Teaching the Armada: an introduction to the Anglo-Spanish War, 1585-1604

Published in Early Modern History (1500–1700), Features, Issue 5 (Sep/Oct 2006), Volume 14As topics go, the Spanish Armada has everything: great personalities, grand strategy, warfare on land and sea, diplomatic manoeuvres and conspiracies, propaganda in abundance and religions to die for—all available in a rich range of primary sources (documentary, visual and artefactual) and in a variety of secondary literature and websites. Many of the issues involved, though specific to the period, open up general historical questions. The role of political leadership is brilliantly exemplified in the contrasting cases of Philip II and Elizabeth I. Philip was married with heirs, presiding over a world empire faced by many, many threats. Elizabeth was unmarried, heirless and attempting to survive on the throne of a small country in the face of threats first from Mary Queen of Scots and then from the might of Spain. In spite of the wealth of the Indies Philip was in huge debt, but continued to spend heavily on wars to maintain and expand his empire. Elizabeth was a notoriously stingy monarch who had stashed away money as a war chest in the event of hostilities with Spain. Though firm in their religious beliefs, they were both pragmatic in their statecraft. They played off the factions in their administrations against each other and for different reasons were slow to make decisions. Although they concentrated power in their own hands, the decisions they made were very much circumscribed by the limitations of early modern administration. The Spanish monarch is superbly treated in G. Parker, The Grand Strategy of Philip II (New Haven, 1998), and in more narrative and revisionist style by Henry Kamen in Philip of Spain (New Haven, 1998). Elizabeth is the subject of countless biographies of varying quality. The best is Wallace MacCaffery’s life’s work, Elizabeth I (London, 1993), whilst a useful recent series of essays on her reign can be found in Volume 14 of the Royal Historical Society Transactions (Oxford, 2005).

Weakness of France

The Anglo-Spanish conflict is also an exercise in geopolitics and, indeed, a matter of the counterfactual in history (what might have happened). Explaining these strategic considerations to students, coupled with the vagaries of royal marriage policies, can be great fun. The biggest factor in late sixteenth-century politics was the weakness of France. In the 1550s, under Henri II, France was populous and aggressive, compact in geography and central to European power politics. England needed Spain’s alliance against France, especially with the dauphin of France, Francis, marrying Mary Queen of Scots, and Spain needed England in the balance of power against France. But in mid-1559 the 40-year-old Henri II was killed in a jousting match and France descended into weak monarchy, dynastic strife and sporadic religious wars that lasted on and off for 40 years. As a result, England was able to remove the French forces threatening it from Scotland and to back a regime there which in turn forced Mary Queen of Scots, returning home after the death of King Francis in 1560, into two disastrous domestic marriages. The tragic twists and turns of the latter’s career are admirably dealt with in John Guy’s biographical study ‘My heart is my own’: the life of Mary Queen of Scots (London, 2004). Had France continued on its 1550s course, Scotland might have become a French province, as Brittany had done. Furthermore, Elizabeth would have been forced to marry, indeed to marry a relative of Philip II, to stave off the claims of her legitimate Catholic rival, the French-backed Mary. Also Philip’s troublesome Protestant subjects in the Netherlands would never have attracted English support because Elizabeth would have been far too fearful of France taking advantage of the situation there. Besides this, a strong France would never have permitted Philip of Spain to pursue his claim to Portugal with such consummate ease. Portugal was of amazing strategic importance. Its seizure in 1580, after King Sebastian’s madcap crusade to Morocco and the predictable disaster that followed, made possible an invasion of England for the first time because it gave Spain an extended Atlantic sea-coast, a deep-water port at Lisbon and an oceanic naval fleet.

