Seán McLoughlin – the boy commandant of 1916

Published in 20th-century / Contemporary History, Features, Issue 2 (Mar/Apr 2006), Revolutionary Period 1912-23, Volume 14

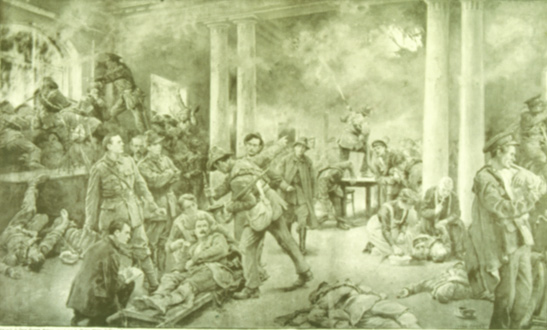

Paget’s Scene in the General Post Office, Dublin, just before its evacuation, Easter Week, 1916. (National Museum of Ireland)

Seán McLoughlin was born in Dublin on 2 June 1895, the second child of six eventually born to ITGWU activist Patrick McLoughlin and his wife Christina. Involvement in Irish nationalist activity began early. Aged fifteen, McLoughlin joined both the Gaelic League and Fianna Éireann. Like many Fianna members, he became involved in the Irish Republican Brotherhood (IRB) but was also influenced in a socialist direction by the Dublin Lockout, in which his father was involved. In November 1913 McLoughlin joined the Volunteers; after the split that followed John Redmond’s support for the British war effort, he went with the minority Irish Volunteers and became a lieutenant in G company. Seán Heuston was captain. The early months of 1916 saw both men take their respective ranks with them into D company, and it was as part of this unit that they would see action during the Easter Rising.

Mendicity Institution

On Easter Monday morning, Heuston, McLoughlin and the rest of D company were dispatched to the Mendicity Institution on the quays. Their orders were to effect a takeover and use it to hold in check British troops stationed at the adjacent Royal Barracks. This would provide time for the main contingents in the Four Courts and GPO to establish their positions. It was expected that D company would be able to hold the Mendicity for only three or four hours, but in the event they remained there for 50 hours before the British forced a surrender. During these two days McLoughlin made several trips across quite hazardous terrain to the GPO, in order to obtain supplies and to brief the leadership on developments. On Wednesday, he was returning to the Mendicity when the final British attack opened up on it. McLoughlin was close to Queen Street Bridge when this occurred and was almost arrested. Some local people pointed him out as a Volunteer to a nearby party of British troops, forcing him to turn on his heels and flee to Church Street. He spent the night at the Four Courts garrison, taking command at the Chancery Place end, before returning to the GPO.

It was in the GPO on the Thursday of Easter Week that McLoughlin’s rise to prominence began. The HQ was under heavy fire at this stage. British troops were maintaining a continuous barrage on three sides of the GPO. In addition, the heavy artillery bombardment that had begun the previous day had intensified and was destroying buildings throughout Sackville Street (O’Connell Street). James Connolly, aware that the GPO was being surrounded and concerned that the British might be crossing from the quays up through Liffey Street, sectioned off 30 men and placed them under McLoughlin’s command. Connolly had been hugely impressed by McLoughlin’s conduct all week and had no qualms about placing him in a more responsible position. McLoughlin’s orders were to take over the offices of the Independent and from that vantage point stem any movement of British troops from the south side of the Liffey. The offices were quickly commandeered, and a watch was posted throughout the night. During the night, McLoughlin clambered onto the roof of the building and was awestruck at the spectacle that met his eyes. The whole Sackville Street area, it seemed, was a raging inferno. The Dublin Bread Company building, Reis stores, Hoyte’s oil works, Clery’s, the Imperial Hotel and many other buildings were being swallowed whole by the blaze. McLoughlin feared that Republican hopes of victory were being similarly consumed:

‘In front was a roaring sea of flame, leaping to the sky, with the crackle of musketry and cannon-pealing the accompani-ment. Behind was another terrific blaze from the Linen Hall Barracks, which had also gone up. It was apparent now we were doomed. No stories of “landing Germans” would now be believed. It was a handful of daring men facing the wrath of a mighty Empire, with the odds on the Empire.’

