REPUTATIONS: Roger Casement and the history question

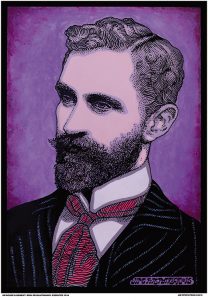

Published in 20th-century / Contemporary History, Features, Issue 4 (July/August 2016), Volume 24IRRESPECTIVE OF THE QUESTION OF THEIR AUTHENTICITY, IT IS NOW UNIVERSALLY AGREED THAT THE BLACK DIARIES WERE INTEGRAL TO A SMEAR CAMPAIGN CONJURED UP IN 1916 TO RAILROAD CASEMENT TO THE GALLOWS AND DENY HIM THE MORAL HIGH GROUND THAT HELPED TO JUSTIFY THE IRISH REBELLION.

By Angus Mitchell

One bold deed of open treason: the Berlin diary of Roger Casement 1914–1916 becomes my third edited volume in the retrieval of the Casement archive. This project began back in 1997 with the publication of The Amazon journal of Roger Casement and was followed by Sir Roger Casement’s heart of darkness (reviewed in HI 11.4, Winter 2003). These initial two volumes enabled a deeper reading of the critical years 1910 and 1911. This third edition covers Casement’s time in Germany following the outbreak of the First World War. Cumulatively, the volumes provide insight into one of the more complex and misunderstood Irish activists of the revolutionary generation and his internationalism. On another level, the texts facilitate a new way of analysing the Black Diaries’ controversy (see HI 9.2, Summer 2001, pp 42–5).

One bold deed of open treason: the Berlin diary of Roger Casement 1914–1916 becomes my third edited volume in the retrieval of the Casement archive. This project began back in 1997 with the publication of The Amazon journal of Roger Casement and was followed by Sir Roger Casement’s heart of darkness (reviewed in HI 11.4, Winter 2003). These initial two volumes enabled a deeper reading of the critical years 1910 and 1911. This third edition covers Casement’s time in Germany following the outbreak of the First World War. Cumulatively, the volumes provide insight into one of the more complex and misunderstood Irish activists of the revolutionary generation and his internationalism. On another level, the texts facilitate a new way of analysing the Black Diaries’ controversy (see HI 9.2, Summer 2001, pp 42–5).

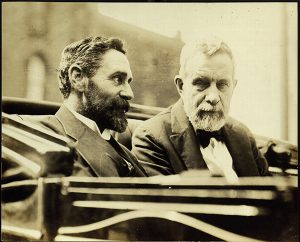

Above: Casement with John Devoy, leader of Clan na Gael, in New York during the July crisis of 1914, where the Berlin diary narrative begins. (Villanova University)

In his Berlin diary, Casement divulges his deeper political intentions behind diary-writing. On his departure from Germany for Ireland in April 1916, he left clear and explicit instructions for the safekeeping of this document, despite the fact that it was intentionally self-incriminating and explained the logic behind his treason. In his own words, the reader is led into an entangled conspiracy against his former British Foreign Office colleagues. The narrative begins during the July crisis of 1914, with Casement arriving in New York (spied on from every side) to liaise and plot with the Irish Republican Brotherhood executive. His own credibility with other revolutionary leaders reaches a high point in the wake of the successful landing of guns at Howth and Kilcoole. In late October, after leaving the US, Casement passed through Christiania (Oslo) on his way to Berlin. By then he had become a high security risk and efforts were made by British secret services to have him ‘knocked on the head’—in short, assassinated.

Above: Recruits to Casement’s Irish Brigade pictured in Germany—half of the total of 56 who joined up. His largely futile efforts to raise an Irish Brigade caused him deepening levels of frustration. (NMI)

In Berlin, Casement entered into a long process of negotiations with different tentacles of Imperial Germany’s wartime government. His journey through Belgium to the Western Front to meet senior officers in the German general staff is described. He details his subsequent conversation with the chancellor, Theobald von Bethmann Hollweg, and other senior politicians. His largely futile efforts to raise an Irish Brigade display deepening levels of frustration. The diary cuts out from late February 1915 to March 1916; then it revives as Casement prepares to leave Germany for Ireland to try and stop the rebellion or stand and die beside his comrades.