Causes of war

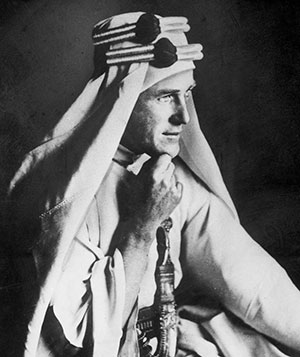

By this time two issues were straining Anglo-Spanish relations to breaking point. The lesser one was the attempt by English seamen as freebooters to break the Spanish colonial trade monopoly; or, more violently, their activities as privateers under licence from hostile governments or as plain pirates to loot the Spanish empire. In this regard the great example is Francis Drake. Having failed to trade legitimately on the coast of Mexico in 1568 and having narrowly escaped the fate that befell his Hawkins cousins, Drake had more success when he attempted to intercept the mule trains carrying silver across the Isthmus of Panama in 1573. But it was his daring circumnavigation (1577–80), passing through the Straits of Magellen, that caught the Spaniards unawares. Queen Elizabeth was a silent partner in this immensely profitable venture and knighted Drake on his return. This was no voyage of exploration but a belligerent act of long-distance piracy!

Despite the aggravations on the high seas, the main problem was the Netherlands, where attempts at religious centralisation had brought protests from the gentry and widespread vandalising and ransacking of churches by Protestant-led mobs. Philip, the sovereign lord of the Netherlands, based in distant Castile, over-reacted and dispatched the duke of Alva with the Spanish army to re-impose order. In fact this had largely been achieved before Alva arrived, but there nevertheless followed a reign of terror against royal opponents and Protestant reformers, many of whom took refuge in England. The arrival of a large Catholic army across the Channel naturally alarmed the newly established and still very nervy Protestant regime in England. When the queen detained Alva’s treasure ships seeking shelter in Southampton in 1568, there was a break in diplomatic relations and embargoes on trade. Relations were not officially restored until 1574, but in the interim Dutch refugees—the famous Sea-Beggars—had used England as a launch pad to mount an attack on Brill in Holland and to ignite a full-scale revolt against Spain. Overstretched, Spanish rule in the Low Countries collapsed. Alva was recalled but a more softly-softly approach was too late. Philip was forced to declare bankruptcy and his unpaid soldiery mutinied, leading to the so-called ‘Spanish Fury’ that devastated the city of Antwerp and decimated its citizenry. By 1577 the Spanish army had withdrawn and William of Orange, the leader of the revolt, was being fêted in Brussels as the liberator of his country.

By the early 1580s, however, the Spanish reconquest was well under way. The final defeat of the Incas in Peru by Viceroy Toledo and his reorganisation of the production of silver there had solved the bullion bottleneck. Truce with the Turks in the Mediterranean freed up troops and resources for redirection northwards. And finally the king had a new and very able governor in Alessandro Farnese, prince of Parma. He won over Catholics in Brabant, re-entered Brussels and moved steadily north, taking town after town. In 1584 William of Orange was assassinated by a loner hoping to collect the money put on his head when the Spaniards declared him an outlaw. On this see Lisa Jardine’s The awful end of Prince William the Silent: the first assassination of a head of state with a hand-gun (London, 2006). English Protestants were themselves fearful for the life of their queen, having earlier discovered the Throckmorton plot, which involved Catholic extremists, the Spanish ambassador and the imprisoned Mary Queen of Scots. Thus when the leaderless and increasingly beleaguered Dutch turned to England for aid, their hopes were high.

A remarkable series of documents to be put before students at this point are the deliberations of the English privy council on war and peace (Historical Manuscripts Commission, Salisbury Papers, III, 67–70). Lord Burghley, with his famous pros and contras, and his fellow councillors have left documents showing arguments for intervening immediately to obstruct the progress of the Spaniards in the Netherlands in the hope of preventing them from overwhelming the Dutch and achieving absolute domination there. Such a confrontation obviously entailed war with the world’s superpower. But if England stood idly by, could she afterwards survive on her own under continuous threat from an even stronger foe? This was the same classic foreign policy dilemma that English statesmen faced with the subsequent French and German threats right into the twentieth century. The privy council favoured intervention but Elizabeth prevaricated in the vain hope that the weak French regime of Henri III might do something for the Dutch instead. After a further series of tit-for-tat maritime provocations, Elizabeth finally signed the Treaty of Nonsuch with the Dutch in August 1585, which involved loans and the dispatch of an expeditionary force under the earl of Leicester. It arrived too late to prevent the fall of Antwerp but it was a contributory factor in the survival of the Dutch Republic.