On Friday morning McLoughlin returned to the GPO, where he was informed about Connolly’s injuries. These had occurred the previous day when, stepping out into a laneway to observe McLoughlin’s unit take the Independent, Connolly’s leg and ankle were shattered by ricocheting shrapnel.

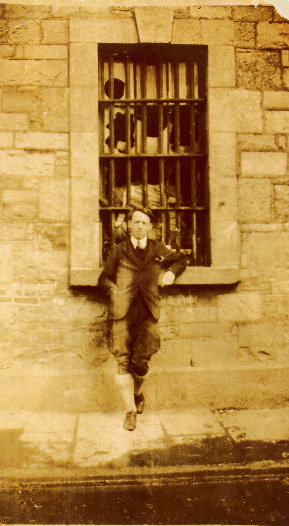

McLaughlin outside the GPO after his release from Frongoch in December 1916.

He was confined to a stretcher as a result. The situation soon got worse. About mid-day, the British shelling recommenced and direct hits were scored on the GPO. The building was soon ablaze and the Republican leaders were forced to plan an evacuation. McLoughlin was discussing this with Seán MacDiarmada when they were informed by another Volunteer that the O’Rahilly had left the GPO with a contingent of men in order to set up a new HQ at the Williams and Woods soap and sweet factory in Great Britain Street (Parnell Street). McLoughlin knew from his earlier travels that the whole of this street, including Williams and Woods, was in the hands of the British and had favoured instead a retreat down Henry Street. Realising that the O’Rahilly faced certain death, he rushed out of the GPO to bring him back, but was too late. By the time McLoughlin reached Moore Lane, the Sherwood Foresters had cut down the O’Rahilly and 21 of his unit.

McLoughlin takes command

McLoughlin takes command

It was in this deteriorating situation that McLoughlin took control. Turning back from Henry Street towards the GPO, he could only look on as the GPO garrison finally began to evacuate and came running in his direction. The scene was chaotic.

‘I turned back towards the GPO and saw the whole garrison coming towards me at the run. There was terrible confusion—almost panic. Somebody shouted that they were being fired on from the roof of a mineral water factory. I detailed a number of men to break the door down. Another party entered from the opposite door and they opened fire on each other—one man was killed and several injured. I was incensed with rage, calling “have you all gone mad, what the hell is wrong!” and I drove them to the wall, threatening them.’

Order was disappearing fast. Many Volunteers had run from the GPO straight to Moore Street, where they were cut to pieces by the heavy machine-gun fire of the British troops stationed at the Great Britain Street end. McLoughlin diverted the fleeing masses (including the provisional government leaders) up Henry Place, where some order was restored. MacDiarmada spoke to McLoughlin and expressed his fears that all seemed lost. ‘My God’, he exclaimed, ‘we are not going to be caught like rats and killed without a chance to fight.’

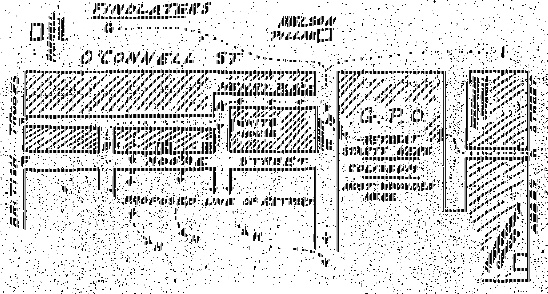

McLaughlin’s hand-drawn map of the evacuation (Camillian Post, 1948)

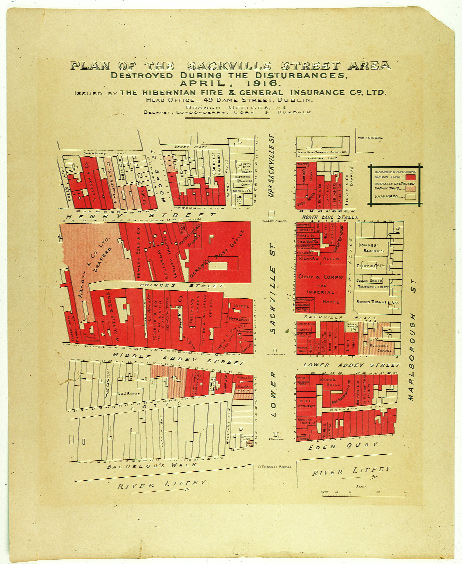

insurance map.

