alive, however. He sent letters to Wales urging on those Cambro-Normans who had previously offered support, and finally about 1 May 1169 the first contingent arrived at Bannow Bay, Co. Wexford, in three ships under Robert fitz Stephen. The dozen knights included an illegitimate grandson of King Henry I (Meiler fitz Henry), the older brother of Gerald of Wales (Robert de Barry), a son of the bishop of St Davids (Miles fitz David fitz Gerald) and an uncle of Strongbow’s (Hervey de Montmorency), bringing 60 men in mail and 300 foot-archers ‘of the elect of the youth of Wales’; they were joined the next day by two ships under another Fleming from Haverfordwest, Maurice de Prendergast, with a further ten men-at-arms and some archers. Although small in number, the invading Anglo-Norman forces were well armed and well organised, providing immediate military superiority over the Irish, who, however fearless, were disorganised by comparison, lacking armour and sophisticated weaponry.

Having rendezvoused with Mac Murchada, they marched on Wexford, which they took in a two-day assault, the town being conferred on Robert fitz Stephen and Maurice fitz Gerald, and the two adjoining cantreds (later baronies) of Bargy and Shelburne being granted to de Montmorency. Mac Murchada now set his sights on Osraige (Ossory), a buffer kingdom between Leinster and Munster, and he also campaigned to secure the submission of the rebellious lords of north Leinster. King Ruaidrí Ó Conchobair marched against Mac Murchada but, badly underestimating the situation, agreed to his staying in power in Leinster in return for Diarmait’s giving his son as a hostage and secretly promising to send back his foreign troops when all Leinster had been re-secured.

Strongbow’s arrival

Instead, the invasion stepped up a gear in 1170 when forces under another Geraldine, Raymond ‘le Gros’, son of Maurice fitz Gerald’s older brother, William, landed at Baginbun near Hook Head. Here they defeated an assault by the Hiberno-Norse of Waterford, 70 of whom were captured, mutilated and thrown from a cliff—hence the saying ‘At the creek of Baginbun, Ireland was lost and won’. In August, despite the arrival of messengers from Henry II forbidding it, Strongbow sailed from Milford Haven to Crook (Passage East), near Waterford. His landing was followed by a bloody but successful assault on Waterford itself. What is important about this is not just that Waterford was, after Dublin, the largest of Ireland’s towns. It is that these men came to Ireland allegedly to help restore Mac Murchada to the kingship of Leinster, but Waterford is in east Munster, outside Mac Murchada’s kingdom, indicating that they had other goals.

At Waterford Strongbow married Diarmait’s daughter, Aífe, and it is clear that he was now the inheritor of Mac Murchada’s ambitions beyond his core patrimony. Technically speaking, since Irish kingship did not descend in the female line, Strongbow had no right to succeed Mac Murchada as king of Leinster when the latter died in May 1171, but such considerations mattered little now.

Inevitably, Strongbow set his sights on Dublin, the country’s richest asset and probably the only Irish location well known abroad. Its conquest was therefore widely reported in contemporary chronicles when it happened in September 1170, apparently by a surprise assault during surrender negotiations that saw a slaughter of the inhabitants and the flight overseas of its Hiberno-Norse king, Ascall Mac Turcaill. The latter returned from the Western Isles in 1171 and attempted to retake the city, but his naval forces were massacred and he was beheaded. Ruaidrí Ó Conchobair also undertook a lengthy siege of the walled city, which likewise ended ignominiously when the besiegers were caught unawares by a sortie of the new English garrison.

Henry II’s expedition

Henry II responded to news of Dublin’s fall by calling the adventurers home and imposing a blockade. Only in the autumn of 1171, when Henry was preparing to go to Ireland himself, did Strongbow come to him on the Welsh border and make his peace. Henry proceeded to south Wales and, with a fleet of 400 ships, on 17 October 1171 became the first reigning king of England to set foot on Irish soil when he landed at Crook. Strongbow did homage to him for Leinster, which was confirmed to him (excluding Dublin and its hinterland and the other pre-existing towns) for the service of 100 knights.

At least two Irish province-kings, Ó Briain of Thomond (north Munster) and Mac Carthaig of Desmond (south Munster), also submitted to Henry, no doubt hoping that he would protect them from the aggression of his barons. Church leaders likewise publicly approved of Henry’s intervention and swore fealty to him, sending letters to Pope Alexander III acknowledging Henry’s lordship (to which the pope responded, encouraging further church reform); under Henry’s auspices the Council of Cashel was held, which ordained that the Irish church would henceforth be run along the lines of that of England.