The ‘Enterprise of England’

An invasion of England to deal with its Protestant queen and her meddlesome subjects, contemplated from the end of Santa Cruz’s operations against Portuguese resistance in the Azores in 1583, now became a top priority. On this Garret Mattingley’s The defeat of the Spanish Armada (Harmondsworth, 1962) remains one of the classics of historical writing. The best material on the events of August 1588, however, emerged at the time of the 400th anniversary and in the decade that followed. In particular, reference should be made to C. Martin and G. Parker, The Spanish Armada (Harmondsworth, 1988), and Simon Adams and Mia Rodríguez-Salgado, England, Spain and the Gran Armada (Edinburgh, 1991), as well as Parker’s master-study of Philip’s strategy, cited above.

Philip authorised studies of former invasions of England and requested proposals from his successful commanders, the marquis of Santa Cruz and the prince of Parma. The former naturally proposed a seaborne invasion whilst the latter came up with the idea of a cross-channel expedition. The big mistake in planning was Philip II’s decision to combine both plans. On the face of it this seemed a masterstroke in that it intended to combine the forces sent from Iberia with the crack army of Flanders into a single massive amphibious assault force. The chances of gaining the best of both were doomed from the start, however, because communications and geography made the necessary rendezvous impossible. Furthermore, there was no ‘plan B’ to fall back on in the event of the rendezvous’s not taking place. When these difficulties were pointed out to the king, all he could do was to advert to God’s assistance in what was after all a holy enterprise.

The preparations were massive. Men, supplies and munitions began to be assembled at Lisbon from all over southern Europe. In Flanders Parma began building barges, and indeed constructing canals, to get his army safely to the coast. Diplomatically Philip was also winning. Pope Sixtus, who had encouraged Philip’s plans in the first instance, was promising a subsidy. The French Catholic League in the pay of Philip worked on emasculating their Protestant and Royalist opponents so as to prevent them from engaging in any independent or diversionary action in the north of France. Philip sought to disarm Elizabeth by mounting false peace negotiations, and even managed to ‘turn’ her ambassador in Paris into a traitor and a channel of false information. Furthermore, Elizabeth’s execution of Mary Queen of Scots in February 1587 following the Babington plot not only gave the Catholic side a massive propaganda boost but also enabled Cardinal Allen to fashion a claim for Philip to the English throne through the Lancastrian line.

All was going well for a summer departure until Drake struck at Cadiz in April 1587. His ‘singeing of the king of Spain’s beard’ involved the destruction not only of 24 ships in Cadiz harbour but also a great quantity of supplies en route to Lisbon. He caused panic all along the Iberian coast and continued on to the Azores, where he caused further damage. As a result, Santa Cruz was sent scurrying after him on a forlorn mission. Chaos reigned, the mission had to be postponed and Santa Cruz sickened and died at the start of 1588.

The Armada was now costing Philip 30,000 ducats per day. The ill-fated duke of Medina Sidonia who replaced Santa Cruz, though much criticised by history, actually proved a brilliant organiser and galvaniser of an expedition that was literally going nowhere when he took charge. Within a matter of months the Armada was back on target. One hundred and thirty ships and 19,000 soldiers had been assembled at Lisbon and a 27,000-strong army was ready to be ferried on 300 small craft through the canals of Flanders into the Channel. There was nothing to equal it in Western history; in global terms only the similarly abortive second attempt at a Mongol invasion of Japan in 1281 was larger. In Rome the pope issued a special indulgence; Cardinal Allen had propaganda tracts printed for distribution amongst English Catholics, and in France the Catholic League drove the king out of Paris. On the first leg of the journey, however, the Armada was battered by storms on the coast of Portugal and was forced into La Coruña. Medina Sidonia, fearful of the difficulties ahead and advised by his fellow admirals, wanted the mission cancelled but the king refused. The duke obeyed orders, and after another burst of organising energy he made the fleet seaworthy once more and was able to put back to sea.

