Sectarianism spills over? The St Johnston riot of 1972

Published in 20th-century / Contemporary History, Features, Issue 6 (November/December 2016), Volume 24WHAT WAS THE CONTEXT OF THE 12 JULY RIOT IN ST JOHNSTON, CO. DONEGAL, DURING WHICH 70 PEOPLE WERE INJURED AND PROTESTANT CHURCHES, BUSINESSES AND HOMES ATTACKED?

By Brian Hanley

July 1972 was the worst month of the bloodiest year of the Northern Ireland conflict. As violence intensified, many in the Republic feared that the ‘Troubles’ were spilling over into the South. July also saw, in St Johnston, Co. Donegal, the most serious incident of large-scale sectarian disorder in southern Ireland since the 1930s. The trouble started when local Orangemen returned from the parade at Garvagh and formed up at the railway station to march the 400 yards to their hall. They were attacked on the way by a large crowd, who had gathered outside a pub. Missiles were thrown and Orange banners were broken and torn. While calm was temporarily restored, clashes erupted again later that night. The Masonic hall was burned down, an attempt was made to set fire to the Orange hall, petrol bombs were thrown at the Presbyterian church hall, all the windows in the Congregational church were broken and a Protestant-owned store was gutted by fire. Several Protestant homes had their windows broken, and in one case an attempt was made to break into a house. Three men, accused of trying to force their way into a Protestant home, were wounded by a shotgun blast fired by the householder. A Garda squad car was overturned and set on fire; stones were thrown at firemen and one of their engines hijacked. Eventually troops had to be called in to assist Gardaí in quelling the disturbance. The Irish Independent reported that ‘one Protestant woman said yesterday that local Catholics went berserk. She said they smashed their way into her home after attacking her car. She alleged they also attacked the home of a 77-year-old pensioner.’ The same report stated, however, that ‘local Catholics claimed the Orangemen started the trouble by marching through the village’. Despite an uneasy calm being restored, there were reports that several Protestant families had fled to relatives in Derry.

In the aftermath of the violence, a local barrister explained that the religious make-up of the village was ‘roughly 50–50’ and that relationships between the two communities had been good in the past. The nationalist Derry Journal condemned the rioting, asserting that the Orangemen had a ‘perfect right to their parade’ in ‘their native village’. The Provisional IRA in Donegal also stated that the rioting ‘had nothing to do with them, and that in fact they deplored it’, and offered to provide protection for Protestants. Local republican Frank Morris described ‘Orange marching [as] a great tradition in East Donegal’.

In the midst of the trouble, Fianna Fáil Senator Bernard McGlinchey had phoned the Department of Justice, telling them that ‘Protestants in St Johnston [are] terrified that they will be burned out tonight’ and asking that ‘there should be a show of strength by the security forces early today’. The Department of Justice also noted that ‘the Gardaí are also being told locally that there are two sides to the question—but … [to] accept the Protestant complaints at the moment’.

In early August the Donegal Orange Order leader David Beattie wrote to Taoiseach Jack Lynch. Beattie explained that local Protestants were ‘particularly concerned at the level of intimidation which has been directed against Protestants in the area for the past 2/3 years and the fact that eleven families have felt compelled to leave their homes and seek refuge in Northern Ireland may well be the beginning of a general Protestant exodus’. Beattie confirmed that the Provisional IRA had approached him, disclaiming all responsibility for the violence and offering protection to local Protestants. The Ulster Defence Association in Derry had also offered assistance. Beattie assured the taoiseach that ‘we have politely refused both offers as we would prefer to rely, in the first instance, on the protection of elected government forces’. He concluded by asserting that ‘since the state was formed we have been among its most law-abiding citizens, taking our full part in the social and economic life of the community, and we are entitled to full protection from all forms of attack’. Like much of the violence associated with the Northern conflict that flared up across the South during 1972, the events in St Johnston were not repeated and were largely forgotten.

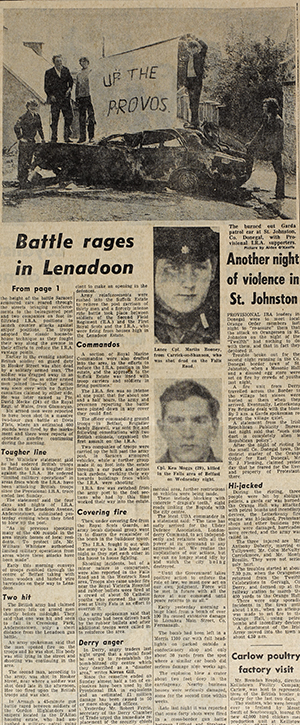

Above: ‘Another night of violence in St Johnston’. (Irish Press, 14 July 1972, p. 4)