McLoughlin attempted to reassure MacDiarmada. ‘There is no need to panic’, he said, ‘I can get you out of here, but there will be only one man giving the orders and I will give them.’ With Connolly’s approval, this was agreed and control was passed to McLoughlin. McLoughlin knew the position to be desperate, but felt that if they could get past Henry Place, and the Moore Lane opening, they might be able to take refuge in the tenements of Moore Street. He instructed Volunteers to search for material for a barricade behind which this manoeuvre could be attempted. A motor-van was pulled from a nearby factory yard and pushed across the mouth of Moore Lane. It partially screened the Volunteers from the British line of fire at the end of the lane, giving them the chance to dash across the opening and into the Moore Street tenements. The chaos here was again acute. Many Volunteers, unnerved at the ferocity of the British attack and the sight of their comrades being hit, hid in Henry Place, almost frozen with fear. According to one source, McLoughlin ‘stood out like a rock’ amidst this confusion, and was now the only man whose orders were being listened to.

Over 300 Volunteers eventually made it into Moore Street. Headquarters were established in a corner-shop. The British were encamped at the bottom of the street, but for now made no attempt to mount an offensive. ‘I had the feeling’, McLoughlin explained later, ‘that the British were surprised by the unexpectedly large body of men and that our immunity, strange as it may seem, lay therein, at least for the time being.’

Moore Street retreat

On Friday evening HQ staff—including Pearse, Connolly, MacDiarmada, Clarke, Plunkett and Harry Boland—met. MacDiarmada proposed that McLoughlin be given the military command. Connolly seconded this and insisted that McLoughlin hold his rank of commandant-general. McLoughlin’s main task was to devise a retreat plan from Moore Street.

The north side of the GPO along Henry Street. McLaughlin had to lead the evacuating Volunteers across Henry Street to Moore Street, to the extreme left of this picture. (National Museum of Ireland)

It was only a matter of time before the British attacked, so McLoughlin instructed the men to begin burrowing through the connecting walls of the Moore Street tenements, in order to diffuse their forces as widely as possible. He considered any movement of men from an enclosed space to be a ‘gift to the enemy’ and felt that spreading their forces in this fashion was the only way to offset this danger. McLoughlin insisted that the men continue this work through the night, in relays, and appointed officers to oversee it.

By daybreak the burrowing had reached Sackville Lane (now O’Rahilly Parade), which was close to the British barricades. The British appeared unaware of this. McLoughlin now felt that it was time for the breakout and presented HQ with his plan. He proposed an attack on the British barricades from Sackville Lane, carried out by a ‘death or glory’ squad of 20 to 30 men. This would be a diversionary assault, allowing the main garrison, now spread throughout the Moore Street tenements, to break out and run towards a large warehouse in Henry Street. Here, forces would be reassembled and would move down past Capel Street, on to the Four Courts, where they would link up with Ned Daly’s garrison and ‘fight it out with the British there’. Pearse was unsure about the plan. He had observed civilians being shot in Moore Street and was worried about the potential for more such deaths if such a mass retreat took place. ‘I am sorry, I cannot help that’, replied McLoughlin firmly, ‘this is a military operation and I can only make it successful if I don’t think about such things.’ Pearse seemed to accept this point, and the plan was ratified by all of the provisional government leaders. McLoughlin set twelve o’clock mid-day as zero hour and began recruiting for the ‘death or glory’ squad. Seamus Robinson, later a leftist IRA commandant in County Tipperary, volunteered for this squad and remembered McLoughlin, with a yellow band on his tunic signifying his high rank, organising it.