Guns at Gravelines

There is debate about whether Medina Sidonia, intent on following Philip’s orders to the letter, missed a golden opportunity on 30 July to lead a surprise attack that would have trapped the English fleet in Plymouth Sound. But the Spanish command did not know the English navy’s location, and westerly winds were pushing the Armada steadily up the Channel. There followed a series of skirmishes, with the Armada taking up the famous winged formation to protect its diverse range of shipping against the more manoeuvrable English ships. The English, in spite of some hiccups, managed to keep between the Spaniards and the coast and critically denied them an opportunity to anchor in the Solent on 3 August. On the other hand, even though the English were using new tactics of attacking in lines firing broadsides, the Armada experienced relatively few losses and had maintained formation.

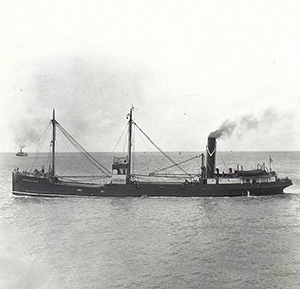

Medina Sidonia had not yet established contact with Parma, however. Although he had sent out messengers in pilot boats as the Armada progressed up the Channel, it was not until 6 August, the same day that the fleet anchored off Calais, that Parma was aware of its approach. Even then it required six days’ notice for the embarkation and departure of his forces. It was in fact ready by 10 August, but the campaign was already over. On the night of 7 August the English sent fire-ships—old hulks loaded with explosive materials—in amongst the Armada ships, which in desperation cut their anchors to escape. The following day, in a nine-hour battle at Gravelines the English closed in on the Spaniards, sinking some twelve ships and killing or wounding 1,800.

Although the Armada, badly mauled, regained formation, the so-called ‘Protestant’ wind was soon blowing it up the North Sea, and Medina Sidonia, unaware that the English had run out of ammunition, made the decision to return home by rounding Scotland and Ireland. On this journey damaged ships began to seek shelter in the Scottish islands, and more headed for the coast of Ireland; and then gales like those that destroyed the Fastnet race of 1979 sent many other vessels crashing into the Irish coast. At least 23 ships were lost there, and over 6,000 men were drowned, killed or captured. About 500 Spaniards survived, however, and made it through Irish-controlled areas of Connacht and Ulster to neutral Scotland. One such was Captain Francisco de Cuellar, who was shipwrecked on Streedagh Strand, Co. Sligo. His famous, and highly coloured, memoir can now be consulted online at http:// www.ucc.ie/celt/published/T108200/index.html.

Despite the terrible loss of life in Ireland, the ships wrecked there have since the 1960s provided archaeological evidence that goes a long way towards explaining the Spanish defeat at Gravelines. Many of these ships, it turns out, still have plenty of ammunition on board, as well as unusable or exploded cannon barrels. Martin and Parker were able to draw significant conclusions. Not only did the Spaniards have substandard guns and assorted ammunition but also, more critically, they lacked the techniques for rapid fire that the English had developed and trained in. Basically the Spaniards preferred the traditional grapple-and-board tactics, and many of their weapons had only been fired once or twice. Students should be taken to see these artefacts in the Ulster Museum, Belfast. While they might be more attracted to the large quantities of gold coins and other ornaments brought up from under the sea, the real historical treasure is in fact the guns and ammunition.

War of attrition

There is, unsurprisingly, a great deal of propaganda, both printed and visual, from during and after the 1588 campaign, not least the queen’s speech at Tilbury, for students to sample and carefully sift. Indeed, there is no doubt that this echoing down the years has given the impression that the war had been won for England on the banks of Flanders. This could not be further from reality. Though the failure of the 1588 Armada had a determining effect on the course of the war, it was not decisive; the conflict continued for another sixteen years, and there were many dark days ahead for the English. Indeed, the subsequent period of attrition, in which neither side was able to deliver a knockout blow, is far from glamorous and is shot through with perverse twists of fate.

