Col. James Fitzmaurice—Ireland’s greatest aviator

Published in 20th-century / Contemporary History, Features, Issue 2 (March/April 2019), Volume 27The Irishman who made the first successful east–west flight across the Atlantic in April 1928.

By Teddy Fennelly

The First World War hastened the advancement of aircraft technology. From its use as an experimental armament of war in 1914, its enhanced mobility, stability and speed had established the airplane as an essential weapon of warfare by the time hostilities ceased in 1918. When peace was restored, aviators and aviation companies could set their sights on vastly more ambitious projects than had been harboured by pioneers in 1914.

In the post-war years there was a worldwide public fascination with aviation and with breaking new barriers in speed, distance and endurance. Transoceanic flight was now seen as an achievable ambition, and flying the North Atlantic was seen as the ultimate test.

Alcock and Brown, and Lindbergh

This was soon accomplished when two British airmen, Capt. John Alcock (pilot) and Lt. Arthur Whitten Brown (navigator), made the first non-stop transatlantic flight in June 1919. Their Vickers-Vimy biplane took off from St John’s, Newfoundland, and crash-landed near Clifden, Co. Galway, almost sixteen and a half hours later. But it was the all-American hero Charles Lindbergh who, by flying solo from New York to Paris in 1927, proved that flying the ocean from the American side was well within the scope of human endeavour.

Attempting the crossing from the European side with the aircraft and technology then available was a very different proposition, however, and was considered impossible by the aviation pioneers of the day, including Lindbergh himself. The most obvious difference was that the prevailing winds backed flights from the west, but other factors came into play as well. The European coast is more densely populated, runs due north and south and was better charted than the unwelcoming North American coastline, running sharply south-west from Newfoundland. There was also the problem of the erratic magnetic variations known to confuse compass readings in the area of the Great Banks off Newfoundland, near American landfall.

The North Atlantic would not be finally conquered until it was flown in both directions, and there was lasting fame and prestige to be won by the first country and the first aviators to fly it in the more difficult direction. But as the number of tragedies grew, particularly some high-profile ones in transatlantic east–west attempts, public opinion forced governments to frown on any further transoceanic adventures.

Comdt James Fitzmaurice

From his base at Baldonnel aerodrome, the officer-in-command of the Irish Air Corps, Comdt James Fitzmaurice, remained undaunted and dreamed of being the first to achieve the ‘impossible’ goal. He had earned his wings with the RAF as the First World War ended, and had gained valuable experience, especially in night flying, through his involvement in experimental post-war mail flights between England and Germany. He had his sights set on putting the infant Irish Free State on the world stage in aviation.

At first Fitzmaurice tried to organise an all-Irish attempt. He eyed up a Martinsyde Type A Mark 1, the first aircraft purchased by the Air Corps, as a suitable machine. This was later christened The Big Fella because of its connection with Michael Collins; it had been put on secret stand-by in London to whisk Collins home in the event of the Anglo-Irish talks collapsing in 1921. Fitzmaurice’s request got short shrift from the government.

He soon became frustrated in his efforts to organise an all-Irish attempt because of the refusal of the Free State authorities to back the project. An opportunity came when on 16 September 1927 he teamed up with the British pilot Capt. R.H. McIntosh, known as ‘All-Weather Mac’ because of his vast experience in flying in all kinds of weather conditions, for a transatlantic attempt in the Princess Xenia, a Fokker F.7A monoplane. Five hundred miles out into the Atlantic, in the midst of a violent storm, they knew the game was up and turned back, landing safely on a beach in County Kerry. Turning back was not an easy option for two fearless aviation pioneers, but they realised that to persevere meant certain death. To escape with their lives meant a chance to live and fight another day.

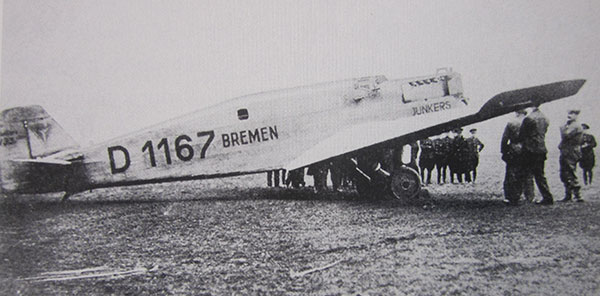

Fitzmaurice was more determined than ever to fulfil his dream. In early 1928 he was invited to join two Germans, Capt. Hermann Koehl, a decorated First World War bomber pilot, and his aristocratic Prussian friend and sponsor, Baron von Huenefeld, as co-pilot and navigator, on a second attempt in the Bremen, a Junkers W33 single-engine monoplane. Like the Irishman, the two Germans had been involved in a failed transatlantic attempt in the previous year. Because all such risky long-distance flights were now banned in Germany, they decided to make their attempt from Ireland instead.

Dangerously overloaded with fuel

President W.T. Cosgrave (along with his son Liam, later to become taoiseach) and other members of the government were among a big crowd who turned out at Baldonnel in the early morning of Thursday 12 April to cheer them on their way, with New York as their destination.

The Bremen was dangerously overloaded with fuel for the long journey. To make room for more fuel the airmen brought with them a bare minimum of personal requirements, even to the extent of insisting on having their oranges peeled beforehand to reduce weight. The take-off, along an extended and bumpy runway, was a dangerous exercise in view of the lethal cargo aboard. There was immediate drama when a sheep wandered across the path of the plane as it gathered speed for take-off. The Bremen barely managed to get airborne before running out of runway, and it skimmed the perimeter hedges and trees as it sluggishly rose higher and higher.