The riot in St Johnston emerged during a period of wider tensions relating to the violence across the border. East Donegal had a substantial Protestant population as well as a tradition of Orangeism. Trade unionist George Hunter recalled that during the 1960s woollen-mill workers in the area were ‘50/50 Protestant and Roman Catholic’, and many that were union members were also ‘members of the Orange Order … all of East Donegal had this kind of religious divide, which always had to be taken into consideration when organizing’. The so-called ‘Protestant vote’ was also held to be a significant factor in local politics. As the situation in Northern Ireland escalated, dormant tensions began to be aroused. During the June 1969 general election, Bertie Boggs, a Fine Gael candidate from a Protestant background, was confronted with charges that he was a supporter of Ian Paisley. Roads in Inishowen were painted with slogans proclaiming ‘Vote Boggs No. 1: No Pope Here’, and rumours circulated that Boggs, a councilor in Malin town, was a B-Special and had been among the mob who attacked civil rights marchers at Burntollet. Boggs vigorously denied this and claimed that he was the victim of a smear campaign by elements in Fianna Fáil. He was not elected. (Similar claims were made during the election about Fine Gael’s successful candidate Billy Fox in Monaghan.) During August, with feelings running high after events in Belfast and Derry, threats were sent to several Donegal Protestants from a group calling itself the United Catholic Front. The letters accused the recipients of being B-Specials. A petrol bomb was also thrown into the home of one of those who received a threatening letter, Ivan Knox in Ballybofey. (Knox, a Presbyterian, offered to donate £500 to the Society of St Vincent de Paul if anyone could prove that he was a B-Special.) Condemning these threats, Ruairí Ó Brádaigh of Sinn Féin asserted that since ‘hundreds’ of these letters had been sent to Donegal Protestants, ‘one couldn’t help being driven to the conclusion that there was some form of organization behind it. That was clear especially when these letters were often addressed to people by their colloquial and nick names.’ The belief that local Protestants were members of the B-Specials was also echoed from republican platforms. Strabane activist Ivan Barr told a rally in Lifford that they were ‘aware that men were coming across the border, donning uniforms in Strabane and taking out rifles’, but ‘if they are attacked or interfered with on this side of the border it will bring retaliations in Strabane. Leave them alone for now.’ (These claims, and similar incidents of threats and sectarian attacks, occurred in other border counties and as far south as Wexford during August 1969.)

![Above: Fianna Fáil Senator Bernard McGlinchey (centre) with Capt. James Kelly and his wife Sheila during a lunch break at the Arms Trial, 16 October 1970. In the midst of the St Johnston trouble in July 1972 he had phoned the Department of Justice, telling them that ‘Protestants in St Johnston [are] terrified that they will be burned out tonight’. (captainkelly.org)](https://www.historyireland.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/10/McGlinchey.jpg)

Above: Fianna Fáil Senator Bernard McGlinchey (centre) with Capt. James Kelly and his wife Sheila during a lunch break at the Arms Trial, 16 October 1970. In the midst of the St Johnston trouble in July 1972 he had phoned the Department of Justice, telling them that ‘Protestants in St Johnston [are] terrified that they will be burned out tonight’. (captainkelly.org)

Tensions arose again during the summer of 1970. Rossnowlagh was the site of an annual Orange march, which usually passed off without incident, but Fianna Fáil’s Bernard McGlinchey predicted trouble if it was allowed to go ahead. He claimed that Orangemen had crossed the border the previous August ‘to help B-Specials in their foul work’, and alleged local involvement in the recent UVF bombing of an RTÉ mast at Raphoe. Republicans, however, defended the Orangemen’s right to march, Ruairí Ó Brádaigh blaming ‘Blaneyite’ elements for introducing tension into what he described as ‘a completely harmless affair’. Nevertheless, the parade was cancelled and it was not until 1978 that another took place at Rossnowlagh. In the midst of the controversy an attempt was made to burn the Orange hall in Lifford. As conflict escalated across the border such incidents increased, with several attacks on Donegal Orange halls. In January 1971 the home of the Church of Ireland rector at Tamney was damaged by an explosion, and after Bloody Sunday the Congregational church in St Johnston was fire-bombed. Tensions were also exacerbated by Loyalist activities in the county.

Loyalist attacks in Donegal

Above: Orangemen at the Rossnowlagh parade in 2016. Following predictions of trouble from Senator McGlinchey, the 1970 parade was cancelled and not resumed until 1978. (ITV)

Brian Hanley is a historian and author.

FURTHER READING

Farset Community, Separated by partition: an encounter between Protestants from East Donegal and East Belfast (Belfast, 2000).

Houses of the Oireachtas, Reports of the Independent Commission of Inquiry into the Dublin and Monaghan Bombings (Dublin, 2003–6).

D.R. O’Connor Lysaght, 100 Years of Liberty Hall (Dublin, 2009).

H. Patterson, Ireland’s violent frontier: the border and Anglo-Irish relations during the Troubles (Basingstoke, 2013).