Beyond what the diary tells us of Casement’s ‘treason’, the narrative provides intriguing insight into the covert world of both British and German wartime intelligence agencies. His heated encounters with the German spymaster Rudolf Nadolny (grandfather of the acclaimed German novelist Sten Nadolny, author of The discovery of slowness) afford insight into the inner workings of the Prussian war machine. On another level, the deepening intrigue exposes further motives as to why the question of Casement’s diaries persisted as an issue. In the course of his Berlin confession, Casement describes how he consciously forges extracts from his diary in a scheme to deceive the British Foreign Office. When lengthy excerpts from the Berlin diary were published in the US, Ireland and Germany during the signing and implementation of the Anglo-Irish treaty between November 1921 and February 1922, the spectre of the Black Diaries returned.

Homophobia

In a sense Casement was a ‘gay martyr’: the incitement of popular homophobia was intrinsic to ensuring his execution and denigrating his meaning among his national and international networks of support. Moreover, there are revealing links between his trial and the later negotiations of Irish independence. Casement’s prosecutor, Lord Birkenhead, and his defence solicitor, George Gavan Duffy, were both signatories of the Anglo-Irish Treaty. Authentication of the Black Diaries became part of the secret negotiation in the background to the treaty. Their endorsement was part of the secret history of the Irish independence struggle. Why else would Collins have opened an official file series in 1922 labelled ‘Alleged Casement Diaries’?

This set the Irish state down the road of a deeply ambivalent relationship with both the Black Diaries and Casement. On one side, there was a need to recognise the role that Casement played in the move towards and justification of rebellion and as a founding father of an independent Irish foreign policy. On the other side, accepting the authenticity of the Black Diaries was an undisclosed element in the Irish Free State deal. This unplayable hand would define the dispute over Casement’s legacy in the Anglo-Irish history wars of the next century and culminating in this year of commemoration.

In England, the diaries helped in a different type of cultural construction, leading to the disremembering of Casement within British imperial history. After years of denial of their very existence, the Black Diaries passed in 1959 into the custody of the Public Record Office, rebranded today as the National Archives (UK). Researchers seeking access were carefully vetted by the Home Office and required permission from the incumbent home secretary. On the return of Casement’s bones to Ireland in 1965, a further understanding was agreed between London and Dublin that essentially closed down open discussion on the diaries’ controversy for another 30 years.

Psychological biographies

During that period, public consensus regarding the veracity of the Black Diaries was built through the publication of a steady stream of psychological biographies that locked the Black Diaries into the heart of Casement’s life. This intervention primed Casement to become a ‘gay icon’ as much as a national liberator. But messages remained mixed.

In the summer of 1994, on the release of the Black Diaries into the public domain, Professor Paul Bew wrote a controversial article in History Ireland (HI 2.2, Summer 1994, pp 41–5) arguing unequivocally for the authenticity of the diaries. A few months later, Professor Stephen Howe, reviewing Edward Said’s Orientalism for the New Statesman (24 February 1995), commented that ‘the diary was almost certainly forged by the British government to aid in railroading Casement to the gallows’.

Howe’s comment hinted at a ‘knowingness’ or subjugated knowledge that has informed the view about Casement from within the historical academy. But in Howe’s Ireland and empire (2000) Casement received passing mention, despite a deepening recognition amongst post-colonial theorists of the latter’s damning critique of western imperialism. Tension and dissonance within élite academic circles was set to continue.