Once safely airborne, the Bremen made steady progress across the Atlantic as the hours of daylight passed, but as darkness fell it found itself in the eye of a violent storm. Koehl and Fitzmaurice alternated on the controls. Then the lights went out. Fitzmaurice flashed around his torch to locate his charts in the confined cockpit, which was semi-open to the elements, when he discovered oil covering the cabin floor. He could not find the leak but he was more than a little worried when he discovered that the oil gauge on the main oil tank was registering near to empty. Voices could not be heard above the noise of the engine and Fitzmaurice passed on the alarming message in a note to Koehl. The captain was shocked and said a silent prayer. Fortunately, however, it turned out to be a false alarm.

It was an endless night as the plane inched forward over a raging ocean, impatiently awaiting its next victims. Their compasses and other instruments were giving confusing readings and they had no radio. The storm forced them hundreds of miles off course to the north, and when the aviators got sight of a clear sky again they reset their course southwards. When daylight broke the airmen could see a vast snowy wasteland below. It was a forbidding scene but they were absolutely elated. They knew that it must be American soil. They also knew that their fuel was running low and that they had to find a suitable landing ground soon. Almost overcome by exhaustion, they managed to struggle on, hour after hour.

Landed at Greenly Island, Quebec

Then, through the swirling clouds, Fitz spotted what at first seemed the funnel of an ocean liner. On closer inspection he could see that it was a lighthouse, and there was a possible landing area nearby. Capt. Koehl nodded confirmation and, after 36½ hours in the air, he brought down his trusty Bremen safely on what was an iced-over reservoir on Greenly Island, a remote and snowy wilderness, situated between Newfoundland and the Canadian province of Quebec, from where the aviators were eventually rescued. A famous American airman, Floyd Bennett, died in the rescue attempt. Charles Lindbergh made a heroic flight of mercy with the serum sought urgently by Bennett’s doctors, but it arrived too late to save his friend’s life. It was Friday 13th—what a day to tempt fate!

The Atlantic had at last been conquered by air. One of the most significant milestones in aviation history had been achieved. News of the flight of the Bremen was flashed around the world. In America it was headlined as the greatest story of the century. Efforts to rescue the airmen and the Bremen kept the story in the headlines for weeks. The New York Times headlined the story for nineteen out of 21 days.

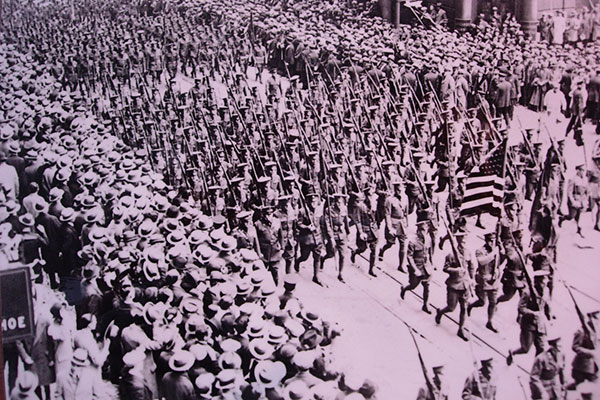

Reception in New York bigger than Lindbergh’s

The reception in New York was bigger than the one given to Lindbergh. Over two million people lined the ten-mile route and more than 10,000 soldiers from crack US Army and Navy regiments marched. There were similar unprecedented scenes of wild acclaim awaiting the aviators in Soldier Field, Chicago, and in the other big cities they visited in the USA and Canada.

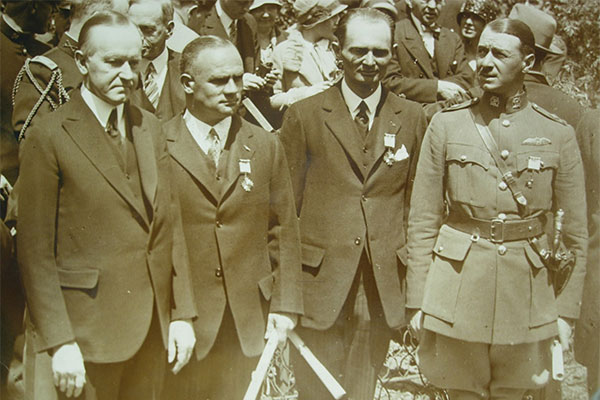

The aviators were presented with Distinguished Flying Crosses by President Calvin Coolidge—the first non-Americans to receive the honour. Henry Ford, the motor manufacturer, entertained them in Detroit. They sold the rights of their book, The Three Musketeers of the air, to a publisher.

The welcome back in Europe was even more ecstatic. The airmen were honoured wherever they went in Germany. Fitzmaurice and his German comrades received the Freedom of the City of Dublin and were entertained at a lavish state reception. He had put Ireland on the international aviation map.

Fitzmaurice, soon to be promoted to colonel, carried with him his country’s tricolour flag and a letter of greeting from W.T. Cosgrave to President Coolidge, and he wore his Irish Army uniform on the flight and at all the receptions thereafter. He was the dashing young hero of the hour, and by projecting his country to the fore in the glamorous world of aviation he presented the best possible image of the new Ireland. At a time when the infant Irish Free State was struggling to win recognition as an independent entity, he put his life on the line for his country and earned for it an unprecedented amount of publicity, respect and goodwill.

Teddy Fennelly is president of the Laois Heritage Society.

FURTHER READING

T. Fennelly, Fitz and the famous flight (Portlaoise, 1998).

W. Hotson, The Bremen (Toronto, 1988).