Two bishops and a football: Ireland and the Balkans in the 1940s and ’50s

Published in 20th-century / Contemporary History, Features, Issue 5 (Sep/Oct 2007), Volume 15

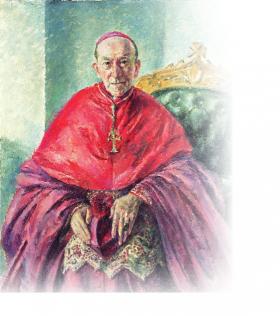

Archbishop of Dublin John Charles McQuaid—at the height of his powers in the 1950s. (National Gallery of Ireland)

In the run-up to the soccer World Cup of 2002 the bust-up between Ireland manager Mick McCarthy and star player Roy Keane in Saipan caused a huge controversy and divided the nation. This was not the first time that the ‘beautiful game’ caused upheaval in Irish society. Back in the 1950s the ‘garrison town game’ set church and state and people at loggerheads with each other.

In 1952 Ireland and Yugoslavia were scheduled to meet in a friendly soccer match in Dalymount Park, Dublin. But one of the most influential and dominant Catholic Church figures in Ireland at the time, Archbishop John Charles McQuaid, had other ideas. McQuaid did not want Ireland to play a ‘Godless country’. He was, like many others, virulently anti-communist. The Cold War was in full spate. Archbishop McQuaid weighed in with his considerable power to get the match stopped. He successfully lobbied the Football Association of Ireland to have the invitation to Yugoslavia withdrawn. FAI officials capitulated very easily. McQuaid had also sent out feelers about his objections to the politicians of the time. The Cold War anti-communist line was an easy sell in the Ireland of the early 1950s. Pupils in national schools around the country prayed for ‘the conversion of Russia’ each day. The match did not take place. McQuaid got his way.

McQuaid at the height of his powers

Archbishop McQuaid was at this time at the height of his powers. In 1944 he reinforced the ban on Catholic students attending Trinity College, Dublin. He saw Trinity as a Protestant university and a threat to the faith of any Catholic students who went there. In 1951 he became embroiled in a battle with the government of the day over what became known as the ‘Mother and Child Scheme’ proposed by Dr Noel Browne, the minister for health. McQuaid wanted to limit the role of the government in hospitals, the majority of which were under Catholic management. The archbishop won because Browne’s political colleagues did not have the courage to stand by him on the issue. McQuaid viewed his ‘victory’ as the most important event in Irish history since Catholic Emancipation in 1829. So hospitals and schools—in fact most aspects of Irish life in the early 1950s—were dominated by Catholic thinking and influence, and Archbishop John Charles McQuaid presided happily over it all.

During the 1950s the Catholic Church maintained a dominant position in the Irish Republic. It had a very strong influence over both politics and ordinary people in Ireland. The bishops were rarely criticised and were usually consulted about government legislation. They ensured that all areas of society adhered to strict Catholic values. In addition, in the 1950s Ireland experienced economic stagnation. There were soaring levels of unemployment and emigration. Not only was Ireland a predominantly Catholic society but, owing to the fact that so many young people emigrated, the population was dominated by an older and more conservative generation.

The Yugoslav background

Croatian Archbishop Aloys Stepinac was placed under house arrest by Tito both for his opposition to the Yugoslav state and his support for the excesses of the pro-Axis Ustase puppet regime during the Second World War.

To fully appreciate why Archbishop McQuaid so vehemently opposed soccer matches between Ireland and Yugoslavia, it is necessary to look at events in the Balkans at that time. After World War I the South Slavs in Baile formed a committee for national unity, which paved the way for the creation of the Yugoslav state. When World War II broke out in 1939 the Yugoslav government declared its neutrality, but in March 1941, under German pressure, they agreed to support Germany. Within Yugoslavia a coup d’état took place and the insurgents formed a government dedicated to neutrality. Germany invaded in April 1941 and the Yugoslav kingdom was broken up. A pro-fascist puppet state headed by nationalists, under Italian protection, was formed in Croatia. For more than two years after the partition of Yugoslavia great political and military turmoil prevailed. Serbian nationalists waged guerrilla warfare against the Croatian puppet state and its protectors. Nationalist Croats under the Ustase regime retaliated by exterminating Serbs. Other guerrilla detachments led by Tito, a Croatian communist, campaigned against the invaders and the Croatian fascists.

