Titanic: sinking in a sea of hype?

Published in 20th-century / Contemporary History, Issue 3 (May/June 2012), Platform, Volume 20

Titanic Belfast under construction in July 2011—the £90m signature building, which houses the Titanic museum, unfortunately bears a strong resemblance to an iceberg.

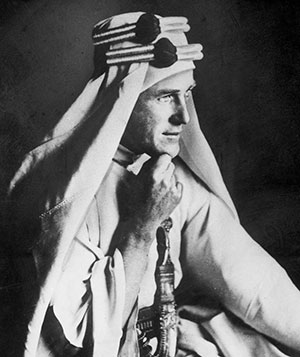

‘When the legend becomes fact, print the legend’, was the advice given by the crusty old editor in the John Ford western The man who shot Liberty Valence. To a historian it may seem that this is the guiding principle behind the celebrations of the Titanic, history’s most successful disaster. The outline of its story is well known, but most of what the general public ‘know’ is legend or myth. A legend may be viewed as something that has grown through word of mouth, cultural output or popular media. On the other hand, a myth may be said to be something that is manufactured in a platonic way towards a particular end.From the day it was launched the Titanic acquired a legendary status. It was not just its size and opulence that attracted attention but also the ‘unsinkable’ tag. This was seen as a celebration of technological achievement in 1911 when she was launched but was viewed as hubris after she sank. There was a cult around the ship from then on. The circumstances of the sinking, the lives lost, the conflicting stories and the revelations at the board of trade inquiry all contributed to ensuring that, while she may have sunk beneath the Atlantic, the Titanic would never go away.From 1912 onwards the cultural output covered the whole spectrum from novels, poetry and plays to painting, music and opera. Mention of the name alone conveyed a whole raft of ideas about life, death and Western civilisation, from Noel Coward’s 1933 Cavalcade to the 1970s TV soap Upstairs, downstairs. But two films in particular raised the profile of the doomed vessel for two different generations. A night to remember in 1958 was a documentary-style film with an all-star British cast, which ensured that the Titanic was prominent in the post-war public’s imagination. The ship had probably sunk back into the obscurity of hardcore devotees when it was again thrust into the public eye by James Cameron’s 1997 film. This $200 million epic uses the sinking of the ship as the background to (and allegory for) a doomed love story. Unlike the 1958 film, Cameron’s is not strictly historical and takes liberties with the actual events, not to mention the realities of Edwardian society. Nevertheless, it was hugely successful worldwide and became (even for those who had not seen it) the ‘true’ story.This is not to say that the ship was forgotten in its hometown, but attitudes in Belfast were always contradictory. Pride in the achievement was tempered by its sinking with huge loss of life. An oral tradition survived in the city and many families could claim some connection to the building of the Titanic. It must be admitted, however, that this was largely confined to the Protestant community. I grew up in north Belfast and the Titanic was not viewed as part of our heritage. As a child, I heard the usual apocryphal stories about its having bad luck because anti-Catholic slogans were scrawled on its plates, and that a Catholic apprentice who had accidentally been sealed into the ship was left there despite calling for help and banging on the hull.

The Titanic had probably sunk back into the obscurity of hardcore devotees when it was again thrust into the public eye by James Cameron’s 1997 film. (Paramount Pictures)

The renewed interest in the wake of the Hollywood epic came at an opportune moment for Belfast. Soon after, the Good Friday Agreement had been signed and the city was marketed as being ‘open for business’. The upsurge of interest was a godsend. Even though Belfast did not feature in the film or surrounding publicity, the city went out of its way to remind people that this is where the Titanic had its origins.This is when the myth-making began. The actual fate of the ship was underplayed in favour of a celebration of the technological achievement and the city that built it. Since 1997 there has been a concerted effort by the authorities to market Belfast as the ‘Titanic city’. Bus, walking and boat tours take visitors to the shipyards; posters, models, T-shirts, caps and the other paraphernalia of the souvenir industry are sold in the city’s shops and tourist offices. When the decision was made to pump millions into civic regeneration, the now defunct shipyard district was chosen and rebranded as ‘the Titanic Quarter’. Unfortunately, its £90m signature building, Titanic Belfast, which houses the Titanic museum, bears a strong resemblance to an iceberg.Unlike the iceberg, the 100th anniversary was seen from a long way out and was prepared for. There has been a stream of books, events, press releases, festivals and so on, not just commemorating the ship but also celebrating it as something that all Belfast people can be proud of. A myth is being promoted that excludes any ambivalent attitude towards the Titanic and any negative connotations associated with it. Most of what has been written, said or broadcast cannot be accused of falsehood, but at the same time it is guilty of the sin of omission, of being economical with the truth. Part of the legend was always ambiguous, given that the Titanic did not live up to its arrogant boast and almost 1,500 people died when it went down.Part of the reality was that Belfast in 1912 was not a happy place where Catholic and Protestant, rich and poor, all united in cheering the ship as she slipped out of the dry dock into Belfast Lough. Indeed, the huge crowds gathered to see the launch sang Rule Britannia over and over. There is no room in the myth for the broader historical context. Left out are the tensions over Home Rule, the one-sided nature of employment at Harland & Wolff, and the sectarian violence not just in Belfast but in the shipyard itself. In 1912 Catholics and ‘Rotten Prods’ (trade unionists and Home Rulers) were expelled en masse from the shipyards. Nor is there mention of the dangerous nature of the work, the lack of basic health and safety, and the industrial disputes that characterised Belfast for much of the early twentieth century. For example, last year Channel 4 produced a series that concentrated largely on the technological aspects and portrayed the ship as an achievement for the whole community to be proud of. Coming soon is a major television series about the Titanic written by Julian Fellowes, the man behind Downton Abbey, which incidentally had one of its characters go down with the ship.Of course, we could take the view that Belfast should be congratulated for making the best of the opportunity it has been given. Economic imperatives dictate that a simple story to attract investment and visitors is more important than historical or cultural integrity. Other places, too, are trying to cash in on their connection with the doomed liner. But there is something more going on with the promotion of the Titanic. We all know about PC—political correctness—but is there not here in Ireland also PPC, peace process correctness? Under PPC we are all supposed to foster what binds us together and avoid unpleasant truths about the present as much as about the past. And the great ship is promoted as just that: a uniting myth that transcends political and sectarian divisions.

‘When the legend becomes fact, print the legend.’ (New York American, Tuesday 16 April 1912)

This can clearly be seen in the ‘Titanic: built in Belfast’ section of the Discover Northern Ireland website. This advertises exhibitions and museums that promote the Titanic’s ‘honour and glory’ and celebrate the ‘affluence and optimism’ of Belfast in 1912. The signature building will house nine exhibitions with titles like ‘Boomtown Belfast’, which concentrate on the building of the ship, the disaster and its fame. One gallery will look at ‘myths and legends’ but mainly in the international context. Historians and publishers have willingly fallen into line, producing a plethora of books in the same vein.The commercial exploitation—for example, it costs £13.50 to get into Titanic Belfast—promises to bring jobs through the tens of thousands who will visit the Titanic’s birthplace, and so justify the millions spent on the Titanic Quarter. At the same time, however, a myth is being fostered that the Titanic was something that united the people of Belfast and represents a shared heritage that both sides of the community can celebrate. In the name of bedding down peace, historical realities and their complexities are shunted to one side in favour of promoting a cosy view of the past. In all of this, is there not a danger that the real Titanic is being lost? HI