‘The South is in the mood for violence’: Bloody Sunday, 1972

Published in 20th-century / Contemporary History, Features, Issue 1(Jan/Feb 2012), Volume 20

Fr Edward Daly leads a group carrying fatally wounded Jackie Duddy. Initial disbelief turned to anger as details of the massacre in Derry reached southern homes by teatime on Sunday 30 January 1972. (Stanley Matchett)

Walkouts and impromptu protest marches

But on Monday morning walkouts took place at factories in the Shannon industrial estate and on Cork docks. By lunchtime thousands of workers in Shannon, Limerick, Cork, Galway, Dundalk and Waterford had struck and joined impromptu protest marches. In Cork city, ‘so many marches were taking place that at times columns of protesting workers passed each other in the streets going in opposite directions’. Protesters converged on Cork city hall, where they were met by the lord mayor, who was widely quoted as telling the cheering marchers that ‘if they want murder, they’ll have murder—one of theirs will go for each of ours’. In Dublin a natural focal point for protest was the British embassy at 39 Merrion Square. Throughout the day, ‘workers, students and schoolboys . . . socialists, Republicans and people of no particular group’ converged on the building.  A report in the Connaught Tribune conveyed the mood:

A report in the Connaught Tribune conveyed the mood:

‘In O’Connell Street and Merrion Square . . . hundreds of people offered the Sinn Féin and IRA organisations whatever help they could. It was an emotional scene as people queued to have their names taken, committing themselves to whatever task the militant republican organisations gave them . . . they abandoned their offices, shops, and factories and took to the streets . . . not since the hectic general election period of the thirties were so many militants on the streets demanding drastic action.’

In early evening, following an Official Sinn Féin rally during which it was announced that ‘notice to quit’ was being served, petrol bombs and flares were thrown at the embassy. Later that night a Provisional Sinn Féin march arrived and there was another attempt to storm the building, but Gardaí successfully dispersed the crowd after baton charges.

Irish ambassador withdrawn from London

By Tuesday the government had withdrawn the Irish ambassador from London and announced that Wednesday 2 February, when the funerals of eleven of the victims were to take place in Derry, would be a national day of mourning. All schools were to close and RTÉ would provide live coverage of the funeral services. The majority of trade unions asked their members to take between one and three hours off work to attend memorial events and employers’ organisations agreed to facilitate this. Many also agreed to donate wages to a fund for the Derry victims. Some businesses announced that they would close for the entire day. The Irish Farmers Association also called for its members to cease work for at least an hour on Wednesday. Protests continued on Tuesday itself, however, with 10,000 people marching in Sligo and rallies in Tralee, Wexford, Dungarvan, Maynooth and Ballyshannon. Over 150 local women, described as ‘Foxrock housewives’, marched on the British ambassador’s residence in Sandyford. Airport workers refused to service British aircraft or to unload their cargo. Dockers blacked British shipping, and in Galway they boarded a British vessel and forced it to take down its ensign. Bus workers in Cork announced that they would strike for 24 hours on the national day of mourning. In Dublin, protests continued at the embassy. An explosion destroyed the building’s armoured door, while over 70 petrol bombs were thrown at its reinforced windows. After several hours of clashes, with injuries on both sides, the Gardaí prevented further damage taking place. There were, however, other arson attacks on British-owned businesses, mainly in Dublin.On Wednesday 2 February the state came to a standstill. In spite of fierce wind and driving rain, marches and memorial services took place in almost every town and village. The description of the scene in Ardee, Co. Louth, where 5,000 marched, was typical—there were

‘. . . duffle coated, rain soaked clergy, nuns in black headscarves, youths wearing black berets, Ardee ITGWU, Ardee Order of Malta, Ardee Band, Ardee Bread Co., businessmen, men in green berets, children in duffles and little girls wearing plastic rainhats and bewildered looks, old men, old women moving their lips slowly . . . one Garda marching in plain-clothes, another on duty eyeing up the crowd, his collar turned up against the rain.’

In most areas a Requiem Mass was celebrated before or after the protest rally. In many places Protestant memorial services also took place. The rally platforms typically included politicians from all parties, clergy and trade unionists. Members of the IRA (Provisional and Official) appeared at several demonstrations, sometimes carrying arms. In all areas black flags were displayed, black coffins bearing the number ‘13’ carried, and Union flags and effigies of British prime minister Edward Heath burnt.