Publication of The Amazon journal in 1997 had drawn attention to the fact that there was much confusion over the relationship between ‘Black’ and ‘White’ diary narratives describing the same 75-day period during 1910 when Casement investigated the activities of a British-owned Peruvian rubber company. This opened up the controversy to another kind of scrutiny that was scholarly and textual and not politically constrained and luridly sexual. The Amazon journal demonstrated how Casement was deconstructing the racist logic of empire. His incisive analysis exposed the gender-based violence supporting international venture capital. To a shocked metropolitan audience, he revealed the resource wars fought in the name of civilisation against peaceful, indigenous communities and their environments. The fact that the Black Diaries configured so precisely with his investigations into atrocities in the Congo Free State in 1903 and in the north-western Amazon in 1910 and 1911 was becoming their most revealing weakness.

Proustian hero?

It is now evident that the Black Diaries have enabled their own form of epistemological violence, whereby Casement’s achievement as both a pioneer of human rights and a whistle-blower could be marginalised by playing the ‘paedophile’ trump. If the Black Diaries are to be placed centre stage to their biographical subject, then their author, even in today’s terms, was not engaging with ‘hospitable bodies’ but was using his position in deeply exploitative power games. Revisionist efforts to try and turn the sexualised Casement into a kind of Proustian hero, or a gay role model, do not stand up to rigorous scrutiny of the texts. Besides the homophobic world in which they were conjured, the diaries are deeply racist. By manipulating meaning, they demean the authority of the investigator. Casement’s cultural construct as an urbane and playful cosmopolitan queer has little to do with the encrypted distortions evident in the sexualised version of events.

Like other revolutionary leaders involved in 1916, Casement was acutely aware of his place in history and the centrality of the written word to that place. As a British civil servant, he was aware, too, of the role of the archive in the production of history. I have long argued that his most subversive act was to leave on the official record an indelible indictment of colonial power: a denunciation that western historiography is still reluctant to acknowledge. Heading towards his own violent end on the scaffold—with the role of sexuality in the demise of both Parnell and Wilde still in living memory—is it really probable that he would have so conveniently left the ingredients for the subversion of his pioneering investigations? In any interrogation of the Black Diaries, questions to do with motive and probability weigh heavily on the side of forgery.

At the state’s commemoration at Banna Strand on 21 April 2016, the British ambassador to Ireland, Dominick Chilcott, when interviewed by Radio Kerry, claimed that Casement’s ‘memory was lost in the [British] national consciousness’. Part of the process for that disremembering has been accomplished through the presence of the Black Diaries. Another motive for the forgery was to cover up a huge crime against humanity: a destruction of communities and environment that stretches from the upper Congo to the north-west Amazon to the destitute fringes of Connemara. Millions of dead souls—souls without history—haunt the shadows of Casement’s tragedy. In his challenge to the imperial order, Casement blew the whistle on this catastrophe, and his engagement with revolutionary politics was a way by which he articulated his deepest sense of outrage against the system.

‘Dangerous memories’

Britain’s example of disremembering operates in direct opposition to what the theologian Johann Metz has described as the need to collectively connect with ‘dangerous memories’. Casement is one such memory. Engaging with his life and death demands that we critically confront the victims and suffering created by the complacent structures of western power. His life opens up challenging perspectives on history and remembrance and their continuing interaction.

Surely if the Republic of Ireland is now ‘mature’ enough to welcome the British monarch into its midst, then the UK’s National Archive, without pageantry, can reattribute the Black Diaries. Thereby acts of interpretative violence can cease and Casement can be accepted as a rebel with a cause, whose memory should hold historic value and respect on both sides of the Irish Sea and beyond.

Angus Mitchell lectures in the Kemmy Business School at the University of Limerick.

FURTHER READING

R.F. Foster, ‘History and the Irish Question’, Transactions of the Royal Historical Society 33 (1983).

P. Hoare, Wilde’s last stand: decadence and conspiracy and the First World War (Duckworth, 1997).

A. Mitchell, ‘Phases of a dishonourable phantasy’, Field Day Review 8 (2012).

Angus Mitchell’s writings on Roger Casement can be accessed through his academia.edu site: https://limerick.academia.edu/AngusMitchell.

Read More:

The Black Book of 47,000 names