Subtracting insult from injury: he medical judgements of the Brehon Law

Published in Features, Issue 5 (Sept/Oct 2011), Medieval History (pre-1500), Volume 19

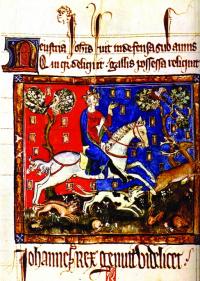

Fourteenth-century depiction of King John, who introduced English Common Law to the lordship of Ireland in 1210. (British Library)

In 1210 King John ordered that English Common Law was henceforth to be the law of the Norman lordship of Ireland. The Common Law was a centralised system of justice with civil and criminal divisions, and trial by jury. The Irish, who were deemed ‘rebels’, used the Brehon Law instead until the seventeenth century. Under the 1604 Act of Oblivion, the ‘Irishry’ were pardoned for their offences and ‘received into His Majesty’s immediate protection’. By 1617 English law assizes were held twice yearly in all counties of Ireland.

Brehon Law

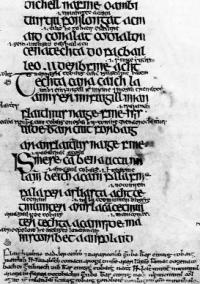

The Brehon Law was the legal system that existed in Ireland before the coming of the Normans. These ancient laws were transmitted orally until literacy arrived with Christianity in the fifth century. The Brehon Law was evolved by judges (brithem) and reflected the complexity of early Irish society. There was no distinction between criminal and civil law, and initiating legal action was the responsibility of the injured party or his kin to the fourth generation (derbfine). There were no juries and almost any crime could be atoned for by the payment of a fine or compensation.Between the fifth and twelfth centuries Ireland comprised some 120–160 kingdoms (túath), each having a population of about 3,000. D.A. Binchy described early Irish society as ‘tribal, rural, hierarchical and familiar’ (i.e. based on the family). Each túath had a king (rí), an ecclesiastical scholar (ecnae), a poet (file), a historian (senchaid), a judge (brithem túaithe) and a physician (liaig). Distinctions were made between those who were privileged (nemed) and those who were not, and between the free (sóer) and the unfree (dóer). The arrival of Christianity influenced Irish society, but the Roman concept of equality before the law was not established, and judgement depended on status. Law enforcement was achieved by systems of sureties, pledges and distraint, based on equity and precedent, rather than by central enforcement. The most important collection of old Irish law texts is known as the Senchas Már, ‘great tradition’. Nemed is another collection, while a few texts seem to stand alone, e.g. Críth Gablach. Many of the primary law texts were written down between 650 and 750, but the extant texts were compiled between 1300 and 1600 in law schools. The laws are written in Old Irish but the later scribes added interlinear glosses or explanations, as well as commentaries, in Middle Irish. The interpretation of the surviving manuscripts is therefore difficult; one scholar wrote: ‘my translation of the text . . . must be regarded as purely tentative’.

A page from a fourteenth-century legal manuscript. The text in large lettering is the actual law, while the smaller text is an explanation or gloss of the law. The text at the bottom of the page is a commentary on the law. (Trinity College, Dublin)

Medicine in Gaelic Ireland

Physicians practised in Ireland from earliest times. The Book of Genealogies lists Capa and Eaba as the first male and female doctors in Ireland. The first historical reference to a physician is in the Annals of the Four Masters, where the death of Maelodhar Ua Tindridh, ‘the most learned physician of Ireland’, is recorded in 860. Medicine was a hereditary profession. In post-Norman Ireland specific families were physicians to ruling dynasties. Exactly how physicians were trained is unknown, but early medical schools existed, such as at Aghmacart in modern County Laois. In the schools, leech books were compiled and contemporary European medical texts were translated. The trained doctor (midach téchtae) had status in the túath, but masters (ollam) and unqualified physicians (midach étéchtae) were also known. Healing by the use of herbs was very important, but the qualified physician was allowed to shed blood (fuil midaig téchta), a possible reference to surgery. If a physician was not fit to practice, he was distrained by the removal of his lancet (fraig) and horsewhip (echlasc), and by the tying of a thread round his ring finger. Physicians’ fees were based on the wounds sustained and the status of the patient.

Medical judgements

While most of the law texts deal with status, property and contracts, a number of the texts are of medical interest. Bretha Déin Chécht (Judgement of Déin Chécht), Bretha Crólige (Judgement of Blood Lying) and Di Ércib Fola (Fine for Bloodshed) all deal with medicine. Déin Chécht (leech) was one of the craft gods of the Tuatha De Danann; the others were Goibniu (smith), Luchta (wright) and Credne (metal-worker).The medical texts prescribed the level of compensation to be paid to a victim and the care of the injured.

