Mythologising a movement: Northern Ireland’s ’68

Published in 20th Century Social Perspectives, 20th-century / Contemporary History, Features, Issue 5 (Sep/Oct 2008), Northern Ireland 1920 - present, Volume 16

Young people assembled on Guildhall Square to protest after 5 October 1968. Only 400 or so people had taken part that day; when the march was restaged a month later, almost 40 times that number participated.

Is not the pastness of the past,’ asks Thomas Mann in The Magic Mountain, ‘that much more profound, more complete, more legendary, the more immediately it falls before the present?’ The stories told about the civil rights era invite a positive response to this question. Indeed, the mythologising of the movement began as the events themselves were taking place.

Newspaper articles, television interviews, inquiry reports, self-published memoirs, summer schools and general histories have repeated the same claims so many times that the legend has become fact. The creation of a Protestant-dominated state with a sizeable Catholic minority in the aftermath of the First World War is understood to have made conflict inevitable at some point in the future. For decades an uneasy peace largely held, with Unionism kept in power by an unjust system and with Nationalism and Republicanism unable to challenge it.

This, so the story goes, only changed when the first generation of Catholics to benefit from the education reforms of the mid-1940s came of age in the late 1960s. A new middle class with new ideas had emerged to lead the community. Catholics started to protest in the streets for ‘British rights for British citizens’—and were met with police batons in Derry on 5 October 1968. This time, though, the traditional crackdown split the Unionist Party rather than binding it together, led to criticism rather than support from Britain, and brought more people onto the streets instead of crushing the movement.

This legend has lasted so long because it is a compelling story that has been compellingly told: first-hand accounts that fit Northern Irish stereotypes recited by civil rights leaders who went on to political and media careers. Historians have been accomplices to this—however unintentionally—by failing in their duty to replace myth with something messier. The general reluctance to tackle the subject in any depth was partly based on recognition of the moral foundations of the civil rights movement and the absence of important sources. With the closing of the phase of history that began with the civil rights crisis and the opening of archives, however, the Owl of Minerva seems to be spreading its wings.

John Hume: his claim that the Derry Housing Association was refused planning permission in early 1968 to build in a Protestant area because it would upset the gerrymander—and that this showed that change would only come from the street, not through the system—is suspiciously neat. (Pacemaker)

The Little Owl’s hooting gives voice to big unsatisfied thoughts. Nobel Peace Prize winner John Hume’s claim that his Derry Housing Association was refused planning permission in early 1968 to build in a Protestant area because it would upset the gerrymander—and that this showed that change would only come from the street, not through the system—is suspiciously neat. Turning to the primary sources rather than trusting personal testimony reveals divided loyalties and different definitions of reform. When Hume argued his case at a council meeting, the records show that Nationalist councillor James Doherty countered that ‘this matter was not a political issue’. He objected to the proposals as they would have seriously weakened the Londonderry Area Plan. This was an ambitious project to build almost 10,000 homes and attract new industries to the North-West. Stormont had calculated that jobs and houses would pacify the city after the loss of the second university had prompted cross-community protests—and keep Unionism in control. Nevertheless, the Derry Journal was convinced that ‘Not even the most cynical of our citizens can escape a flutter of excitement at the prospects of a new, brighter and better Derry’. The second city’s second-class citizens did not need to take to the streets to get jobs and houses: they were already on the way.

Significance of Patricia McCloskey’s Dungannon campaign overstated

A close analysis of the archival material ultimately suggests a new chronology and a new context. The legend has it that the origins of the civil rights movement can be traced back to a 1963 campaign against Dungannon Urban District Council’s housing policies. Events in County Tyrone were important, but their significance has been overstated. Although census records show that proportionately more Catholics than Protestants lived in local authority housing, this does not mean that there was no discrimination in Northern Ireland. If the local Nationalist–Unionist electoral rivalry was a fierce one, as was the case in Dungannon, Catholics would only rarely be granted tenancies in Protestant wards. The young were the hardest hit: older Catholic families had benefited from slum clearance but younger ones had not been given a permanent home in over 30 years.

C. Desmond Greaves—his British-based Connolly Association had identified discrimination as Unionism’s weak spot as early as 1955. The civil rights movement has its origins in the political calculations of such activists rather than in the spontaneous actions of ordinary Northern Catholics. (Irish Democrat)

When politics rather than need again appeared to decide who would get tenancies in a just-completed estate, a group of young Catholic housewives led by Patricia McCloskey, a middle-aged doctor’s wife, ‘declared war’. Marches, pickets and occupations—all played out in the media spotlight—wrong-footed Unionists used to Nationalist calls for unification and pushed Stormont into promising 96 homes to the protesting families.

The housewives drew inspiration from the American civil rights movement, carrying placards with slogans such as ‘Racial Discrimination in Alabama Hits Dungannon’ and talking about staging their own version of the ‘March on Washington’. The momentum towards a movement was soon lost, however. The legend sidesteps this by skipping over the years to 1967. This telescoping of time gives the impression that acts of civil disobedience were building up steadily to the Derry march five years later. What happened instead was a wilful break with mass participation, direct action and American analogies—and no civil rights movement.

Patricia McCloskey used the prestige that the Dungannon protests had given her to set up the Campaign for Social Justice (CSJ). This was a pressure group that believed that if the ‘plain truth’ was presented to the British press, public and politicians, then Westminster would intervene to put right Unionist wrongs. The CSJ’s pamphlets were only in demand after the Troubles began, however; Fleet Street editors only sent journalists across the Irish Sea when there were disturbances to cover, and letters to ministers only yielded politely didactic replies explaining why they would remain aloof. The secretary of the CSJ’s British sister organisation, the Campaign for Democracy in Ulster, concluded that when it came to the problems of Northern Ireland ‘the mass of the British people know little and care less’.