Surrender

McLoughlin moved his squad out into Sackville Lane and gave each man his instructions. As he was in the middle of these preparations, however, he was approached by MacDiarmada and told to return to HQ, which was now based in Hanlon’s fish shop at 16 Moore Street. Back at HQ, Pearse was still troubled about the potential for civilian casualties and instructed McLoughlin to delay his attack for one hour, pending further consideration. When McLoughlin returned to Pearse again, he was told that the Rising was over. ‘I am sending a message to the British to end this fight’, Pearse informed McLoughlin flatly.

McLoughlin was unhappy about this decision and did not take the news well. But Tom Clarke spoke to him, telling him that he had done his best, whilst Connolly, who knew that he himself would soon be facing a firing squad, urged McLoughlin to look to the future:

‘Connolly beckoned to me from the bed and said “you must not take it so hardly; you are young, you will see a lot more struggles before you die . . . you must keep quiet about the part you played. You will still be needed. You will have plenty to do in the future, if you keep quiet . . . we have done our best; it was better than we hoped. It has not ended as it might have, in disaster”.’

Pearse went to the British HQ to seek terms for the ending of hostilities. He was then taken into custody. A message was sent back to Moore Street by the British, ordering the Volunteers to lay down their arms and march behind an advance party, bearing white flags, to Findlater’s grocery store on Sackville Street. McLoughlin lined the garrison up in the yard behind Hanlon’s and told them of the terms. However, despite British instructions to the contrary, McLoughlin insisted that the Volunteers march to the place of surrender with their unloaded rifles in hand.

Patrick Pearse surrenders to General Lowe. (National Museum of Ireland)

For one participant, Joe Good, McLoughlin’s insistence here allowed Republicans to end hostilities in a dignified and honourable fashion rather than being humiliated, marching with their hands on their heads. After a verbal spat with British General Lowe—who was seething, both at the sight of McLoughlin issuing orders to the Volunteer columns at Findlater’s and at the fact that they had carried their arms—the surrender was eventually taken.

From Findlater’s, the Volunteers were taken to the gardens in front of the Rotunda hospital, where they sat until the following morning. They were then marched through the ruins of Sackville Street to Richmond Barracks in Inchicore, where they were searched and interrogated by police and military intelligence officers. Thanks to the fact that the Dublin detectives regarded him as a junior and relatively insignificant figure in the Volunteer movement and the curious actions of a British captain, who removed McLoughlin’s commandant tabs before he was inspected by those detectives, McLoughlin escaped the fate of seven of the eight other commandants. It would be a prison cell for him, rather than a firing squad.

McLoughlin was sent first to Knutsford jail and then to Frongoch internment camp. He was released in December 1916. It was a release that finally brought to an end one of the Easter Rising’s most remarkable stories. McLoughlin was not yet 21 when the Rising occurred and could scarcely have believed that by the end of Easter Week he would be commandant-general of the army of the Irish Republic. By general consensus, however, all through that week McLoughlin displayed leadership qualities rare in one so young and an ability to think logically and act decisively in the most disorientating and chaotic of circumstances. His promotion to the head of military command was testament to these special qualities and shows that McLoughlin, not de Valera, was the highest-ranking of the 1916 survivors.

Epilogue

Seán McLoughlin was a prominent activist in the Irish Republican and Irish and British communist movements throughout the period 1917–24. In 1924 he moved to Hartlepool and later lived a quiet life with his wife and two children in Sheffield. On 13 February 1960, McLoughlin died in Sheffield Royal Infirmary from heart failure and hypertension. It was a death that passed unnoticed in Ireland. There was no mention of McLoughlin’s passing in any newspaper, nor representation from any Irish nationalist, republican or socialist organisation at his cremation, which took place four days later. It would appear that, long before his untimely death, Seán McLoughlin, the boy commandant of 1916 and military leader of men among the most celebrated and commemorated in Irish history, had himself become Ireland’s forgotten revolutionary.

Charlie McGuire is a postgraduate history student at NUI, Galway.

Further reading:

M. Caulfield, The Easter Rebellion (Dublin, 1995).

R. Challinor, The origins of British Bolshevism (London, 1977).

S. McLoughlin, Statement to the Bureau of Military History, National Archives, Ireland, WS 290.

E. O’Connor, Reds and the Green (Dublin, 2004).