Museum Eye

Published in Issue 1 (Jan/Feb 2007), Reviews, Volume 15

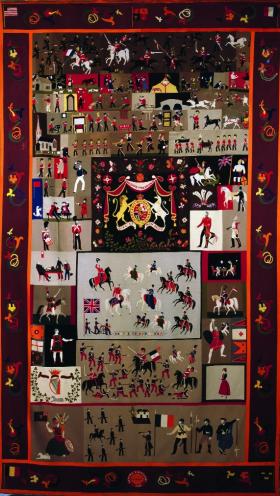

The Stephen Stokes Tapestry.

Soldiers and chiefs, the Irish at war

National Museum of Ireland Collins Barracks, Dublin

Tues.–Sat. 10am–5pm, Sun. 2pm–5pm (closed Mon.)

by Tony Canavan

This is an ambitious exhibition that undertakes to present the history of the Irish at war from 1550. It is suitably located in Collins Barracks, where it occupies 1,700 square metres of space. Various aspects of our military heritage are represented, from the native armies and Wild Geese to service under the British flag.

The entrance is guarded by glass panels on which are engraved Irish soldiers from various years in history, each with a voice that recounts something of his or her (there is one female figure) story, such as going off to fight Napoleon or defending Irish neutrality during the Second World War.

The first gallery depicts ‘The British Garrison in Ireland’. All the galleries are presented in the same way. Alongside cabinets filled with artefacts—uniforms, weapons, personal effects and so on—are information panels, interactive touch-screens, manikins and models. The main panel here tells us that there was a garrison in Ireland for 500 years and that it was ‘here primarily to suppress revolts’. All aspects of the garrison, from its forts and barracks to its sporting and social life, are represented. Subsections show how soldiers mixed with the locals and how some married and settled down here. We learn, too, how important the garrison was to the economy. It provided employment and supported businesses, since soldiers had to be supplied with food, clothes, furniture and services, including prostitution. The centrepiece of this gallery is the Stephen Stokes Tapestry, which records major events in his long life as a soldier. The tapestry was quite a talking-point in its day, and was even shown to Queen Victoria. The touch-screen will certainly appeal to the younger visitor as you can bring it ‘to life’ complete with sound effects.

The next gallery deals with warfare in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. The manikins here representing soldiers from the various wars are especially good, and the 12lb cannon from 1798 impressive. Alongside the items on display, the panels explain each conflict and its outcome. I have to say, however, that there was more to the Irish defeat at Kinsale in 1601 than the lack of stirrups, as one panel asserts. It is interesting, too, that one of the panels speculates on the ‘What if?’ (‘Ceard faoi?’) of these wars.

Other rooms examine the Irish in foreign armies. We have the story of the Wild Geese and Irish solders in the American Civil War, but also of the soldiers and sailors who served in Latin America, Russia and elsewhere. At different places you can press a button and hear a contemporary account of some event, such as the execution of the Irish who fought for Mexico. The centrepiece here is a video giving an exciting and evocative account of the Battle of Fontenoy.

The following galleries concentrate on the Irish, the many thousands, who served in the British Army in the nineteenth century. A key role for these regiments was maintaining the British Empire, and this is reflected in some of the items, such as an Afghan rifle and a Burmese gong. The enemies of the ‘Imperial Irish’ are represented by the Irish Brigade, who fought for the Boers. The most popular display, however, is the weapons’ range. Here you can lift a Brown Bess, Martini Henry or Lee Enfield rifle, and a drill sergeant appears on screen to instruct you on how to use it. Boys of all ages (including me!) lined up to have a go.

Next is a section on the First World War. To get there you have to cross above another gallery, which gives you the chance to look up close at a Vampire fighter jet. The atmosphere becomes more sombre in the First World War gallery, where the enormity of the conflict and the loss of life are brought to bear. Displays on the main battles, like the Somme or Gallipoli, and the cases with uniforms and equipment stand alongside others holding personal mementoes such as a cigarette box or the photo of a sweetheart.

Ford armoured car, used by Irish troops in the Congo.

The room divides here, and so might opinions on it, as the visitor steps into a section devoted to the 1916 Easter Rising. Here is much of what was in the 1916 exhibition in Kildare Street, but it has been added to and is better displayed. We get an idea of what the Rising was about and of the people involved. One poignant item is the blood-stained undershirt worn by James Connolly.

From here you go on to a section on ‘The Irish Wars’, i.e. the War of Independence and the Civil War. This is an excellent exhibition that really conjures up the atmosphere of street warfare in Dublin as Collins’s squad and Dublin Castle’s agents fought it out. Good use is made of contemporary newsreel and artefacts to bring this period, and the Civil War, to life. Little or no mention is made of Partition and the fighting in Northern Ireland at this time, however.

The final sections of the exhibition take us up to present-day service with the United Nations. Touch-screens evoke the army at different periods, particularly during World War II. It is interesting to note that the Irish newsreels of the time, and presumably everyone else, referred to the ‘world war’ and not the ‘Emergency’, as some historians would have us believe. We are reminded that pomp was once a feature of the defence forces in the officers’ dress jackets and the uniform of the Blue Hussars. There are all sorts of equipment and vehicles on display, but don’t forget to look up to see the planes from underneath this time. It has its serious side too, however, particularly when the price of peacekeeping is considered, as reflected in the small but evocative display on the Congo.

I left very impressed by this exhibition and have no hesitation in recommending it. I have one or two minor quibbles, such as that some of the labelling is sloppy. I have one

Panhard M3 armoured personnel carrier, currently used by Irish troops on UN duty, with a de Havilland DH 115 Vampire ‘flying’ overhead.

(All images, National Museum of Ireland)

serious concern—the exclusion of Northern Ireland. By any standard, Northern Ireland and its conflicts (remember that Northern Ireland did not enjoy one whole decade of peace in the twentieth century) should be included in this exhibition of ‘the Irish at war’. I think it a legitimate question to ask why it is excluded.

Tony Canavan is a former Museum Officer of Newry and Mourne District Council.