C. Desmond Greaves and the Connolly Association

Years before the CSJ even wrote to a Labour politician, another group was getting promises from the party’s spokesman on Northern Irish affairs to hold a parliamentary debate on the question of civil liberties. The British-based Connolly Association had identified discrimination as Unionism’s weak spot as early as 1955. C. Desmond Greaves, the organisation’s chief and a veteran Communist, argued that Northern Ireland’s sectarian system kept the Protestant and Catholic working classes at each other’s throats. If full civil rights could be secured, then it followed that the workers would join together to oust the ‘Orange Tories’. Although Greaves was careful to point out that his plan did not ‘spell socialism’, he did admit that ‘its direction is as unmistakeable as Castro’s Cuba’.

Two members of the Connolly Association, Tony Coughlan and Roy Johnston, introduced these ideas into a Republican movement that had lost faith in physical force after the ’50s Border Campaign. In 1966 Coughlan published a paper that mapped out the road to an ‘All-Ireland Republic . . . in control of its own destiny’. A ‘broad’ movement that demanded ‘genuine democracy’ and used the ‘whole gamut of civil resistance’ would ‘enlighten’ the ‘Orange masses’. Meetings and seminars were held, a coalition was put together, and the Northern Ireland Civil Rights Association (NICRA) was launched in January 1967.

Eamonn McCann addressing a youthful audience outside Rossville flats, Derry—‘Our conscious, if unspoken, strategy was to provoke the police into overreaction and thus spark off mass reaction against the authorities’. (Eamon Melaugh)

Representatives of every political party may have helped to found NICRA, but Republicans and Communists made the running and made up almost all the executive committee. The civil rights campaign—if not the civil rights movement—has its origins in the political calculations of a few activists from Ireland and Britain instead of in the spontaneous actions of ordinary Northern Catholics.

Provocation worked

Around the world ’68 was not a fleeting festival of personal liberation but the climax of post-war radicalism. The attempts to salvage Marxism from the shipwreck of Soviet Communism, the campaigns for nuclear disarmament, the American civil rights movement, the interest in Third World guerrillas, student activism, the protests against the Vietnam War—all these processes permeated each other and flowed into ’68. The media and face-to-face contact allowed this adoption and adaptation of ideas to take place among different cultures and countries. There is consequently no point in insisting upon a strict separation of Martin Luther King’s marches from the May events in Paris. Both movements taught activists in Northern Ireland the same, simple, seminal lesson: provocation worked.

In an interview after the Selma march, King confessed that he had deliberately set out to provoke racist attacks. He knew that the media coverage would leave a deep impression about conditions in the South that would shock viewers and draw their sympathy. The star of the May events, Dany Cohn-Bendit, had an almost identical strategy: ‘Our daily “provocation” brought the latent authoritarianism of the bureaucracy into the open . . . dialogue gave way to the policeman’s baton [which] opened the eyes of many previously uncommitted students [and inspired them] to express their passive discontent.’

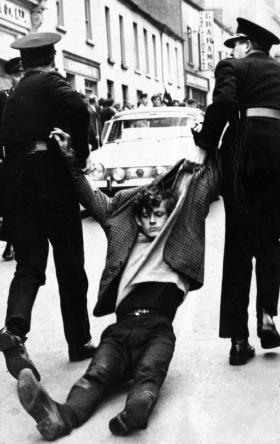

A protesting St Columb’s College student is dragged away by the RUC to Victoria Barracks on Strand Road on 5 October 1968.

NICRA did not learn the lesson. Its Communist chairwoman, Betty Sinclair, had admitted to Johnston as early as the summer of 1967 that NICRA was not doing ‘its job properly’. With ‘parliamentary questions and newspaper controversy’ having proved unsuccessful, NICRA finally took to the streets a year later. But the first civil rights march (Coalisland to Dungannon in August 1968) passed off peacefully—there was no provocation, no violence, no media interest, no public sympathy and no movement.

The tiny band of ’68ers had learnt the lesson. As the leading radical Eamonn McCann wrote in his memoirs, ‘our conscious, if unspoken, strategy was to provoke the police into overreaction and thus spark off mass reaction against the authorities’. When McCann came to organise a second civil rights march—a march through the Unionist shrine of Londonderry—this was what he set out to achieve. NICRA had no presence in the second city and was even warned by the local MP about ‘the company we were keeping’, yet it still took the foolhardy decision to sponsor McCann’s march.

On 5 October 1968, everything went to plan: stewarding was inadequate, the first rank of marchers was pushed up against the police line, missiles and abuse were hurled at the RUC, police officers hit out, and television cameras captured the violence on film. Only 400 or so people had taken part that day; when the march was restaged a month later, almost 40 times that number participated. Passive discontent had given way to active opposition and the civil rights movement had been born.

Simon Prince is a Junior Research Fellow in Modern British and Irish History at the University of Oxford.

Further reading:

C. Fink, P. Gassert and D. Junker (eds), 1968: the world transformed (Cambridge, 1998).

T. Hennessey, Northern Ireland: the origins of the Troubles (Dublin, 2005).

S. Prince, Northern Ireland’s ’68: civil rights, global revolt and the origins of the Troubles (Dublin, 2007).

B. Purdie, Politics in the streets: the origins of the Civil Rights Movement in Northern Ireland (Belfast, 1990).