D.A. Binchy, who published the Brehon Laws as the Corpus Iuris Hibernici in 1978, described early Irish society as ‘tribal, rural, hierarchical and familiar’. He is pictured here in his role as Irish minister to the Weimar Republic from 1929 to 1932. (Bundesarchiv)

A person who assaulted another unlawfully was liable to pay a fine (éric or corpdíre) for the injury plus an honour-price based on the status of the victim. The offender also had to provide sick-maintenance (othrus), i.e. to look after the victim until he or she had recovered. Legally inflicted injuries (e.g. in self-defence) were not liable for othrus and were called fuil slán (free blood). Minor injuries did not carry any obligation to provide othrus but the perpetrator had to pay the éric for the injury, calculated as a fraction of the fine for homicide.A person accused of inflicting an injury was required to agree to abide by the rule of the court. The plaintiff’s allegation was admitted or denied by the defendant. If denied, the plaintiff called witnesses and made a formal oath asserting the truth of his allegations, supported by three ‘oath-helpers’. The defendant then gave his version, supported by witnesses and ‘oath-helpers’. In this hierarchical society a king’s oath outranked the oath of a freeman, and a churchman’s oath topped all others. If a verdict could not be determined on the evidence, it was established by drawing lots, by ordeal or by duel. Three pieces of wood (corcrann) were used as lots to decide the verdict: ‘guilty’, ‘not guilty’ or ‘not proven’. The common ordeal used was fir coiri or the ‘proof of the cauldron’. The suspect immersed his hand in a cauldron of hot water; after a specified time, the hand was examined and guilt determined by the presence of scald marks. A duel was conducted before witnesses and the winner was deemed to have justice on his side. Having identified a guilty party, the éric, the honour-price and sick-maintenance costs were decided.

Redwood Castle, Co. Tipperary, site of the law school maintained by the Mac Aodhagáin clan, who were hereditary brehons.

A very detailed classification of wounds existed, based on the site and severity of the wound. The éric was calculated on the wound and on the status of the victim. The physician’s fee was 50% of the éric for wounds to any of the ‘twelve doors of the soul’, which were defined anatomical sites, e.g. the top of the head. The same was true for any of seven distinct fractures, e.g. of the femur, or for wounds inflicted in seven different situations, e.g. in battle. The severity of the wound was also classified. There was an increasing scale of fines, based on the type of injury sustained, ranging from two séts for a ‘white blow’ (mbanbeimen) to 21 milking cows for homicide (croligiu chuntabartach báis).Nine days after the injury, a determination was made on the wounds inflicted (derosc cacha fola). A physician gave a prognosis with four possible outcomes. (a) The injured person had died: the defendant was liable for the éric for homicide, which was paid to the victim’s nearest relatives, plus the honour-price, paid to the derbfine. (b) The injured person had made a full recovery: the defendant paid the éric according to the nature of the wound; a permanent blemish/disability carried an extra fine. (c) The injured person was unlikely to recover: this was crólige mbáis and the defendant was liable for a fine similar to the homicide fine. (d) The injured person was likely to recover: this was fuil othrusa; the defendant was obliged to remove the victim (dingbáil) to a place where he could be nursed back to health under medical supervision. If he subsequently died, the rules for crólige mbáis applied.

The ruins of Culahill Castle, Co. Laois, near which the medical school of Aghmacart existed during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries.

Nursing care

There was an obligation on the guilty person to provide proper nursing care and a work-substitute for the victim. There was a duty on the victim to accept the standard of care due to him and to resume his normal role immediately when cured. In the presence of witnesses, the injured person was taken to a safe place for nursing care—if a cleric to a monastery, if a layman to any place deemed suitable for othrus, e.g. not the dwelling of the defendant or a place where the wounded individual feared further injury. It was stipulated that the sick man should be

‘. . . taken to a proper house with four doors (ceitri dorais ass) so that the sick man may be seen from every side, and water across the middle of it (ocus uisci tar a lar); that fools or female scolds be not let into the house and that he not be injured by forbidden food’.

The food to be provided to the injured party during othrus was described in great detail. The guilty person also had to provide for the invalid’s retinue while on othrus; each attendant was entitled to one loaf of bread daily and appropriate condiments. The invalid’s friends were entitled to visit every ninth day and they, as well as the leech, had to be entertained at the expense of the guilty host. Even as the law texts were being written, however, a change in the system was occurring. In one text it is stated that

‘Sick-maintenance does not exist at the present time, but rather the fee for his worthy qualities [is paid] to each according to his rank, including leech’s fee and ale, and refection (tincisin), and also the fee for blemish, hurt, or loss of limb’.

Thus the onerous orthus regulations seem to have been converted into a nursing fee, which was equivalent in amount to the honour-price of the injured party. The victim was then nursed back to health in his own home. In pre-Norman Ireland there was no centralised system of law enforcement. If a fine was not paid, the law allowed an individual to enforce his claim by seizing the plaintiff’s goods (athgabál) or taking possession of land (tellach). In the case of murder, the murderer could be executed or sold into slavery by the victim’s relatives. The church was much keener on physical punishment than the secular courts. Hanging (crucifigi), death by starvation in a pit (góla) and slaying with a sword (guin) were all used.

The end of the Brehon Law

The Tudor conquest of Ireland and the flight of the Irish earls in 1607 saw the end of Gaelic society and its support for knowledge-based professions, including law and medicine. In 1608 the Gaelic succession laws of gavelkind, ‘where the bastards had their portions as well as the legitimate’, and tanistry, whereby succession passed to an elected tánaiste rather than by primogeniture, were abolished. The medical school at Aghmacart disappeared in 1611, and all the Irish law schools were extinct by the eighteenth century. Thereafter, Irish doctors trained overseas and the formal medical and legal structures of Gaelic Ireland disappeared. HI

Pierce A. Grace is Professor of Surgical Science at the University of Limerick.

Further reading:

T.M. Charles-Edwards, ‘Early Irish law’, in D. Ó Cróinín (ed.), A New History of Ireland, 1. Prehistoric and early Ireland (Oxford, 2010).F. Kelly, A guide to early Irish law (Dublin, 2009).A. Ní Dhonnchadha, ‘The medical school of Aghmacart, Queen’s County’, Ossory, Laois and Leinster 2 (2006).