In 1941 Tito’s partisans founded a provisional government. Subsequently a new government was established with Marshall Tito as premier and other communists in key positions. On 10 April 1941 Croatia was proclaimed an independent and Roman Catholic state, in which two million Orthodox Serbians lived. Pavelitch, the Croatian leader, planned to expel many of the Serbs from the NDH (the ‘independent’ state of Croatia) and to replace them with Croats and Slovenes from lands annexed by the Germans. He directly ordered the Ustase to conduct a campaign of terror against the Serbs, Jews, Gypsies and communist Croats. Aloys Stepinac, a leading archbishop in Yugoslavia, immediately recognised Pavelitch’s Ustase regime and wrote a letter to his flock, appealing to all to support Pavelitch. Pavelitch and Stepinac were in agreement on the idea of forced conversions to Catholicism. Those people in Croatia and Yugoslavia who refused faced persecution, arrest, concentration camps, or even death. The extent of this campaign reached the proportions of genocide. Pavelitch’s regime was never officially recognised by the Vatican, but at no point did the Catholic Church condemn the genocide and forced conversions to Catholicism perpetrated by the Ustase.

Pavelitch and the Ustase are estimated to have murdered up to 30,000 Jews, 29,000 Gypsies and between 300,000 and 600,000 Serbs. In May 1945 Pavelitch fled to Austria; after a few months he moved on to Rome, where he was hidden by members of the Catholic Church. Six months later Vatican operatives smuggled him into Argentina, where he revived the Ustase movement.

Archbishop Stepinac was placed under house arrest by Tito, both for his opposition to the state of Yugoslavia and for his support for the forced conversions and the excesses carried out by Pavelitch. This house arrest was used by McQuaid to garner support in Ireland for Stepinac, whose support for Pavelitch was ignored. Hubert Butler, who wrote of his own experiences and what he witnessed in the Yugoslavia of that time, was vilified and attacked for his views. Butler tried to alert people to the genocide that was taking place under Pavelitch with Stepinac’s approval, but to no avail. After all, Butler’s voice was that of a Protestant in a Catholic state.

Ireland v. Yugoslavia, round two

The match report in the Irish Times, 20 October 1955. No mention was made of the controversy surrounding the game.

In view of the cancellation of the 1952 match it came as a surprise when the FAI arranged another match with Yugoslavia for Dalymount in October 1955. Archbishop McQuaid was furious that his power had been undermined and that the FAI had not sought his permission before they arranged the match. He wanted the match to be cancelled as a protest against the persecution of Stepinac by Marshall Tito’s communist regime. The trial of Stepinac and the struggle between the Catholic Church and the Yugoslav government sparked widespread interest in Ireland. The FAI was accused of entertaining the ‘tools of Tito in the capital city of Catholic Ireland’. The Yugoslav team were branded as the puppets of a communist state and representatives of a ‘tyrannical regime of persecution’. Schoolboys were warned not to go to the match as it was seen as a mortal sin. On 15 October McQuaid called on the Irish people to boycott the match. The archbishop did not seem to be observing the teaching of Pope Pius XII that politics should not interfere with sports. Nevertheless, on the evening of Wednesday 19 October between 21,400 and 22,000 supporters turned out at Dalymount Park to see the match.

Liam Touhy was the youngest player on the team on the day. He remembers that there was ‘a bit of a fuss’ about it. But for him it was an international, he was playing for his country, and he did not care about the other things that were going on. He did not think that the players in the dressing room knew or talked about McQuaid and the boycott. ‘To us it was a match to be played for our country.’

I sent a letter to the Evening Herald asking for the views of anybody who was at the match. I got replies from two people who attended with their fathers. The perspectives they gave on it now, as adults, were quite interesting. One was understanding of McQuaid’s anti-communist position, in the context of the time, while the other was quite the opposite and ridiculed the role of the archbishop. Philip Green, as a Catholic, refused to do the match commentary. The government and the president did not know whether they could or should attend the game. A group of writers and artists, including Paddy Kavanagh, who we now know often received financial assistance from McQuaid, led a protest by publicly attending the game. Dalymount was full. Ireland lost 4–1. McQuaid lost. The boycott was ignored. Afterwards the FAI was praised in certain quarters for showing ‘much daring’ against the might of the Catholic Church. This was one of the first times in recent Irish history that Irish people, in a very public way, went against the Catholic Church’s directives. Roy Keane’s departure from Saipan pales in comparison to the events surrounding the international in October 1955.

Lynda Slattery was a student in Scoil Airgeal, Ballyhale, Co. Kilkenny, and winner in the senior category of the 2007 Schools’ Prize in History.

Further reading:

N. Browne, Against the tide (Dublin, 1986).

H. Butler, Escape from the anthill (Mullingar, 1985).

J. Cooney, John Charles McQuaid, ruler of Catholic Ireland (Dublin, 1999).