Many politicians and local councillors travelled to Derry for the funerals, but Taoiseach Jack Lynch and most of the Fianna Fáil cabinet attended a memorial service in Dublin’s Pro-Cathedral. (RTÉ Stills Library)

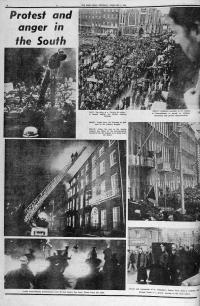

British embassy ablaze

Many politicians and local councillors travelled to Derry for the funerals, but Taoiseach Jack Lynch and most of the Fianna Fáil cabinet attended a memorial service in Dublin’s Pro-Cathedral. The táiniste, Erskine Childers, took part in a similar service in St Patrick’s Cathedral, while Dublin’s Methodist, Presbyterian and Jewish places of worship all marked the day with special ceremonies. Many people in Dublin attended early morning Mass before making their way to the city centre. Thousands had taken the entire day off work. Some went directly to the embassy, where protesters had gathered well before noon ‘waiting for something to happen’. Others joined the Dublin Council of Trade Unions march from Parnell Square. There were perhaps 100,000 people in the city centre by afternoon, with observers noting both ‘sadness and apprehension’ and ‘a hint of anarchy in the air’ amid the ‘closed shops, bars, restaurants, theatres . . . and boarded over frontage of British firms’. At first the protest was peaceful, with women telephonists kneeling on the embassy steps and saying the rosary, while ‘most people, including the Gardaí, joined in’. Then, to the sound of the muffled drums of the Irish Transport Union band, marchers began to arrive. There was soon a ‘mighty crush’ in Merrion Square, with people climbing trees or hanging onto lampposts overlooking the embassy. Railings were torn up and crowds spilled into the park. By 4pm petrol bombs were being thrown, encouraged by the crowd, who cheered when a bomb hit its target, ‘almost as if they were at Croke Park’. Then at least three men scaled across balconies, making their way slowly to the embassy. With the ‘deftness of a cat burglar’, one raised the tricolour to half-mast on the embassy flagpole. Then hatchets were used to smash the upper windows. To cheers and the sound of ‘For he’s a jolly good fellow’ petrol bombs were thrown through the broken windows. By 7pm the embassy was ablaze. Fire engines were prevented from reaching the area. Ambulances were allowed through, however, as both Gardaí and members of the crowd had been injured. Thousands stayed to watch the embassy burn, but after attacks began on the nearby British passport office the Gardaí started to regain control, carrying out several baton charges. Cars were overturned and dozens of windows smashed in Grafton Street before order was restored in the early hours of Thursday morning. There were smaller-scale protests over the following days, but nothing on the scale of earlier in the week. On Sunday 6 February, however, perhaps as many as 15,000 people from the Republic travelled to Newry to take part in what was to be the last great civil rights march, of around 40,000 people.

Fears that the violence was ‘coming down here’

In the immediate aftermath of Bloody Sunday the sentiments of the Sligo Champion were echoed by many commentators: ‘the South is in the mood for violence . . . there is a growing feeling that the only language Britain understands is through a gun barrel’. After the destruction of the embassy, however, the tone began to change. There was widespread condemnation of arson attacks on British property and of threats against both British citizens living in Ireland and Irish Protestants. The Irish Press warned that ‘this is not a time to fritter away our energies and resources in internal savagery and disorder’, and asserted that, while ‘the embassy burning was serious enough, what followed was appalling’. Jack Lynch warned that a ‘small minority of men’ were trying to use anger at Britain to overthrow the southern state. Others warned of the damage being done to an already ailing tourist industry and raised fears of British businesses fleeing the Republic. The Fianna Fáil Ard Fheis, held in late February, was notable for the lack of anti-British rhetoric. Some thought that Bloody Sunday had created a ‘completely new atmosphere . . . after two and a half years of apathetic detachment, the emotions of the South have at last spilt over’. By mid-1972, however, others were discerning a change in mood. Fears that the violence was ‘coming down here’ were prevalent, as was growing indifference and even hostility to Northern nationalists. How and why this occurred remains for historians to explore and explain, but what is certain is that no event north of the border was ever again to have the same impact on popular mobilisation in the south as Bloody Sunday. HI

Brian Hanley is a research fellow at the Institute of Irish Studies, Liverpool.

Further reading:

A. Craig, Crisis of confidence: Anglo-Irish relations in the early Troubles, 1966–1974 (Dublin, 2010).D. Ferriter, The transformation of Ireland, 1900–2000 (London, 2004). B. Hanley & S. Millar, The lost revolution: the story of the Official IRA and the Workers’ Party (Dublin, 2009). D. Keogh, Jack Lynch: a biography (Dublin, 2008).