John Redmond—forerunner of the Good Friday Agreement?

Published in 18th–19th - Century History, 20th-century / Contemporary History, Home Rule, Issue 2 (Mar/Apr 2007), News, Volume 15

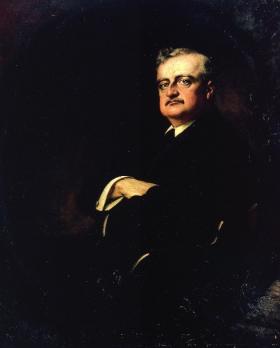

John Redmond by Henry Jones Thaddeus. (National Gallery of Ireland)

In 1956 John Redmond’s political opponent Eamon de Valera paid a generous tribute to him as ‘a great Wexfordman . . . who worked unselfishly for the welfare of this country’. On the same occasion (the centenary of Redmond’s birth) the then taoiseach, John A. Costello, spoke of him as ‘a leader of the Movement for National Advancement’. With the advantage of hindsight and a more calm, balanced and nuanced historical approach, we are better placed today to recognise his significance as an important figure in the long process that eventually led to Irish self-determination. Irish history is an intricate tapestry and we have more understanding now of the various threads, strands and patterns that go to make up that rich whole. We have a greater capacity to recognise the varied contribution made by different people to the evolution of Irish life and to acknowledge the brave people of different religions and political traditions who have made Ireland what it is. The collective amnesia about people, events, influences and achievements is beginning to be remedied.

I grew up and was educated in Wexford, and in those days John Redmond’s name was seldom mentioned. For many decades he did not feature prominently in public discourse or political commentary, nor was he officially recognised as an important figure in our country’s history. He seemed to have been largely forgotten and to have disappeared from the public square. Intriguingly, though, there was an underlying interest and continuing private memory. On the rare occasions when there were commemorative events, there was a real response and large attendances in Wexford at, for example, the centenary programme in 1956, the Wexford Historical Society seminar to mark the 75th anniversary of his death in 1993, and the 2005 Byrne/Perry Summer School. But generally he did not receive the public acknowledgement and credit he deserved. History, as we know, is written by the winners. Perhaps just as important as who writes the history is when it is written. I suspect that the historical judgement of today would be much kinder than that of, say, 40 years ago.

I am not a historian, and anyway space does not allow for a detailed historical analysis, but some things should be recalled here. Among the personal qualities admired during his lifetime were his oratorial, administrative and fund-raising skills; his search for consensus and his ability to build on the moderate middle ground; his loyalty, especially to Parnell; his pride in his native Wexford; and his religious faith and strong sense of family. Among his specific achievements were uniting the Irish Parliamentary Party (IPP) after the deep divisions of the 1890s and becoming party leader; playing a key role in the lead-up to the Wyndham Land Act of 1903, which represented a major change in Irish landholding; negotiating over a long period to achieve the establishment of the National University of Ireland in 1908; creating in Britain a greater awareness of Ireland’s needs, greater goodwill towards Ireland and more openness to political change; and achieving the balance of power for his party in Westminster in two general elections in 1910, thus securing the passage into law of the Home Rule Bill in 1914.

Enoch Powell, in his biography of Joseph Chamberlain, observed that ‘all political lives, unless they are cut off in mid-stream at a happy juncture, end in failure because that is the nature of politics and human affairs’. Sadly, Redmond was a striking example of this phenomenon. Against the background of the 1916 Rising and the progress of the Great War, the eclipse of the IPP and the decline in Redmond’s standing were rapid, dramatic and total. Just a few months after his death the IPP, which entered the 1918 general election with 80 seats, came out of it with just six. Redmond recognised that the movement and the methods to which he had given his life were doomed. In one of his last letters he foresaw ‘universal anarchy . . . when every blackguard who wants to commit an outrage will simply call himself a Sinn Féiner and thereby get the sympathy of the unthinking crowd’.

John Redmond (left) with his son William. (George Morrison)

Historians naturally explore the reasons for his decline and debate questions such as whether the IPP was too old and too tired; whether its focus was too narrow; whether Redmond’s centred belief in national unity and imperial unity and strength was naïve and unrealistic; and whether he failed to recognise important emerging trends and new thinking in Ireland. Yet over and above all these questions is the central fact that Redmond was extraordinarily unlucky. Nicholas Mansergh commented that Redmond preferred compromise at a time when compromise went out of Irish politics, and Diarmuid Ferritter has observed that Redmond was a parliamentarian when parliament was becoming increasingly irrelevant to what was happening on the ground. But Enoch Powell was only partly right. History does revisit and reassess events, personalities and trends, and reviews them within their context and from a longer perspective. There seems to be clear evidence of that sort of reassessment of John Redmond and a new interest in his life and times, his basic thinking and approach.

At the inauguration of her second term of office in November 2004, President McAleese said ‘we have struggled with that other ambition for the unity of our island, agreeing overwhelmingly to an honourable compromise in which we acknowledge the right of the people of Northern Ireland to decide their own destiny and declare our desire to work with them in peaceful partnership’. I suspect that John Redmond would be very comfortable with that fine sentiment; he wanted to move on and to look outwards. The development of the three sets of relationships—Unionist/Nationalist, British/Irish and North/South—that are at the heart of the Peace Process were ideals that Redmond worked for all his political life. In that sense he could well serve as a ‘patron’ of the Good Friday Agreement.

Walter Forde is chairman of the Byrne/Perry Summer School, Gorey, Co. Wexford.