TV eye : A lost son

Published in 20th-century / Contemporary History, General, Issue 2 (March/April 2013), Reviews, Revolutionary Period 1912-23, Volume 21

Michael McDowell on the slopes of Benbulben, Co. Sligo—a compelling presenter in this well-crafted documentary. (RTÉ Stills Library)

Ireland has yet to come to terms with its Civil War, fought over the bitterly divisive Treaty signed in December 1921, resulting in up to 1,000 fatalities and the subject of limited scholarly study. Michael McDowell SC, former attorney general, minister for justice and tánaiste, is a compelling presenter in this well-crafted documentary. He embarks on a journey retracing the steps of Brian MacNeill, his IRA uncle whom he never knew, who was controversially killed in 1922.

Brian, 22, was the second-eldest son of the distinguished academic Eoin MacNeill, leader of the Irish Volunteers who countermanded the 1916 Rising. A gifted UCD medical student, Brian was an IRA GHQ organiser dispatched to County Sligo after the Truce and elevated to senior divisional adjutant rank; he later sided with the anti-Treaty local guerrillas. His two brothers joined the pro-Treaty National Army and his father was appointed Provisional Government minister for education in the fledgling Free State. Despite their political differences, relations remained cordial in the close-knit family, Brian being his mother’s favourite ‘fair-haired boy’.

The documentary investigates the murky killings of Brian and his three IRA comrades, Brigadier Seamus Devins, Lieutenant Patrick Carroll and Volunteer Joseph Banks, on Benbulben’s foggy slopes on the morning of 20 September 1922. The research lacks rigour and nuance, omitting significant details. Considering the substantial budget, it is disconcerting that no consultant historian was listed in the credits. So, too, is the continued excessive dependence on journalists for RTÉ’s historical-themed documentaries.

Eoin MacNeill, Brian’s father—Provisional Government minister for education in the fledgling Free State. Despite their political differences, relations remained cordial in the close-knit family, Brian being his mother’s favourite ‘fair-haired boy’. (UCD Archives)

In an unfounded observation, McDowell declared that ‘not one coherent [Free State] account has ever been given as to what happened’. In fact, an unnamed National Army soldier gave a detailed account to Republicans. This overlooked key source (Bureau of Military History Contemporary Documents 333/36, Military Archives) reveals how the IRA unit were lured to their deaths by a ruse. Five of the six named killers were County Longford natives. The main culprit, Captain McGoohan, masqueraded as an IRA member wearing a civilian cap and went ahead of his 56 troops to signal to the four IRA men to join him. Led into a trap, the IRA unit was then surprised, ordered to surrender, disarmed and identified. McGoohan and another officer decided to shoot their prisoners. Most of the troops refused to volunteer for a firing squad. McGoohan told them that ‘It did not matter as he had a Lewis gun that would do the work’. He and another officer, along with four soldiers (who were British Army ex-servicemen), were responsible for the cold-blooded killings.

Later that morning, the same ruse was employed to capture two IRA men a mile from the scene, Captain Harry Benson and Volunteer Thomas Langan. They were also killed after they were taken prisoner, and a bayonet was used to mutilate Langan’s corpse. Sifting through the military reports, McDowell unravels a web of duplicity. He persuasively argues that there was a cover-up by senior officers, who lied and fabricated evidence to conceal a premeditated atrocity. Eoin MacNeill was complicit in the cover-up, clinging to the fantasy of his dying son shaking hands and joking with his captors. McDowell concludes that the killers were acting on the orders of Seán MacEoin, the National Army’s general officer commanding Western Command. In a humiliating blow to MacEoin’s prestige, Brian MacNeill’s IRA unit had previously captured an armoured car in what was the likely motive for the atrocity, and also inflicted several fatalities on their enemy.

McDowell’s antipathy for the anti-Treatyites colours an otherwise insightful narrative. Reserving his moral indignation for the IRA, he provides a rationalising gloss:

‘If you start a civil war and if you declare, for instance, TDs on the other side are people who could be shot on sight, then you can’t expect to be treated as if you’re charged with insider trading or something’.

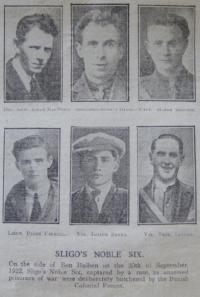

Republican propaganda published in the anti-Treatyite journal Éire featuring ‘Sligo’s Noble Six’—including Brian MacNeill (top left)—who are still commemorated today. National Army atrocities ultimately proved counterproductive, eroding public sympathy and support for the Provisional Government.

His trenchant view is factually incorrect. The Civil War commenced in June 1922 when the National Army, following a British ultimatum, borrowed artillery to bombard the IRA-occupied Four Courts. Five IRA prisoners were officially executed before the IRA chief-of-staff, Liam Lynch, launched systematic retaliation, having warned the Provisional Government to cease shooting Republican prisoners. In November 1922 Lynch ordered 56 members of the ‘Provisional Parliament’, whom he claimed voted for the ‘murder bill’ inaugurating the executions policy, to be shot on sight and their houses destroyed. More TDs died at the hands of the Provisional Government forces than were killed by the IRA. McDowell offers no comment on the slaying of Seamus Devins, 37, married, and an elected TD for Sligo, securing 7,370 first-preference votes in the general election shortly before the Civil War outbreak. Another constituency colleague, Dr Francis Ferran TD, died in the Curragh internment camp in 1923.

The documentary ignores the wider deadly ramifications of the high-profile atrocity. There was a chilling ambivalence towards excesses by a government professing to uphold law and order while permitting troops to flout it. Turning a blind eye to the harrowing misdeeds at Benbulben, where the son of a minister and an elected TD were callously cut down by machine-gun fire while prisoners, ensured that worse atrocities would follow, with soldiers knowing they would not face punishment. There were striking parallels to the later grisly atrocities in Kerry involving soldiers from outside the region, a subsequent whitewash enquiry but also courageous officers prepared to reveal the sordid truth. National Army depredations far surpassed the IRA’s in scale and horror. The anti-Treaty journal Éire listed 106 victims of what can be loosely described as extrajudicial killings committed by government forces from June 1922 to August 1923.

McDowell maintains that anti-Treatyites were ‘peddling snake oil’. This does not explain why Republicans gained almost 290,000 first-preference votes in the general election in 1923. De Valera topped the poll in County Clare (as did the new IRA chief-of-staff, Frank Aiken, in County Louth), gaining more than double Eoin MacNeill’s voter share in the same constituency. This illuminating documentary will hopefully encourage historians to delve into other unsavoury Civil War killings. HI