Henry arrived in Dublin on 11 November 1171, and there at Christmas, in a specially built post-and-wattle palace on the site of the Viking Thingmoot (in what is now Dame Street), he held a Christmas feast to which many more Irish kings and lords came and submitted. The high-king, Ruaidrí Ó Conchobair, refused to submit to Henry, however, as did the kings of north-west Ulster. While at Dublin, Henry issued a charter granting the city to the men of Bristol—no doubt a reward for past loyalty and for their logistical role in the organisation of his Irish expedition—and its merchants were urged to inhabit Dublin, where they would enjoy the same liberties they held throughout Henry’s lands.

After nearly four months in Dublin, about 1 March 1172 Henry went to Wexford, where he granted the kingdom of Mide from the Shannon to the Irish Sea to the Herefordshire baron Hugh de Lacy for the service of 50 knights. Mide had recently been sliced up between Ó Conchobair and Tigernán Ó Ruairc, who were at best ambivalent to Henry’s new regime, and it was presumably taken to punish them and also to protect Dublin, the headquarters of the new colony, which was given into de Lacy’s custody. Remaining at Wexford until 17 April, Henry then sailed to Wales, having conquered Ireland without unsheathing a sword.

From conquest to colonisation

Above: ‘Hugh Lacey Baron of Ewias Lacy in England & of Meade in Ireland’, from a sixteenth-century genealogy of Elizabeth I. On 1 March 1172 Henry granted de Lacy the kingdom of Mide. (British Library)

A nominal conquest achieved, the business of converting it into reality began. Garrisons were installed in Dublin, Waterford and Wexford, and immigrants were arriving in force from English and Welsh towns. Dublin’s hinterland was now a royal shire and here a new English landholding class was installed, manors were established for the exploitation of this newly won land and tenants attracted across the Irish Sea by making the labour services lighter than in contemporary England. A similar process of what is called subinfeudation happened in Leinster and Meath under Strongbow and de Lacy: these ancient provinces were carved up and granted to knightly tenants of their choosing, who in turn constructed castles at strategic locations, founded new boroughs and established their own subtenants on lands seized from their original Irish lords, which they set about repopulating with predominantly English colonists (although many Irish peasant communities no doubt remained in situ).

Disenchantment rapidly set in among the Irish kings when the impact of militarily enforced colonisation hit home. The settlers in Leinster were now pushing westwards into Munster, and Irish resistance became widespread. King Ruaidrí Ó Conchobair led several interprovincial armies against the new settlements and, although divisions prevented united opposition and success was largely confined to the razing of castles, both sides began negotiations that culminated in the Treaty of Windsor, agreed in October 1175. This acknowledged Ruaidrí’s position as king of Ireland in everything but name, under Henry, who would be paid an annual tribute in cowhides, collectable from all Ireland except the parts now in English hands.

The treaty was viewed by Ruaidrí’s side as a major achievement which might have seen the survival of Ireland as a distinct kingdom only loosely subordinate to England, but the new colonists in Ireland no doubt resented the compromise for this very reason. The Treaty was therefore soon breached, most dramatically by John de Courcy’s spectacular conquest of the kingdom of Ulaid (east Ulster), beginning in February 1177. Within months Henry had abandoned any pretence of abiding by the Treaty of Windsor, and at the Council of Oxford later that year he granted away two more Irish provinces—Thomond and Desmond—to others of his barons, and appointed his own ten-year-old son John as lord of Ireland. It would be another eight years before the latter visited Ireland, in 1185, by which time accommodation with the Irish had been abandoned and an all-out conquest was under way.

Seán Duffy is Professor of Medieval Irish and Insular History at Trinity College Dublin.

FURTHER READING

A. Cosgrove (ed.), A New History of Ireland II: medieval Ireland (Oxford, 1987).

S. Duffy, Ireland in the Middle Ages (London, 1995).

M.T. Flanagan, Irish society, Anglo–Norman settlers, Angevin kingship (Oxford, 1989).

G.H. Orpen, Ireland under the Normans, 1169–1333 (reprint: Dublin, 2005).