Although the Spaniards were shocked at the defeat of their great fleet, they went to great lengths to aid the sick, wounded and starving who came off the returning remnant, and almost immediately set about rebuilding their navy. On the other hand, Elizabeth and her council cared little for their victorious sailors and left them languishing in port to die of disease to save money. Elizabeth’s aim remained simple: to defend her territories, to distract the enemy abroad and, when possible, to descend on him in force. Philip dissipated his efforts, particularly by diverting his naval and military resources to assist the Catholic side in the French civil war in the hope of preventing a Protestant take-over and, even more ambitiously, of putting a Spanish infanta on the French throne. For Elizabeth this was a convenient proxy war in which she subsidised the Protestant claimant, Henry of Navarre, and only intervened seriously to prevent the establishment of a Spanish base in Brittany that might have been used as a springboard to invade England. From time to time she let her war party off the leash to attack Spain itself. These large counter-armadas had only variable success because of the divergent aims of the commanders, investors (Elizabeth’s ventures were partly privatised) and Dutch allies. In 1589 Drake failed in his mission to destroy the reconstructed Armada; instead, he wasted his time attempting to take La Coruña and then trying farcically to set up Dom Antonio, the Portuguese pretender, in Lisbon. Essex had more success at Cadiz in 1596, but his ‘Islands voyage’ to capture the returning American treasure fleet by hiding in the Azores proved pointless. Elizabethan foreign policy in these years has been studied by R. B. Wernham in After the Armada (Oxford, 1984) and The return of the Armadas (Oxford, 1994), but Wallace MacCaffery’s Elizabeth I: war and politics, 1588–1603 (Princeton, 1994) has more context and analysis.

Proxy war in Ireland

Philip, for his part, was also willing to encourage and finance a proxy war in Ireland in which England suffered disaster after disaster and which was to cost her as much as all her maritime and foreign ventures put together. Yet he did not intervene directly in Ireland to use it as a stepping-stone to England. The 100-strong Armada of 1596, which he prepared to support the Irish Confederates, was diverted at the last minute to Brittany and, sailing late in the year, was severely damaged by storms off Galicia. His Armada of 1597, bound for south-west England, was dispersed by bad weather in Biscay. This erratic and extremely costly strategy has been recently scrutinised by Edward Tenace, ‘A strategy of reaction: the Armadas of 1596 and 1597 and the Spanish struggle for European hegemony’, in English Historical Review (September 2003).

Although Philip made peace in 1598 with Henry of Navarre (who had been crowned king of France after becoming a Catholic four years earlier), his death in the same year brought no let-up in the war with England. Indeed, Philip III was anxious to maintain the Spanish monarchy’s imperial and Catholic mission against a heretic state now isolated and led by an aging, heirless spinster. Yet, like his father, he had many foreign commitments and mounting debts. The defeat of his intervention in Ireland at Kinsale in 1601–2 (see Hiram Morgan (ed.), The Battle of Kinsale (Bray, 2004)) and the death of Elizabeth in the following year paved the way for peace. James VI and I, Elizabeth’s successor, as king of Scotland had never been at war with Spain and he immediately called off hostilities at sea. Besides, glad to see the back of his uppity Presbyterian subjects, he was unwilling to indulge the Calvinist burghers of Holland and Zeeland.

The ensuing peace negotiations are well treated in Paul Allen’s Philip III and the Pax Hispanica, 1598–1621 (New Haven, 2000). James and his ministers were willing to receive gifts and pensions but they did not budge much, least of all on the demand for Catholic toleration that Spain was pushing hard for. The peace treaty of 1604 essentially settled for the status quo ante, with the vexed issue of Spain’s colonial monopoly fudged. The Spanish state was willing to accept this because of a belief that it could win the peace in the long run, not only diplomatically but also militarily. This proved mistaken; the war had helped to shift the economic axis of the world. K. R. Andrews’s Elizabethan privateering (Cambridge, 1966) has long since explained that, whilst Spain’s treasure fleets had been kept safe by convoys, its merchant marine had been devastated by England’s highly effective privatised method of warfare. Consequently, in the following years much of Spain’s maritime trade came to be carried in English and Dutch ships!

Hiram Morgan lectures in history at University College Cork.

Other websites:

http://www.learningcurve.gov.uk/snapshots/snapshot39/snapshot39.htm

http://www.channel4.com/history/microsites/H/history/pirates/armada1.html

http://www.ulstermuseum.org.uk/collections/archaeology_and_world_cultures/armada/Gold_of_the_Girona/

http://www.historylearningsite.co.uk/spanish_armada.html