Family and finances in fifteenth-century Dublin

Published in Features, Issue 3 (May/June 2014), Volume 22

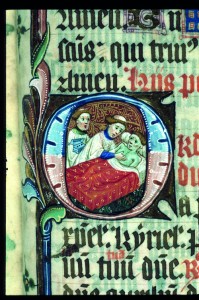

Fifteenth-century manuscript illustration of a monk providing extreme unction to a dying man. Through their wills, people rewarded friendships, ensured the financial stability of their children or spouses, or donated to the church for the sake of their souls. (British Library)

Agriculture, industry and trade

View of St Audoen’s Church through Dublin’s medieval city wall. Richard Boys, a cloth merchant from Coventry who died in Dublin in 1471, bequeathed money not only to churches in his native England but also to St Audoen’s. (Con Brogan/National Monuments Service)

Yet medieval Dublin was home to more than just farmers. William Nele of Clondalkin was a wealthy tanner; John Kempe was owed money by Thady and Peter, who were both blacksmiths. John Barby seems to have been a mercenary in the employment of Philip Bermyngham, the chief justice of the King’s Bench. Barby’s belongings on his death in 1475 included a sword, a sword-belt and two bows. Nicholas Wygth of Lusk kept livestock on a small scale, but his 1474 will indicates that he was primarily a fisherman. He had a quarter share in a fishing skiff, ship’s gear and twelve sea-nets. Debtors owed him ‘hooks of lent tackle’—used to manoeuvre a large sail under a stiff gale—and large quantities of fimble hemp, used to make ropes, cables and sailcloth. Agnes Laueles, who died three years later, seems to have been a brewster. Many medieval women made and sold small ale (a weak beer that was consumed widely in an age before safe water supplies) from their home in order to supplement their family’s income. Agnes left a ‘losset’, or kneading trough, to her daughter Joan, and a mash tub to her other daughter, Rose.

Merchants, both Irish and foreign, were also a fixture in medieval Dublin, making the city part of wider social and economic networks. Richard Boys, a cloth merchant from Coventry, died in Dublin in 1471 on a trading trip. He had trading contacts in Drogheda, Navan and Trim as well as Dublin, and had clearly spent enough time in the city to bequeath money not only to churches in his native England but also to St Audoen’s in Dublin. In the 1480s Archbishop John Walton drew up a will in advance of an overseas trip. He owed 25 marks to Thomas Halman of Oxford for the purchase of spices, and 250 marks—some £100,000 in today’s money—to two Florentine merchants, Geraldo Cavigiani and Laurencio Barduci.

Local economic activities also created networks of debts and obligations. John Palmer of Kilsallaghan is a typical example. He had 34 acres of grain in the fields, four horses, eight cattle, 90 sheep and eight hogs and pigs. He had some kitchen and brewing utensils, and four gammons hanging in his larder. Despite these resources, he died owing £7 18s 91/2d to various people, including 31 shillings in rent to his lord and 12d to ‘Joan the nurse’—roughly £45,000 nowadays. Richard White of Swords, who may have been a carpenter or builder, died with many people (from Swords, Lusk, Oberstown and Lispopple) owing him debts totalling £10 11s 7d.

Household goods and family relationships

A fifteenth-century settle (wall bench) and an oak cupboard. Furniture, kitchen utensils and bedlinen were carefully tended and inventoried in people’s wills. (Bunratty Castle Medieval Collection)

Some parents split their property equally among their children: Robert Lanysdall of Balrothery made some minor bequests to religious institutions, but the bulk of his estate was to be divided between his three daughters. Some surviving wills hint, however, at family conflict. Cecily Langan, writing her will in early 1474, didn’t leave equal shares of her property to her daughters. Ellen received a brass pot and a heifer; Katherine received the same, plus two measures of wheat and malt; Alice, however, had to be content with a single pan. Nicholas Barret, who sought burial in the church of St Michan’s, also left behind a will that implies family strife. His will states that the year before his death he handed over several items to his daughter Joan—brass cooking vessels, six silver spoons, a red cow and assorted household items—and wanted her also to have £10 as a dowry. One son, Thomas, was to inherit all the family’s property in Finglas. In contrast to this generosity, however, Nicholas’s other son, John, was to receive ‘a small pot with a broken leg’. Similarly, Peter Higeley’s will declared that all his property in the city would go to his son Thomas so long as his other son, Patrick, was not ‘of good conduct and governance’; only if Patrick reformed would he share in the property with Thomas.

Life in an age before antibiotics or sanitary childbirth could be short. Two wives of Geoffrey Fox wrote wills—Jonet Cristore in 1473, and Agnes Laueles, the brewster, in 1476. Jacoba Payn, the wife of John Kyng, requested on her death in late 1475 to be buried in the cemetery of St Patrick’s Cathedral near to her first husband, Thomas Paryse. She herself was Kyng’s second wife; her will explicitly states that it disposes only of the goods that had been presented to her and which did not belong to Kyng or his deceased first wife. To her daughter, Matilda, Jacoba left a large brass pan, two silver-studded girdles, jewellery and a maser cup. To her cousin Margaret she left six shillings, and to Margaret Mey she bequeathed a ‘coat of Irish cloth’.

Lively wakes

Other bequests focused more on the community. Many people were concerned with ensuring that they would have a lively wake. Margaret Browneusyn of Killadoon left eight shillings for bread, eight shillings for ale and ten shillings for meat. William Power of Ballymadun left two shillings for burial rites and 40d for wax candles, but also four measures of wheat for bread, six measures of malt for brewing, and a cow and a hog to provide meat. Some bequests are perhaps a little puzzling to modern eyes. Joan White, who died at Leixlip in early 1473, left the usual amounts to pay for the funeral and for refreshments at her wake, but she also left a ‘three-legged pan and one trough with two trundles’ for her neighbours’ use. Nicholas Delaber left his ‘largest pot and skillet so that they may pass in common among all living in Balrothery, as well rich as poor’.

Other bequests focused more on the community. Many people were concerned with ensuring that they would have a lively wake. Margaret Browneusyn of Killadoon left eight shillings for bread, eight shillings for ale and ten shillings for meat. William Power of Ballymadun left two shillings for burial rites and 40d for wax candles, but also four measures of wheat for bread, six measures of malt for brewing, and a cow and a hog to provide meat. Some bequests are perhaps a little puzzling to modern eyes. Joan White, who died at Leixlip in early 1473, left the usual amounts to pay for the funeral and for refreshments at her wake, but she also left a ‘three-legged pan and one trough with two trundles’ for her neighbours’ use. Nicholas Delaber left his ‘largest pot and skillet so that they may pass in common among all living in Balrothery, as well rich as poor’.

The wills contained in the Register show us a society concerned with preserving its stability and orderliness for future generations. Medieval Dubliners managed their households, tilled their land and carried out trade. They formed alliances, friendships and marriages, and they used wills to bolster what they had created. These wills are more than just dry legal records—they are a window into the lives of middle-class Dubliners at the end of the fifteenth century.

Yvonne Seale is a Ph.D candidate in history at the University of Iowa.

Read More: Wills as historical sources

Social display and charity

Further reading

P. Connolly, Medieval record sources (Dublin, 2002).

Register of wills and inventories of the Diocese of Dublin in the time of Archbishops Tregury and Walton, 1457–1483 (Dublin, 1898).